“a new kind of coding”

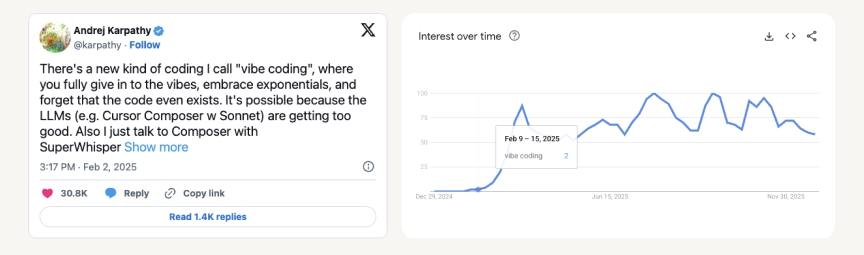

One year ago from today, Andrej Karpathy ↗ coined the term ‘vibe coding’— and in that short time, whole companies have lived and died off its promise of turning plain English into the world’s most popular programming language.

One year ago from today, Andrej Karpathy ↗ coined the term ‘vibe coding’— and in that short time, whole companies have lived and died off its promise of turning plain English into the world’s most popular programming language.

I first started using language models to write code in late 2023, back when Github Copilot began to take off. Copilot was more often wrong than right, but it was still enough to shave about a month off bencuan.me’s 2024 edition and save me hours of test-writing time at work.

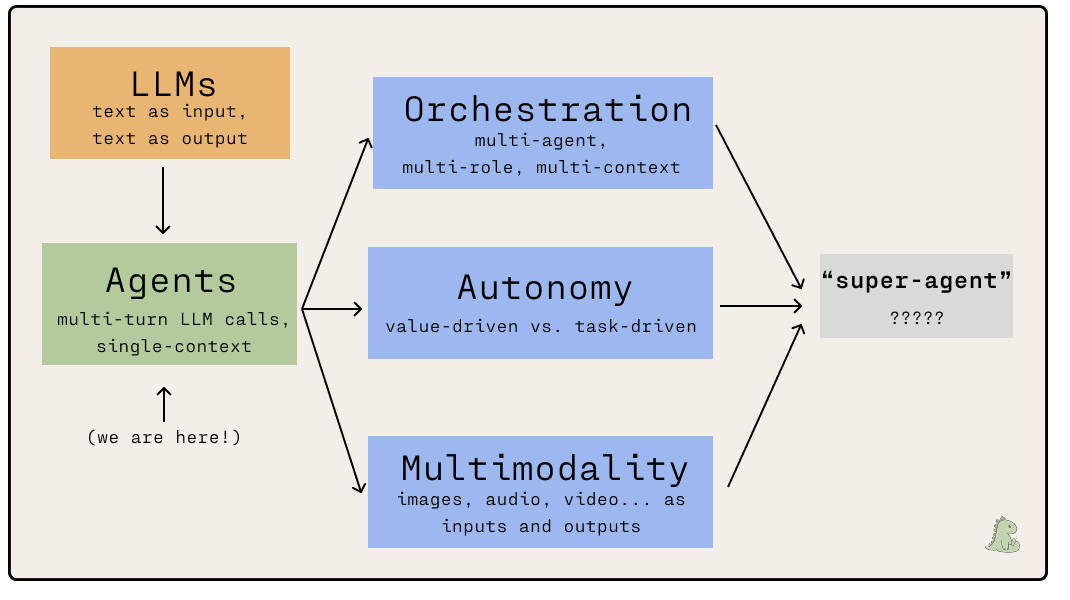

It’s only been very recently that LLM

“Vibe coding” seems to have broken containment from software engineering circles. It’s the Collins Dictionary 2025 word of the year ↗; there’s a New York Times article about it ↗; anecdotally, most of the folks who ask me “do you think AI will take over your job soon?” follow it up with some description of vibe coding. Naïvely, I think it’s generally a good thing that LLMs are democratizing software creation— I’d love it if more people could make more cool things!— But at the same time, vibe coding has become a convenient stand-in for slop generation, rising unemployment, the outsourcing of skilled thinking, and many other AI-targeted concerns.

One wonders at the atrophying of curiosity and problem-solving ability that will accompany widespread adoption of these tools. Do you really need an app to figure out if something will fit in your trunk? You are saving time at the expense of renouncing the thing that makes you human—your unique ability to think and solve problems.

—a comment on Kevin Roose’s NYT article ↗

While I don’t think LLMs will be taking over my job in the immediate future

In this post, I hope to capture the current state of code generation capability, in the specific context of my current understanding and usage of LLMs. I imagine both their capabilities and my reliance on them will continue rapidly increasing, and hope to offer a point of reference for advancements to come.

TL;DR

My goal from this post is to help me (and maybe you) learn more about coding agents, and make some informed decisions about how and what tools to use for the upcoming year.

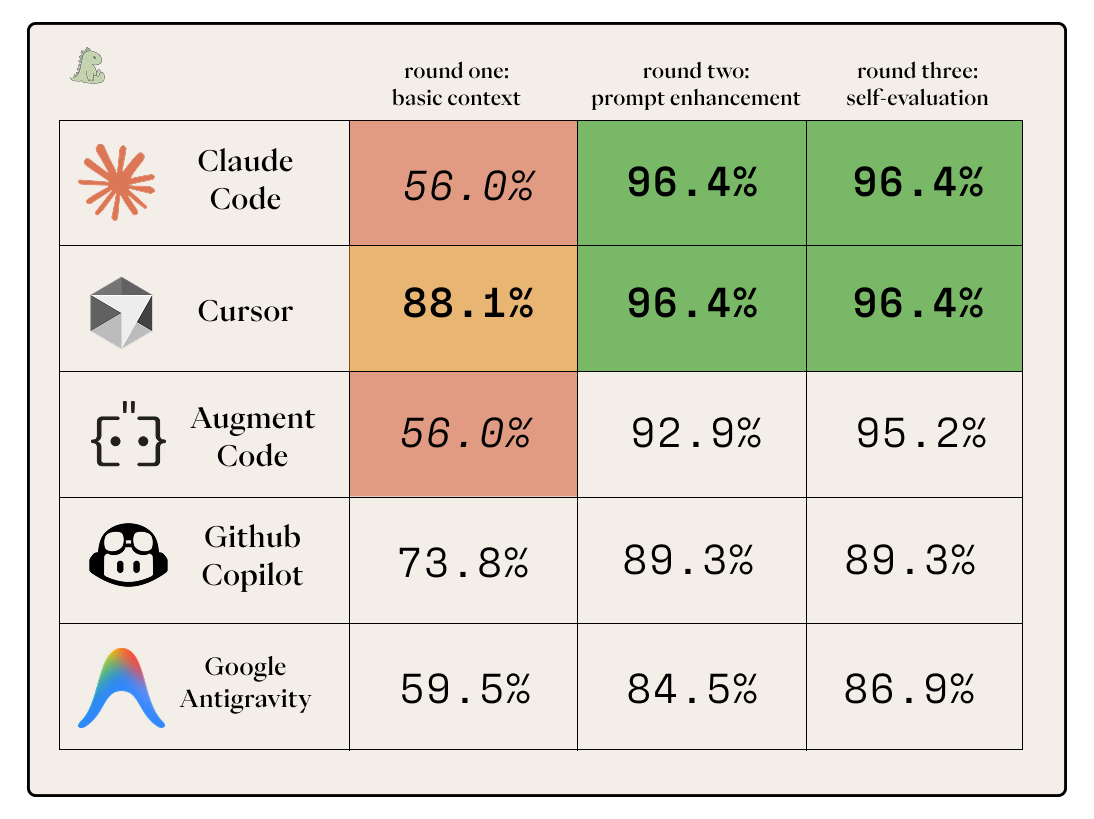

I evaluated 5 of the top platforms for agentic code generation as of January 2026: Claude Code, Github Copilot, Cursor, Google Antigravity, and Augment Code.

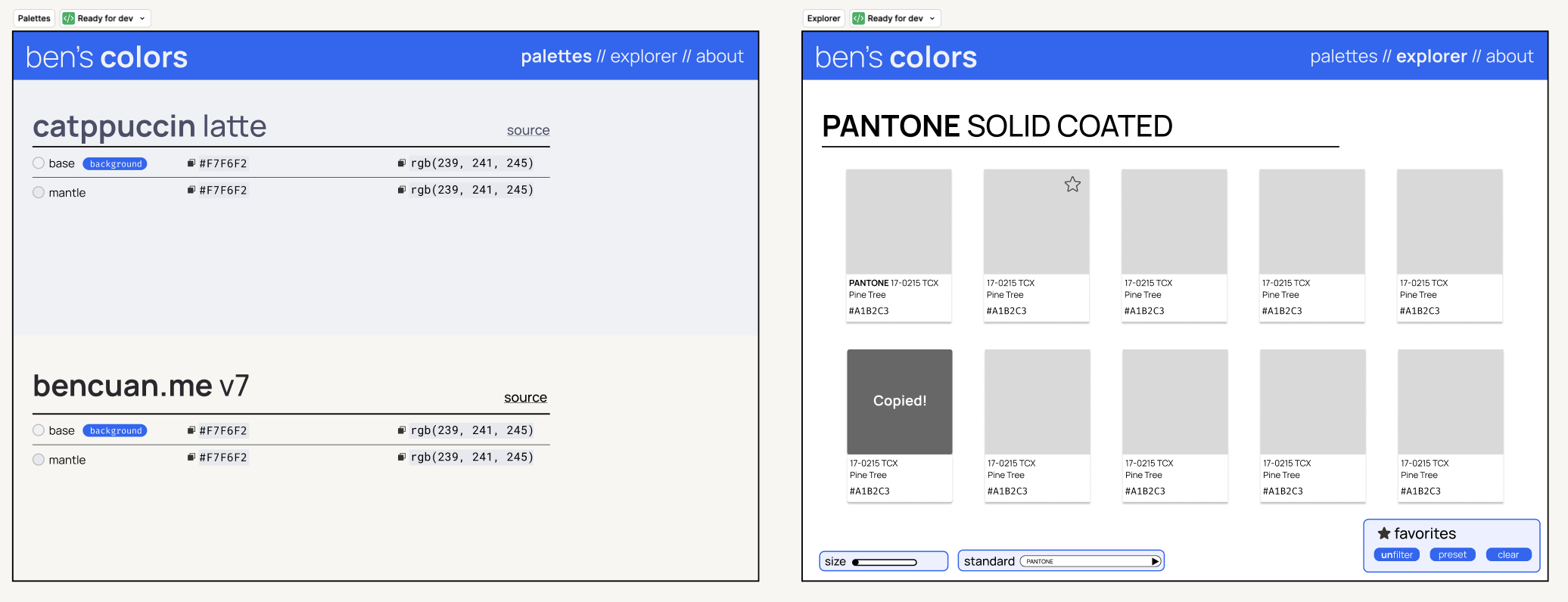

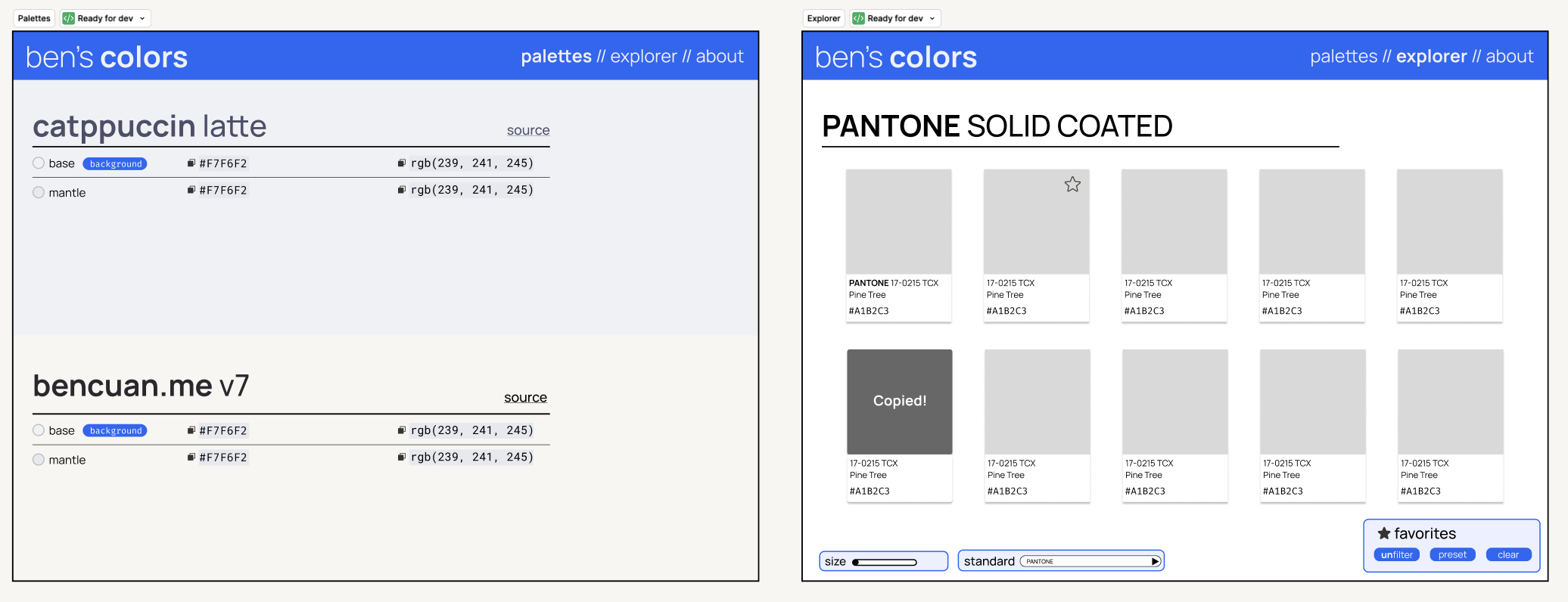

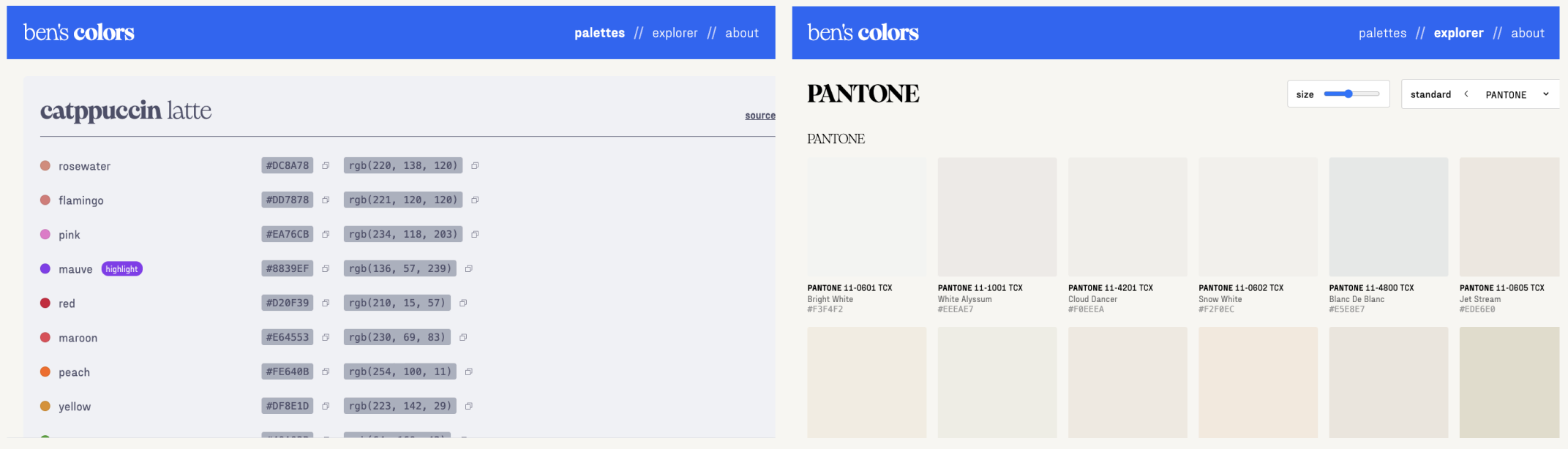

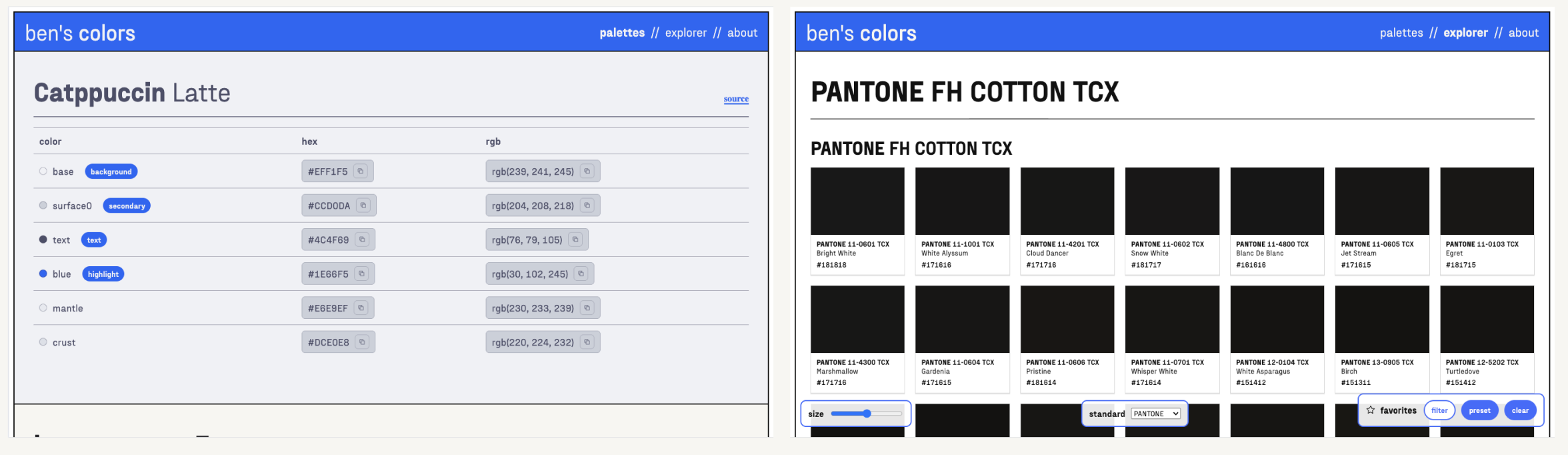

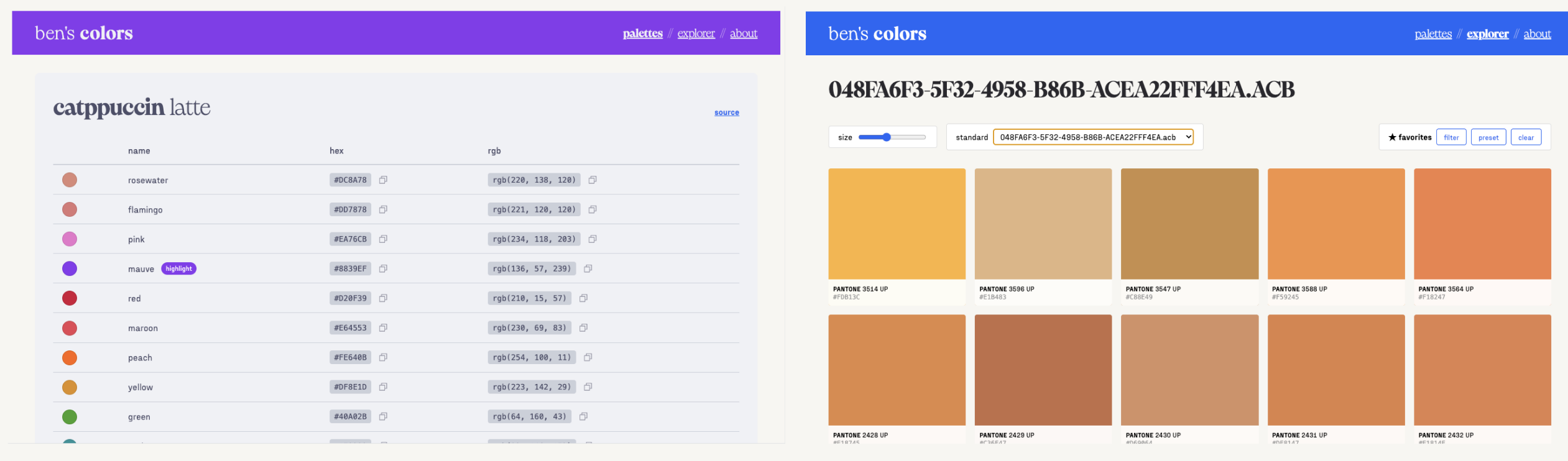

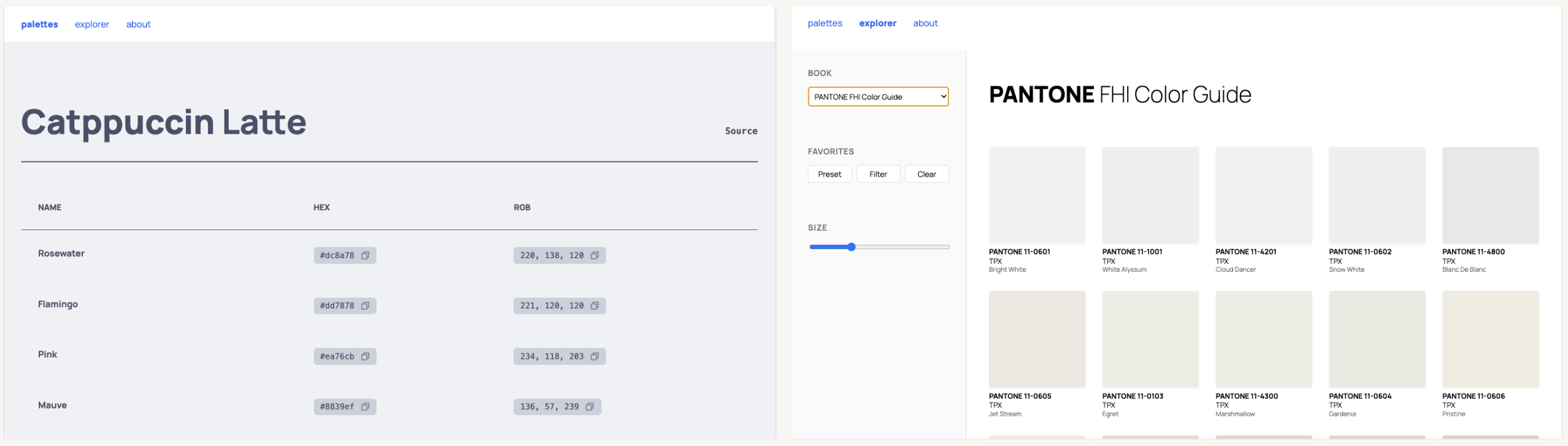

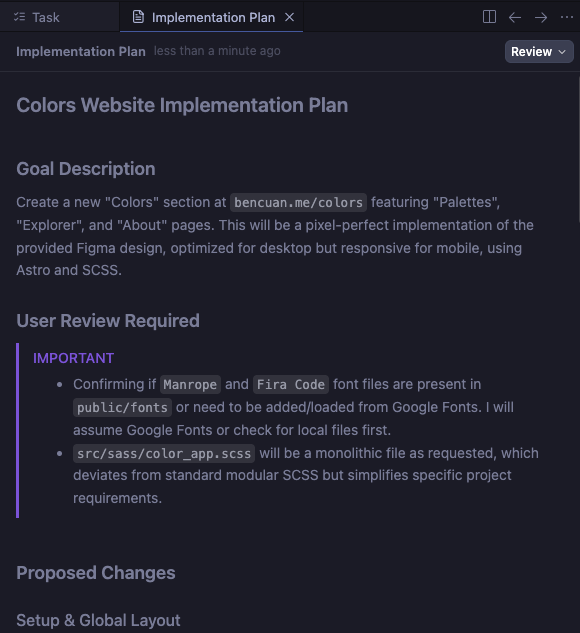

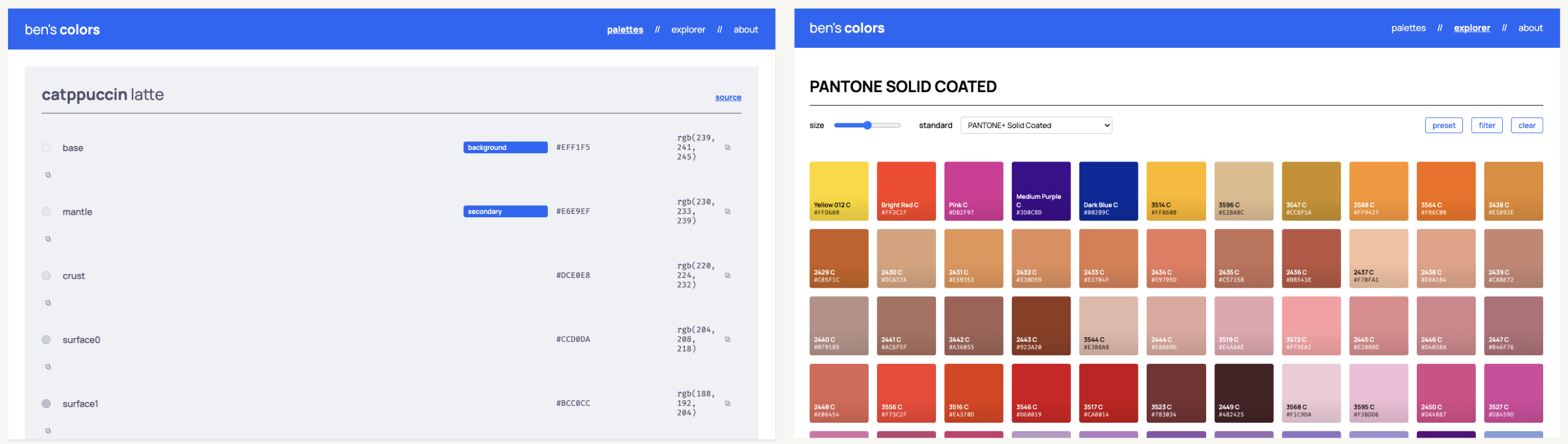

For this evaluation, I designed a simple web application in Figma (bencuan.me/colors) to organize my color palettes, and hand-wrote a prompt to create it in an existing codebase (this website). The original design looks like this:

I then prompted each of the 5 contenders to generate exactly that application in three rounds:

- In the first round, I provided the basic text prompt, the screenshot above, and MCP integrations to Figma and the Astro documentation (the SSG framework I use for my site).

- In the second round, I ran my original prompt through the prompt enhancement workflow suggested by each platform and re-ran code generation from the beginning.

- In the third round, I took the outputs from the second round and provided each agent an opportunity to evaluate its own work and correct any mistakes it identifies.

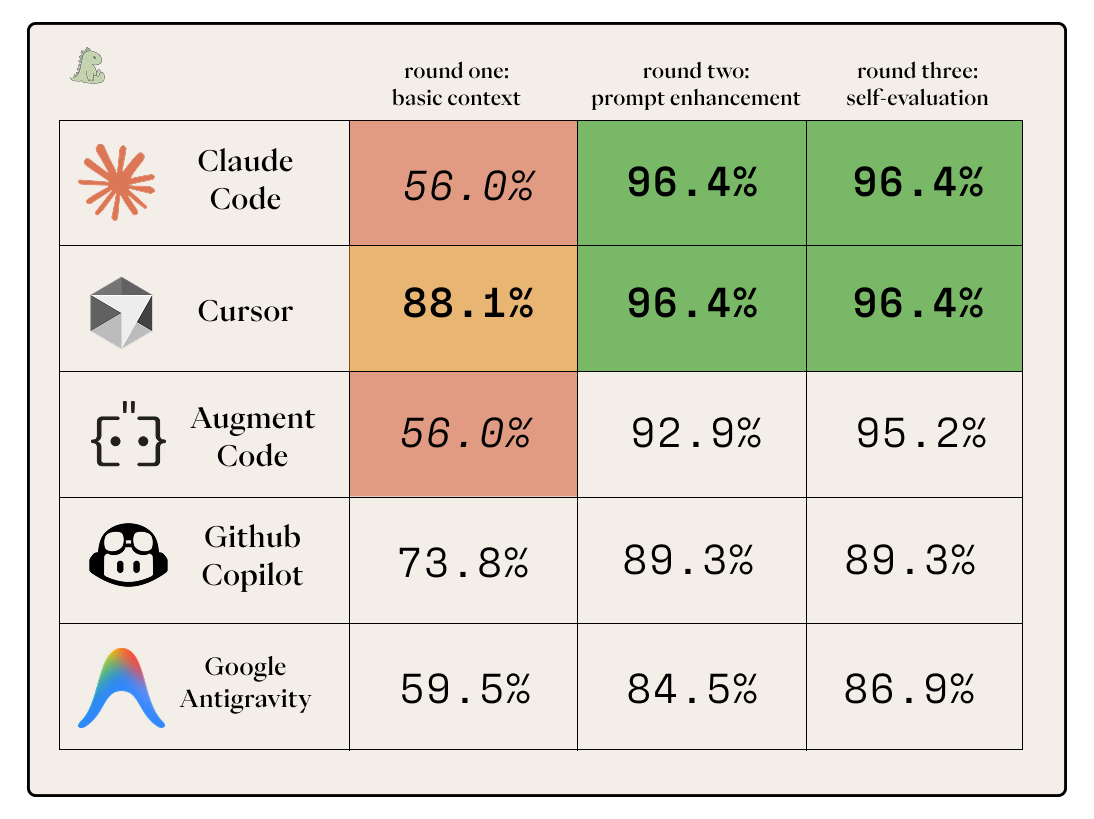

I evaluated each of the outputs on a list of criteria, where each point earned was one specific implementation detail I prompted the agent for. If an agent got all of them, I gave it a score of 100%.

My main findings

- Claude Opus 4.5 is the most effective model for code generation at the moment.

- I would currently recommend Claude Code with the prompt improver plugin ↗ as a go-to coding agent for most software engineers, and Cursor as a go-to coding agent for most non-engineers.

- The one-shot Figma-design-to-code-implementation workflow is currently useful but imperfect, and still requires significant prompt steering.

- Discounting model differences, agent capabilities of all five contenders appeared similar enough to be insignificant.

- Prompt enhancement is really important for Claude models, somewhat important for GPT-5.2, and not at all important for Gemini 3.

- Agents are currently very bad at evaluating their own performance.

Below is the summary for how well the agents did with respect to one another on the various tasks. If you want to know where all the numbers came from, read on!

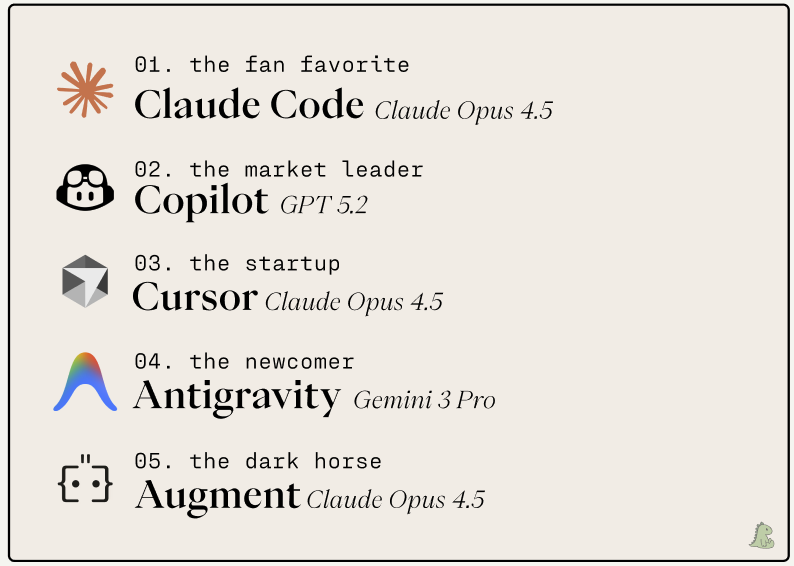

The Contenders

I chose the five agents above as a representation of what my researcher and engineer coworkers, friends, and acquaintances use and talk about. They’re roughly seeded purely on my uninformed pre-evaluation prediction on how well I think they will perform relative to each other, with some weighting on their popularity. (For example, my priors suggest Augment should beat Cursor, but I’m putting Cursor at a higher seed because it’s much more widely known.)

Most of the contenders use Claude Opus 4.5 under the hood as their default or ‘auto’ option. Opus 4.5 is widely considered the best model for code generation at time of writing; I intend to test this claim by evaluating Claude’s performance against GPT 5.2 and Gemini Pro 3 in the following configurations:

- I chose to use GPT 5.2 with Copilot because I wanted a representation of a “non-engineer vibe coder” who would opt to use the most well-known tool with the most well-known model.

- Antigravity is a Google-native offering and is optimized for use with Gemini, also by Google. Using other models is supported, but would defeat the purpose of including it in the evaluation.

Claude Code: The Fan Favorite

Like the Claude model itself, Claude Code has a cult following. It’s clear that the team working on this at Anthropic really, really cares, down to the smallest details (cute animations, live token counts, MCP integration as ‘skills’… it’s quite a charming product). On paper, this should be a winning formula— Claude Code combines the best interface with the best coding model.

Like the Claude model itself, Claude Code has a cult following. It’s clear that the team working on this at Anthropic really, really cares, down to the smallest details (cute animations, live token counts, MCP integration as ‘skills’… it’s quite a charming product). On paper, this should be a winning formula— Claude Code combines the best interface with the best coding model.

Claude Code’s interface is a clear stand-out compared to the rest, which are all variants of the same chat-sidebar formula. The interface also very clearly communicates stats (like time taken, number of tokens, and cost) during and after runs.

Form factor: CLI, installable via curl. Also available as a VSCode extension, and a desktop app that’s currently in public preview.

Cost: Choice of subscription ($20/month for Pro) or metered billing via API key. I chose to use metered billing, and this evaluation cost me $6.87 ($2.48 for round one, $2.89 for round two, and $1.50 for round three).

MCP Setup: claude mcp add --transport http astro-docs https://mcp.docs.astro.build/mcp and claude mcp add --transport http figma http://127.0.0.1:3845/mcp

Github Copilot: The Market Leader

Github Copilot has been around for a very long time (relatively speaking…) and is clearly ahead of the others in terms of market share at the moment. However, I find it interesting that very few people I know actively use it today. Is Copilot just a below-average product with great marketing, or can it justify itself as the market leader based on performance alone?

Form factor: VSCode extension. (Microsoft/GitHub is trying to market Copilot fairly heavily. I get spam popups telling me to install it semi-frequently, and it comes pre-installed to VSCode.)

Cost: Free for basic access, but agent use requires a paid plan. I paid for the $10/month Pro plan to get access to GPT 5.2 and cancelled it afterwards.

MCP Setup: Built-in VSCode MCP settings. I edited the JSON to the following:

{

"servers": {

"figma": {

"url": "http://127.0.0.1:3845/mcp",

"type": "http"

},

"astro docs": {

"url": "https://mcp.docs.astro.build/mcp",

"type": "http"

}

}

}

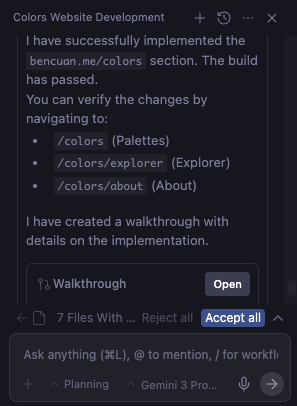

Cursor: The Startup

Cursor was one of the original generative code platforms available, and pioneered much of the UX we seem to have converged towards today. Their decision to maintain a VSCode fork as their primary interface was met with skepticism originally, but seems to be widely accepted now (and has since been copied by Windsurf, Antigravity, and others).

I’ve used Cursor a few times previously, but wasn’t impressed enough by its quality to switch to it more permanently. My general opinion of it pre-evaluation is “pretty UI with subpar outputs”. That being said, it’s still probably the second most popular agentic code platform at the moment (after Copilot) and is the best-positioned startup in the market.

Form factor: VSCode fork.

Cost: $20/month for Pro. I used a 7-day free trial for this evaluation and cancelled it afterwards.

MCP Setup: Ctrl+Shift+P -> View: Open MCP Settings, then paste in the JSON:

{

"mcpServers": {

"figma": {

"url": "http://127.0.0.1:3845/mcp",

"type": "http"

},

"astro-docs": {

"url": "https://mcp.docs.astro.build/mcp",

"type": "http"

}

}

}Google Antigravity: The Newcomer

Antigravity was first released to public preview on November 18th, just a bit over a month ago. According to Google’s release post ↗, the main purpose of Antigravity is to “be the home base for software development in the era of agents. Our vision is to ultimately enable anyone with an idea to experience liftoff and build that idea into reality.”

The not-so-subtle subtext: “From today, Google Antigravity is available in public preview at no charge, with generous rate limits on Gemini 3 Pro usage.” It’s obvious that Google is positioning Antigravity as a play to make Gemini more visible to developers, in hopes that it can begin to compete with Claude for engineering mindshare.

Antigravity is the spiritual successor of Windsurf ↗, which got HALO’ed out ↗ to Google for $2.4 billion and sold for parts to Cognition.

Does Gemini/Antigravity really deserve a spot at the table, or will Antigravity join Inbox and Google+ in the dead Google app graveyard ↗ soon? Let’s find out!

Form factor: VSCode fork.

Cost: The public preview is currently free with full access to all models, though I expect this to change soon. A Google AI subscription (starting at $20/month for Pro) extends rate limits significantly.

MCP Setup: cmd+shift+P -> MCP: Add server… -> paste in the IP addresses

- Figma local desktop:

http://127.0.0.1:3845/mcp - Astro documentation remote:

https://mcp.docs.astro.build/mcp

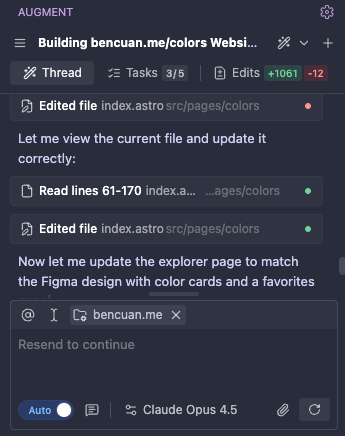

Augment: The Dark Horse

Augment is by far the least widely-known tool of the five contenders in this evaluation. I’ve been using it for much of the past year as my primary agent, both for work and personal use. This is mostly because I happen to have a lot of friends working on it!

I’m fairly confident that Augment was the best agent at some point in its existence (and places very highly on SWE-Bench), but whether that is still the case today remains to be seen.

Augment’s main selling point is its context engine, which works really well in large codebases. I don’t consider my website to be a “large codebase” by any means, but will throw it in anyways because I’m curious if another contender’s performance will convince me to switch away from it.

Form factor: VSCode extension, also available via CLI and some other editors (vim, cursor…)

Cost: $20/month for Indie. I’m currently grandfathered into a $30/month “legacy developer” plan, which is basically their $60/month Standard subscription at a steep discount for being there early.

MCP Setup: Augment Extension -> Settings -> Import MCP from JSON -> paste in Figma and Astro one at a time

"figma": {

"url": "http://127.0.0.1:3845/mcp",

"type": "http"

}"astro-docs": {

"url": "https://mcp.docs.astro.build/mcp",

"type": "http"

}Notable Omissions

Windsurf: Given that the top talent at Windsurf got acquihired by Google to go work for Antigravity, I’m not optimistic on Windsurf staying around much longer in its current form.

Devin: Cognition’s “AI software engineer” made a massive splash when it first debuted in 2024, much ahead of its time. It’s getting very close to delivering on its original vision. It’s not the right tool for this evaluation, however— I’m not looking to simulate an entire software engineering workflow (with Linear tickets and PR submissions and reviews…); I’m just looking to generate some code as an individual user.

Cline: Currently the most popular open source, bring-your-own-key agent. I’m omitting this because I’d choose to use it with Opus 4.5 anyways, and I don’t see any reason I would use it over Claude Code (which is also open-source) for this specific evaluation.

Codex: OpenAI released the latest GPT-5.2-Codex model on December 18; it’s only available via the first-party Codex agent for now. Even though this is technically OpenAI’s state-of-the-art at evaluation time, it’s not different enough from Copilot with 5.2 non-codex to justify adding a sixth entry. Models come out nearly every week— new releases are becoming less and less noteworthy. (and, it’s most definitely coming to Copilot in the coming weeks).

Gemini CLI: Google’s direct Claude Code competitor. I felt like it was redundant to evaluate both Gemini CLI and Antigravity, and chose the more interesting of the two.

The Task

This post began as a rabbit-hole inside of a rabbit-hole. I’d originally set out to redesign my TurtleNet series so I could re-post it on my website, but was unhappy with my color selections. I’d had some success in the past by limiting myself to only using colors from known standards (like Pantone), and wanted to make a quick little app to organize the various colors I was playing around with.

After a couple iterations on Augment and being rather unhappy with the outputs I was getting, I wondered if I could turn this into an experiment to see what I could do to get the best possible vibe-coded application.

I chose to evaluate this specific task for several reasons:

- It’s pretty representative of an average workload I would prompt an LLM in a one-shot manner for: it’s moderately complex, builds on top of a moderately large existing codebase, and leans towards specific instruction-following but with some room for decision-making.

- It’s almost entirely self-contained, and is therefore reproducible in the future (given the same prompt, design file, and starting state of the bencuan.me repository).

- Given its frontend-y nature, there’s a reasonable amount of objective criteria to evaluate an agent’s performance on that isn’t explicitly unit-testable.

3 I’m looking for agents to fetch/transform well-known color palette data from provided links and datasets, look up documentation, parse Figma designs, and to follow very specific instructions about what interactions to implement.

Design

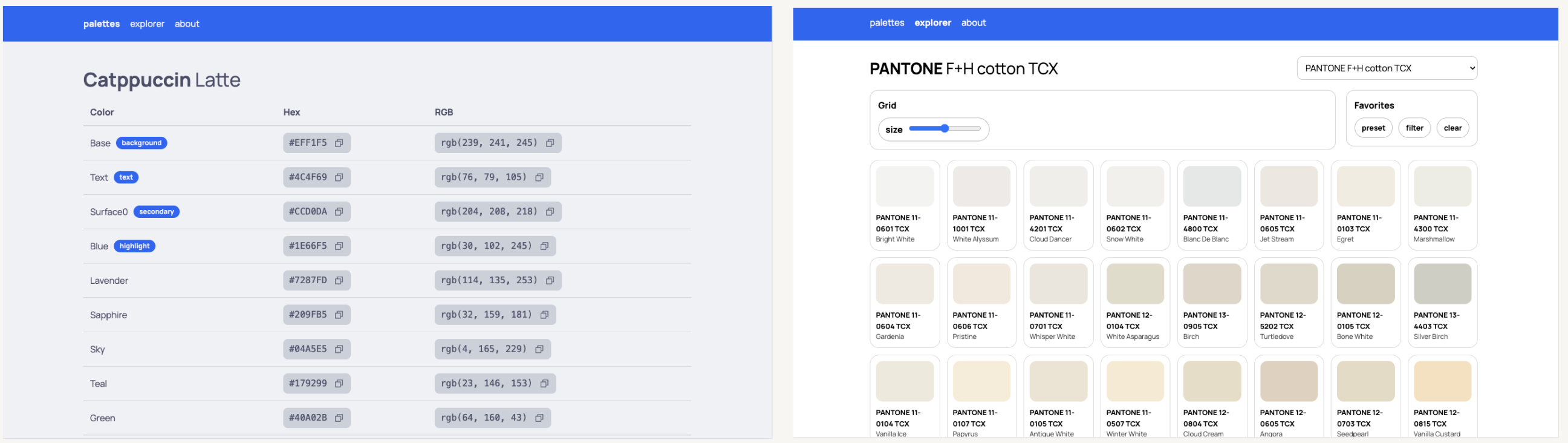

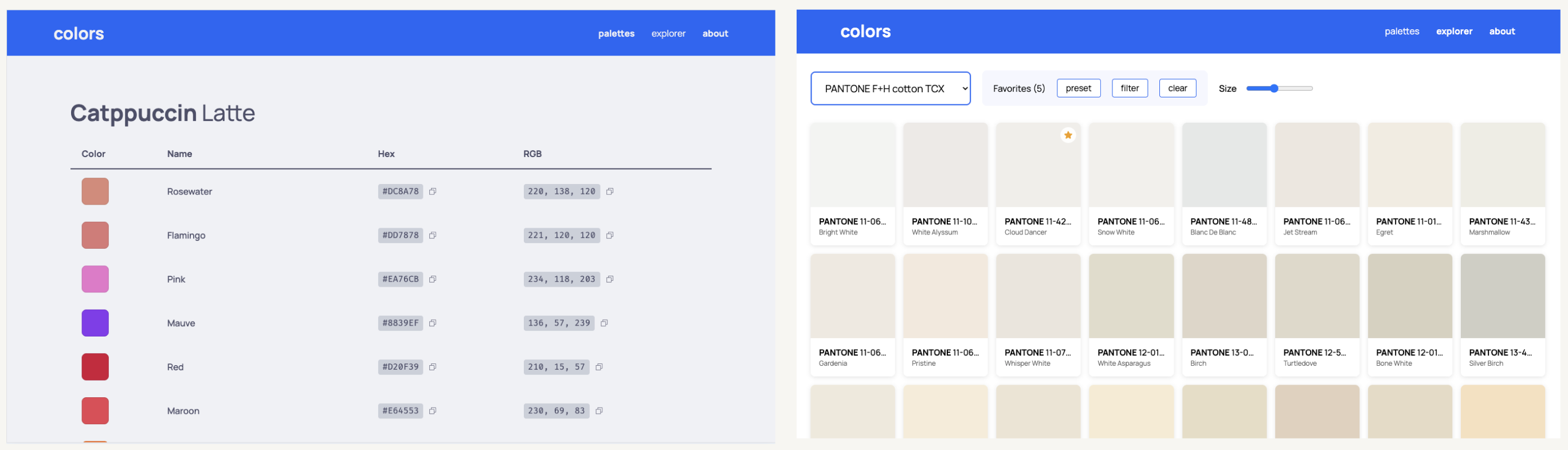

I hastily put together a basic design in Figma (without LLM assistance), which I’ve attached a couple times above already. You can view the original Figma file here ↗.

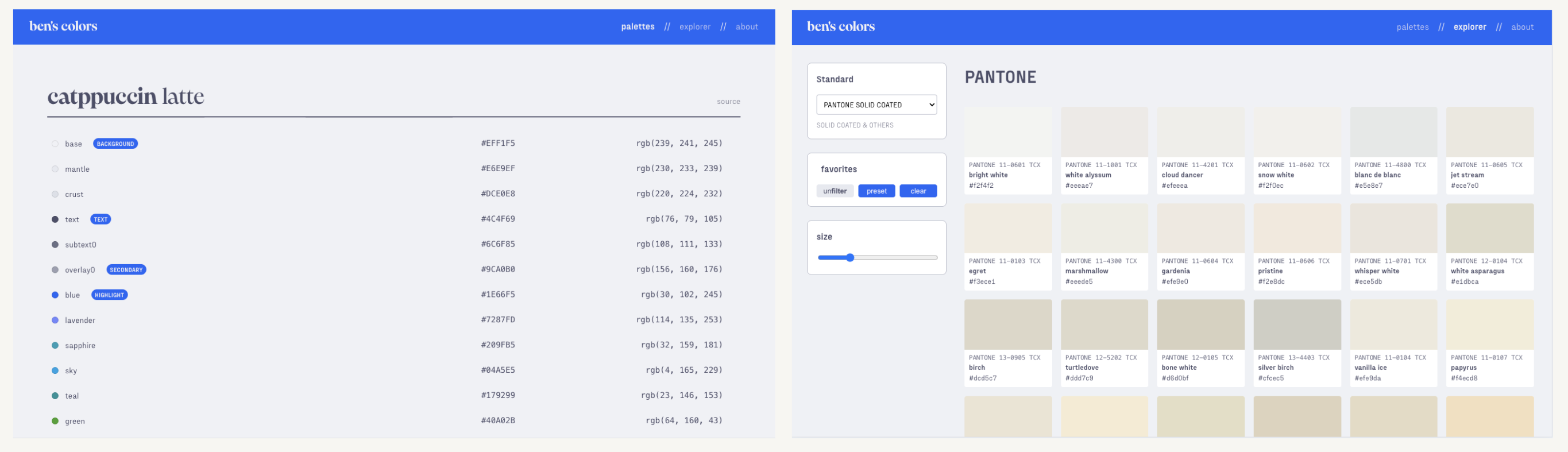

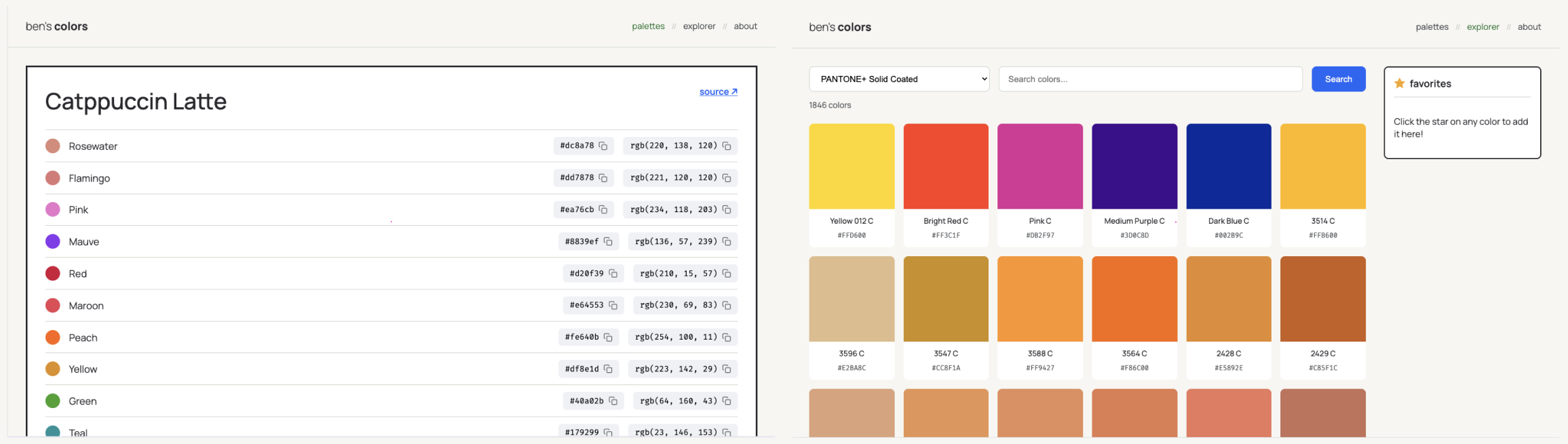

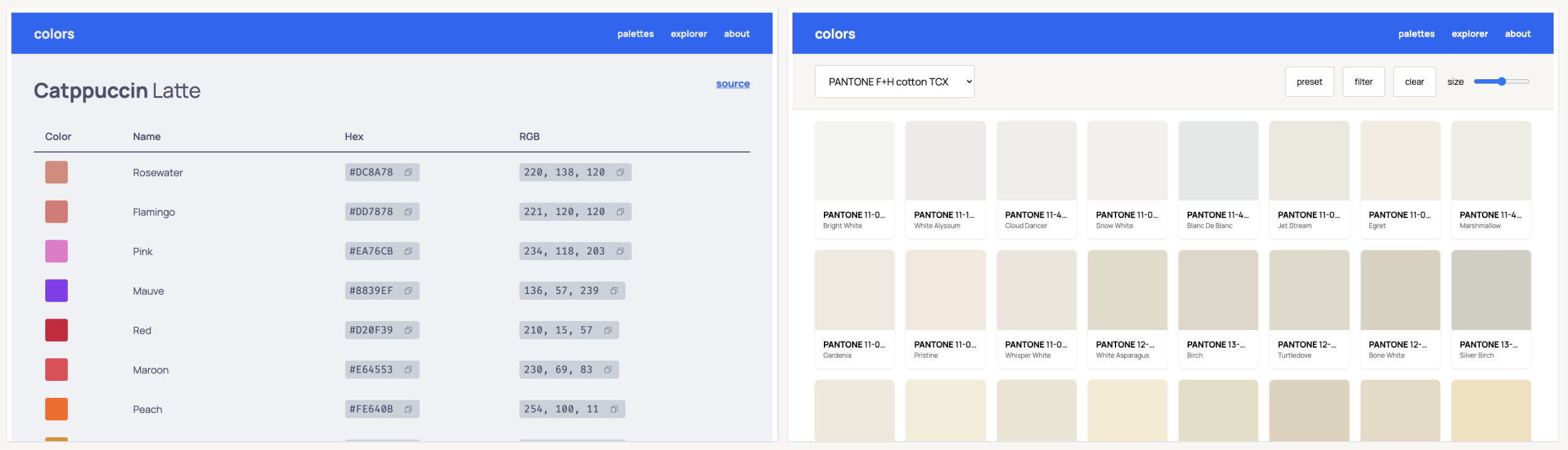

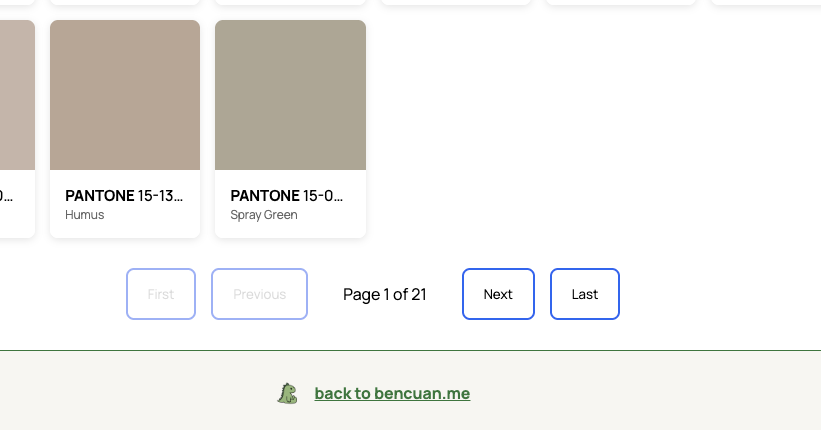

I created three simple pages:

- The first page collects all the color palettes I’ve created or used in the past. They’re all hard-coded tables, so this should be relatively easy to create.

- The second page is a color explorer, seeded with some old color books I found in this repo ↗. It has some basic controls, like a system to save favorites I come across, or a slider to change the size of the swatches for closer inspection. (I know the point of color standards is generally for color matching rather than discovery, but this does seem to help me a lot for some reason!).

- The third page (not pictured below) is a super simple ‘about’ page with some text explaining what the website is and why I made it (i.e. for this evaluation!).

Prompt writing

Over the last few months, I’m finding my prompts to be getting more and more elaborate. I’m very much not a “make me a cool app” kind of LLM user; rather, I tend to abuse my fast typing speed and info-dump as much implementation detail as possible into a giant mess of a prompt. I quite enjoy the process of creating prompts— it forces me to turn my thoughts into coherent words, and helps me clarify what exactly I’m looking for before I ask for it.

You can see the full, original prompt below. All of the text in that box was written manually by myself, without any assistance from LLMs.

Below is the exact prompt I copy-pasted into each agent for Round One:

I want to create a new website at bencuan.me/colors based on the “color” Figma project (which can be accessed via the Figma MCP integration).

General guidelines:

- The default color for the header is Catppuccin Latte blue, hex 1E66F5.

- Links are also in Catppuccin Latte blue and are bolded and underlined.

- The current page (palettes/explorer/about) should be bolded in the header. If a non-current page link is hovered it should also be bolded (with some animation time; the font is variable).

- Every page should have a footer with background hex F7F6F2, a top border color 297638 of 1px width, and a centered link of color 297638 that says “back to bencuan.me” and links to https://bencuan.me. An image of Kevin the Dinosaur (favicon.png) should be displayed on the left side of the link. An example of the footer can be found in the “About” page on Figma: @https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=4-207&m=dev ↗

- This design is optimized for desktop use, but ensure that minimal mobile styling is introduced so the page doesn’t look completely broken on smaller devices.

Code guidelines:

- Keep all styles in a separate color_app.scss. This should be a standalone sass file that only inherits fonts, mixins and spacing, and define all of its own styles, animations, etc. in one big file for all of the colors pages. (It is okay to define new fonts in

_fonts.scss) - Keep all code as separate from existing code as possible. If any new content or components are needed, put them in a

color-appsubfolder. - Use Astro best practices and idiomatics whenever possible. Use the “Astro docs” MCP server to access the Astro documentation.

- Treat Figma design details (like spacing, font sizes, and other formatting) as suggestions but not the ultimate truth, but use the exact text contents of the header, interactive components, and about page. If there are obvious developer errors like grid spacing being a few pixels off, or elements that seem out of place, use your best judgement to balance code conciseness and simplicity with what is presented by Figma. If any decision points arise, make the decision and note it down in a DECISIONS.md file.

- Keep comments and documentation as minimal as possible. I prefer code to be concise and readable on its own.

First, implement the “palettes” page. @https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=1-2&m=dev ↗

- The palettes are read from

color-books/_palettes.json. Help fill this JSON file in with these exact three sample palettes for the time being: Catppuccin Latte (https://catppuccin.com/palette/ ↗), bencuan.me v7 (https://bencuan.me/colophon/), and Dracula (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dracula_(color_scheme) ↗, in that order. Some colors will have a tag, which will appear in the pill next to the color name if exists. Valid tags are “background”, “secondary”, “text”, and “highlight”. Assign exactly one color to each type of tag in each palette based on your best judgement. - When a user scrolls to a certain color palette, update the header to have the highlight color as the background, and the background color as the text color. (This is intentionally inverted to create contrast.)

- The color palette section itself should reflect its own colors. For example, all text should be in the ‘text’ color, the tag pill background should be in the ‘highlight’ color, the hex/rgb code background should be in the ‘secondary’ color, and the background should be in the ‘background’ color.

- When the user hovers over a row in the table, change that row’s background color to the secondary color.

- Use the Phosphor icon for ‘copy’, and have that display as a button next to both the hex and RGB codes in the markdown table for each palette. When clicked, copy the respective color code to the clipboard and temporarily change the icon to a check mark.

- Fill in the source links with the links provided above (except for Dracula, whose source link is https://draculatheme.com/ ↗). The source link should be aligned with the end of the Markdown table.

- Bold the first word of each theme name in the title.

- Ensure the final theme in the list is tall enough so the user can experience the header change.

Second, implement the “explorer” page. @https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=2-33&m=dev ↗

- All color books are available in JSON format under

src/color-books. The “components” are in CIELAB format, so we will need a helper function to convert them into hex and RGB values as needed. - A JSON containing friendly names for certain PANTONE colors is available in

_pantone-color-names.json. These names will need to be formatted in a friendly manner. For example, “PANTONE 13-5305 TCX” should display “Pale Aqua” in the second line of the swatch. If no friendly name can be matched, then the second line of the swatch should be blank. - Bold the prefix (like “PANTONE” or “HKS”) in both the main header title and in the swatch main name first line. All color books with the same prefix should be rendered on the same page, and each have a distinct title. Special cases: Pantone and Pantone+ should be on the same page as each other, and TOYO 94 and TOYO COLOR FINDER should be on the same page as each other.

- The “standard” selector can be used to jump between pages.

- On mobile devices, hide the favorites and size popups. Only display the standard selector.

- When a swatch is selected, play an animation that rounds and unrounds the border radius, darken the square, display “Copied!” on top of the color square, and copy the hex code to the clipboard. It should also update the header to use that color, inferring light/dark text in the header depending on how light the color is.

- If a swatch is hovered, it should be scaled up a bit, and the Phosphor star outline icon should display on the top right. If the star is clicked, the color should be added to favorites.

- Store favorites to localStorage so if a user refreshes the page the favorites remain.

- The “preset” button in the favorites panel should automatically override the currently selected favorites and load a preset of favorites. This should be read from a

_favorites.jsonin the color-books directory, which contains a list of color names per standard prefix. The “notes” field is unused in code and is only for human readability. - The “filter” button in the favorites panel should hide all colors except for the user-selected favorites, then read “unfilter” where “un” is bolded.

- The “clear” button in the favorites panel should clear all favorites and reset the header colors.

- The “size” slider should be ratcheting and control how many swatches will appear on the grid.

Finally, implement the “about” page. @https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=4-207&m=dev ↗

- The about page is very straightforward, static, and has no interaction other than links.

- “This repository” links to https://github.com/jacobbubu/acb ↗

- “here” links to https://github.com/64bitpandas/bencuan.me/tree/main/src/color-books ↗

- “Catppuccin blue” links to https://catppuccin.com/ ↗

- “Click here” links back to bencuan.me root

- “State of Vibe Coding evaluation” links to https://bencuan.me/blog/vibe25

- Replace “INSERT YOUR NAME HERE” with your name

Context

In addition to the text prompt, I’m providing agents with a few additional resources with some minimal guidance about how to use them.

- I provide the exact screenshot of the two side-by-side pages you just saw in the ‘design’ section as an image attachment.

- I provide a local MCP server from the Figma Desktop application (set up with this guide ↗ ) so agents can have direct access to the original design.

- I provide a remote MCP server to

https://mcp.docs.astro.build/mcpso the agent can read up on how Astro works in hopes that it can follow along with the existing code more effectively.

Setup

I cloned a fresh copy of bencuan.me at the commit c05d833949a1ade05bfd908bdf9cefb075e4a3c4, making sure that all submodules (i.e. just the fonts directory) are initialized. You can browse or download the exact starting files here ↗.

Next, I set up the two MCP servers (Figma and Astro Docs) within each platform.

Then, I pasted the screenshot of the design and the prompt into the agent box and pressed enter.

After the completion of the turn, I ran yarn dev and navigated to localhost:4321/colors, then displayed it on both a 1366x768 size window and a IPhone SE size window (using Chrome Dev Tools) to manually evaluate it against the rubric. (See Scoring below.)

Scoring

I’ve manually curated a list of acceptance criteria I’m looking for below. Each point is equally weighted. A score is assigned based on the fraction of criteria that are met to the number of all criteria.

For example, a score of 100% means that the agent completed every task, and that the site looks and functions exactly how I envisioned it to function. A score of 50% means exactly half of the tasks were completed.

Notably, I am not scoring on cost, runtime, or ease of use. All of the contenders were cheap / quick / usable enough to make these non-issues for me.

I’ve attached the rubric below. It’s not perfect, but at least it provides some sort of objective reference point.

Total: 42 possible points.

Really Basic Stuff

3 possible points. Did the agent:

- make sure the website could be built/served without errors?

- not do anything really stupid (like try to run

rm rf /)? - finish the turn on its own (didn’t need to be manually stopped for any reason)?

General Criteria

13 possible points. Did the agent:

- make only critical changes to existing files?

- avoid making unnecessary imports/references to external packages?

- organize Sass stylesheets as specified (with the correct imports to the existing fonts/mixins/spacing files)?

- find and use the correct fonts (Manrope and Fira Code)?

- define the Manrope font-face in

_fonts.scssas specified? - create a DECISIONS.md file as specified?

- create a reusable header component?

- create a reusable footer component?

- use the correct styles and text for the header component and links?

- use the correct styles and text for the footer component and links?

- keep comments/documentation minimal as specified?

- use Astro patterns and best practices?

- make specific mobile-only styles to allow the app to function on mobile devices?

Palettes Page

9 possible points. Did the agent:

- create a table for each theme?

- find and create the exact 3 themes in

_palettes.jsonas specified in the prompt? - select the correct theme names and bold the first word?

- assign the correct source links to each of the themes?

- assign and display the correct primary, secondary, highlight, and text colors for each theme?

- make the table rows change color when hovered?

- create a functioning copy button next to each color code that copies the code to the clipboard and turns into a checkmark when clicked?

- make the header change colors as the user scrolls between sections?

- make the last section tall enough to allow triggering the header change?

Explorer Page

14 possible points. Did the agent:

- load all of the correct data from the provided color books?

- create a working CIELAB-to-hex conversion utility and display the correct colors+hex codes?

- display the correct friendly Pantone names from

_pantone-color-names.json? - create a functioning click-to-copy that has the desired styling?

- create a functioning size slider?

- create a functioning ‘standard’ selector that switches between color standards?

- load colors with reasonable performance (i.e., not render every single color in preload)?

- create a functioning favorite button that can be selected/deselected on each swatch?

- create a functioning favorites filter that only shows the selected favorites?

- create a functioning ‘unfilter’ button that replaces the ‘filter’ button and shows all colors when clicked?

- create a functioning preset loader that reads and applies the configuration in

_favorites.json? - create a functioning ‘clear’ button that removes all favorites?

- save favorites to localStorage?

- make the header change color when a color is clicked?

About Page

3 possible points. Did the agent:

- use the exact text from the Figma file, replacing INSERT YOUR NAME HERE with the agent’s name?

- fill in the correct links?

- format the text and links as requested?

Round One: Basic Multimodal Context

tokens all the way down!

In this first round, I give each agent the starting prompt and context, and let it rip! Whenever they finish the turn and tell me they’re done, I begin the evaluation.

The purpose of this round is to evaluate one-shot code generation performance. This is how I believe the typical vibe coder uses these tools.

Claude Code

Score: 56.0% (23.5/42)

Unfortunately, the Explorer page was unusable and crashed the browser shortly after loading, so Claude Code gets a low score for this round.

- I’m unsure whether any of the functionality in the explorer page actually works, since it’s not testable.

- The formatting was off for smaller screens (you can observe that the content appears to be cut off, even on a 1366x768 size screen).

- The Palettes page was nearly perfect, other than there being a white border around the content and the header color change not working properly when scrolling back up to the first theme.

- Claude ignored the Manrope font entirely, using a mixture of Eiko and Fraktion.

Really Basic Stuff

Did the agent:

- make sure the website could be built/served without errors?

- not do anything really stupid (like try to run

rm rf /)? - finish the turn on its own (didn’t need to be manually stopped for any reason)?

General Criteria

Did the agent:

- make only critical changes to existing files?

- avoid making unnecessary imports/references to external packages?

- organize Sass stylesheets as specified (with the correct imports to the existing fonts/mixins/spacing files)?

- find and use the correct fonts (Manrope and Fira Code)?

- define the Manrope font-face in

_fonts.scssas specified? - create a DECISIONS.md file as specified?

- create a reusable header component?

- create a reusable footer component?

- use the correct styles and text for the header component and links?

- use the correct styles and text for the footer component and links?

- keep comments/documentation minimal as specified?

- use Astro patterns and best practices?

- make specific mobile-only styles to allow the app to function on mobile devices? - 0pts, somewhat broken on smaller displays.

Palettes Page

Did the agent:

- create a table for each theme?

- find and create the exact 3 themes in

_palettes.jsonas specified in the prompt? - select the correct theme names and bold the first word?

- assign the correct source links to each of the themes?

- assign and display the correct primary, secondary, highlight, and text colors for each theme?

- make the table rows change color when hovered?

- create a functioning copy button next to each color code that copies the code to the clipboard and turns into a checkmark when clicked?

- [/] make the header change colors as the user scrolls between sections? 0.5 pts, doesn’t work on the first theme.

- make the last section tall enough to allow triggering the header change?

Explorer Page

Did the agent:

- load all of the correct data from the provided color books?

- create a working CIELAB-to-hex conversion utility and display the correct colors+hex codes?

- display the correct friendly Pantone names from

_pantone-color-names.json? - create a functioning click-to-copy that has the desired styling?

- create a functioning size slider?

- create a functioning ‘standard’ selector that switches between color standards?

- load colors with reasonable performance (i.e., not render every single color in preload)?

- create a functioning favorite button that can be selected/deselected on each swatch?

- create a functioning favorites filter that only shows the selected favorites?

- create a functioning ‘unfilter’ button that replaces the ‘filter’ button and shows all colors when clicked?

- create a functioning preset loader that reads and applies the configuration in

_favorites.json? - create a functioning ‘clear’ button that removes all favorites?

- save favorites to localStorage?

- make the header change color when a color is clicked?

About Page

Did the agent:

- use the exact text from the Figma file, replacing INSERT YOUR NAME HERE with the agent’s name?

- fill in the correct links?

- format the text and links as requested?

Copilot

Score: 73.8% (31/42)

Copilot followed the design most accurately out of all the contenders.

- Maybe too accurately- I put black borders around the frame for human-legibility, but Copilot decided they were a core part of the design. DECISIONS.md noted that it relied heavily on the screenshots and pretty much ignored Figma altogether, which could explain this behavior.

- Copilot seemed to really, really like Fraktion Sans for some reason, and made every text element use that font. I don’t recall ever giving it that instruction, but hey, at least it looks nice…

- Copilot took by far the longest (almost an hour), asking me if I wanted to keep going halfway through because it timed out.

- Copilot was the only agent to get the color conversion incorrect. All of the colors appear much darker than they should.

- I couldn’t find any way to select favorites.

- Rendering the Pantone page crashes the browser because there are too many swatches.

- Copilot made the number of columns scale based on screen size, which I thought was a neat touch!

Really Basic Stuff

Did the agent:

- make sure the website could be built/served without errors?

- not do anything really stupid (like try to run

rm rf /)? - [/] finish the turn on its own (didn’t need to be manually stopped for any reason)? - took long enough that it prompted me to continue. 0.5 points.

General Criteria

Did the agent:

- make only critical changes to existing files?

- avoid making unnecessary imports/references to external packages?

- organize Sass stylesheets as specified (with the correct imports to the existing fonts/mixins/spacing files)?

- find and use the correct fonts (Manrope and Fira Code)?

- define the Manrope font-face in

_fonts.scssas specified? - create a DECISIONS.md file as specified?

- create a reusable header component?

- create a reusable footer component?

- use the correct styles and text for the header component and links?

- use the correct styles and text for the footer component and links?

- keep comments/documentation minimal as specified?

- use Astro patterns and best practices?

- make specific mobile-only styles to allow the app to function on mobile devices?

Palettes Page

Did the agent:

- create a table for each theme?

- find and create the exact 3 themes in

_palettes.jsonas specified in the prompt? - select the correct theme names and bold the first word?

- assign the correct source links to each of the themes?

- assign and display the correct primary, secondary, highlight, and text colors for each theme?

- make the table rows change color when hovered?

- create a functioning copy button next to each color code that copies the code to the clipboard and turns into a checkmark when clicked?

- [/] make the header change colors as the user scrolls between sections? - 0.5 points. Technically works but extremely finnicky.

- make the last section tall enough to allow triggering the header change?

Explorer Page

Did the agent:

- load all of the correct data from the provided color books?

- create a working CIELAB-to-hex conversion utility and display the correct colors+hex codes? - 0 pts. incorrect

- display the correct friendly Pantone names from

_pantone-color-names.json? - create a functioning click-to-copy that has the desired styling?

- create a functioning size slider?

- create a functioning ‘standard’ selector that switches between color standards?

- load colors with reasonable performance (i.e., not render every single color in preload)? - 0 pts. crashes on larger sets like PANTONE.

- create a functioning favorite button that can be selected/deselected on each swatch?

- create a functioning favorites filter that only shows the selected favorites?

- create a functioning ‘unfilter’ button that replaces the ‘filter’ button and shows all colors when clicked?

- create a functioning preset loader that reads and applies the configuration in

_favorites.json? - create a functioning ‘clear’ button that removes all favorites?

- save favorites to localStorage?

- make the header change color when a color is clicked?

About Page

Did the agent:

- use the exact text from the Figma file, replacing INSERT YOUR NAME HERE with the agent’s name?

- fill in the correct links?

- format the text and links as requested?

Cursor

Score: 88.1% (37/42)

Surprisingly, this was the best submission of Round One! I’m starting to see why Cursor is so popular amongst non-engineers who want to try vibe coding.

- Perfect palettes page, 9 out of 9!!

- Best Explorer page by far. Most things work, and colors load performantly. Cursor put each color book in its own section.

- Jumbled up the color book names, unsure what happened there but the colors themselves look fine.

Really Basic Stuff

Did the agent:

- make sure the website could be built/served without errors?

- not do anything really stupid (like try to run

rm rf /)? - finish the turn on its own (didn’t need to be manually stopped for any reason)?

General Criteria

Did the agent:

- make only critical changes to existing files?

- avoid making unnecessary imports/references to external packages?

- organize Sass stylesheets as specified (with the correct imports to the existing fonts/mixins/spacing files)?

- find and use the correct fonts (Manrope and Fira Code)?

- define the Manrope font-face in

_fonts.scssas specified? - create a DECISIONS.md file as specified?

- create a reusable header component?

- create a reusable footer component?

- use the correct styles and text for the header component and links?

- use the correct styles and text for the footer component and links?

- keep comments/documentation minimal as specified?

- use Astro patterns and best practices?

- [/] make specific mobile-only styles to allow the app to function on mobile devices? - 0.5pts, technically works but looks a bit broken on mobile.

Palettes Page

Did the agent:

- create a table for each theme?

- find and create the exact 3 themes in

_palettes.jsonas specified in the prompt? - select the correct theme names and bold the first word?

- assign the correct source links to each of the themes?

- assign and display the correct primary, secondary, highlight, and text colors for each theme?

- make the table rows change color when hovered?

- create a functioning copy button next to each color code that copies the code to the clipboard and turns into a checkmark when clicked?

- make the header change colors as the user scrolls between sections?

- make the last section tall enough to allow triggering the header change?

Explorer Page

Did the agent:

- load all of the correct data from the provided color books?

- create a working CIELAB-to-hex conversion utility and display the correct colors+hex codes?

- display the correct friendly Pantone names from

_pantone-color-names.json? - [/] create a functioning click-to-copy that has the desired styling? - 0.5pts, it works but the animation is super janky.

- create a functioning size slider?

- create a functioning ‘standard’ selector that switches between color standards?

- load colors with reasonable performance (i.e., not render every single color in preload)?

- create a functioning favorite button that can be selected/deselected on each swatch?

- create a functioning favorites filter that only shows the selected favorites?

- create a functioning ‘unfilter’ button that replaces the ‘filter’ button and shows all colors when clicked?

- create a functioning preset loader that reads and applies the configuration in

_favorites.json? - 0pts, presets did not work. - create a functioning ‘clear’ button that removes all favorites?

- save favorites to localStorage?

- make the header change color when a color is clicked?

About Page

Did the agent:

- use the exact text from the Figma file, replacing INSERT YOUR NAME HERE with the agent’s name?

- fill in the correct links?

- format the text and links as requested?

Antigravity

Score: 59.5% (25/42)

Antigravity was by far the fastest agent, and completed the task in under five minutes! This was really impressive to me, but the output quality itself was rather middling.

- Added the

colorddependency— this was unnecessary and Antigravity was the only agent to add an external dependency. - Pantone colors are slow, but load eventually.

- Uses query parameters (

/explorer?std=HKS) instead of putting each standard on its own page. - None of the Explorer functionality seemed to work for me, but it did adhere extremely well to the original theme.

Really Basic Stuff

Did the agent:

- make sure the website could be built/served without errors?

- not do anything really stupid (like try to run

rm rf /)? - finish the turn on its own (didn’t need to be manually stopped for any reason)?

General Criteria

Did the agent:

- make only critical changes to existing files?

- avoid making unnecessary imports/references to external packages?

- organize Sass stylesheets as specified (with the correct imports to the existing fonts/mixins/spacing files)?

- find and use the correct fonts (Manrope and Fira Code)?

- define the Manrope font-face in

_fonts.scssas specified? - create a DECISIONS.md file as specified?

- create a reusable header component?

- create a reusable footer component?

- use the correct styles and text for the header component and links?

- use the correct styles and text for the footer component and links?

- keep comments/documentation minimal as specified?

- use Astro patterns and best practices?

- make specific mobile-only styles to allow the app to function on mobile devices? - 0pts, super broken on mobile

Palettes Page

Did the agent:

- create a table for each theme?

- find and create the exact 3 themes in

_palettes.jsonas specified in the prompt? - select the correct theme names and bold the first word?

- assign the correct source links to each of the themes?

- assign and display the correct primary, secondary, highlight, and text colors for each theme?

- make the table rows change color when hovered?

- create a functioning copy button next to each color code that copies the code to the clipboard and turns into a checkmark when clicked? - 0pts, no copy button found.

- make the header change colors as the user scrolls between sections?

- make the last section tall enough to allow triggering the header change?

Explorer Page

Did the agent:

- load all of the correct data from the provided color books?

- create a working CIELAB-to-hex conversion utility and display the correct colors+hex codes?

- display the correct friendly Pantone names from

_pantone-color-names.json? - create a functioning click-to-copy that has the desired styling?

- create a functioning size slider?

- create a functioning ‘standard’ selector that switches between color standards?

- load colors with reasonable performance (i.e., not render every single color in preload)?

- create a functioning favorite button that can be selected/deselected on each swatch?

- create a functioning favorites filter that only shows the selected favorites?

- create a functioning ‘unfilter’ button that replaces the ‘filter’ button and shows all colors when clicked?

- create a functioning preset loader that reads and applies the configuration in

_favorites.json? - create a functioning ‘clear’ button that removes all favorites?

- save favorites to localStorage?

- make the header change color when a color is clicked?

About Page

Did the agent:

- use the exact text from the Figma file, replacing INSERT YOUR NAME HERE with the agent’s name?

- fill in the correct links?

- format the text and links as requested?

Augment

Score: 56.0% (23.5/42)

Augment really freestyled here and completely disregarded my design in a lot of ways.

Augment really freestyled here and completely disregarded my design in a lot of ways.

- Augment was the only agent that couldn’t complete on its own (discounting the Copilot forced-user-interaction). It hung at around the 20-minute mark, and I stopped it at 30 minutes.

- Strictly code-wise, Augment produced the cleanest and most performant output, but this was largely overshadowed by the fact that not much of what I asked for was actually present.

Really Basic Stuff

Did the agent:

- make sure the website could be built/served without errors?

- not do anything really stupid (like try to run

rm rf /)? - finish the turn on its own (didn’t need to be manually stopped for any reason)? - 0pts, had to be stopped manually.

General Criteria

Did the agent:

- make only critical changes to existing files?

- avoid making unnecessary imports/references to external packages?

- organize Sass stylesheets as specified (with the correct imports to the existing fonts/mixins/spacing files)?

- find and use the correct fonts (Manrope and Fira Code)?

- define the Manrope font-face in

_fonts.scssas specified? - create a DECISIONS.md file as specified? - 0pts, no decisions file.

- create a reusable header component?

- create a reusable footer component?

- use the correct styles and text for the header component and links?

- use the correct styles and text for the footer component and links?

- keep comments/documentation minimal as specified?

- use Astro patterns and best practices?

- make specific mobile-only styles to allow the app to function on mobile devices?

Palettes Page

Did the agent:

- create a table for each theme?

- find and create the exact 3 themes in

_palettes.jsonas specified in the prompt? - [/] select the correct theme names and bold the first word? - 0.5pts, no bolding.

- assign the correct source links to each of the themes?

- assign and display the correct primary, secondary, highlight, and text colors for each theme?

- make the table rows change color when hovered?

- create a functioning copy button next to each color code that copies the code to the clipboard and turns into a checkmark when clicked?

- make the header change colors as the user scrolls between sections?

- make the last section tall enough to allow triggering the header change?

Explorer Page

Did the agent:

- load all of the correct data from the provided color books? - unsure, the standard selector is broken.

- create a working CIELAB-to-hex conversion utility and display the correct colors+hex codes?

- display the correct friendly Pantone names from

_pantone-color-names.json? - create a functioning click-to-copy that has the desired styling?

- create a functioning size slider?

- create a functioning ‘standard’ selector that switches between color standards?

- load colors with reasonable performance (i.e., not render every single color in preload)?

- create a functioning favorite button that can be selected/deselected on each swatch?

- create a functioning favorites filter that only shows the selected favorites?

- create a functioning ‘unfilter’ button that replaces the ‘filter’ button and shows all colors when clicked? - technically passes; the favorites panel has a deselector that works.

- create a functioning preset loader that reads and applies the configuration in

_favorites.json? - create a functioning ‘clear’ button that removes all favorites?

- save favorites to localStorage?

- make the header change color when a color is clicked?

About Page

Did the agent:

- use the exact text from the Figma file, replacing INSERT YOUR NAME HERE with the agent’s name?

- fill in the correct links? - did not use the correct links.

- format the text and links as requested?

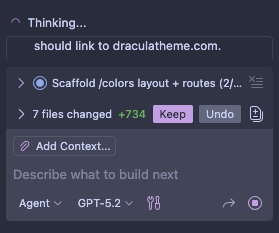

Round Two: Prompt Enhancement

work it harder, make it better!

The purpose of this round is to evaluate the effectiveness of prompt enhancement.

After ChatGPT started taking off, people realized that asking it to “think harder” actually worked really well! This quickly formalized into chain-of-thought prompting ↗, which is the foundation for most “thinking” and “reasoning” models as of today.

Gemini Pro 3, Claude Opus 4.5, and GPT 5.2 are all considered within this class of reasoning model, and perform the best if they’re given clear instructions on what steps they need to begin generating chain-of-thought. This example from Anthropic’s prompt improvement documentation ↗ illustrates this rather well— it shows how a basic initial prompt like this:

From the following list of Wikipedia article titles, identify which article this sentence came from. Respond with just the article title and nothing else. Article titles: {{titles}} Sentence to classify: {{sentence}}gets expanded into this prompt, which much more clearly states the order in which the LLM should proceed with thinking and output generation:

You are an intelligent text classification system specialized in matching sentences to Wikipedia article titles. Your task is to identify which Wikipedia article a given sentence most likely belongs to, based on a provided list of article titles.

First, review the following list of Wikipedia article titles:

<article_titles>

{{titles}}

</article_titles>

Now, consider this sentence that needs to be classified:

<sentence_to_classify>

{{sentence}}

</sentence_to_classify>

Your goal is to determine which article title from the provided list best matches the given sentence. Follow these steps:

1. List the key concepts from the sentence

2. Compare each key concept with the article titles

3. Rank the top 3 most relevant titles and explain why they are relevant

4. Select the most appropriate article title that best encompasses or relates to the sentence's content

Wrap your analysis in <analysis> tags. Include the following:

- List of key concepts from the sentence

- Comparison of each key concept with the article titles

- Ranking of top 3 most relevant titles with explanations

- Your final choice and reasoning

After your analysis, provide your final answer: the single most appropriate Wikipedia article title from the list.

Output only the chosen article title, without any additional text or explanation.In theory, prompt improvement should be at least provide a marginal improvement. But how well does it work, exactly?

In this round, I intend to give each agent the best possible scenario for it to one-shot an application perfectly to my original specifications.

- I first do an iteration of manual prompt improvement, filling in some details that were missing in the original prompt and caused LLMs to generate code I wasn’t looking for. (Expand the ‘Modified Prompt’ below if you want to see what I changed— I left the structure the same and didn’t delete old instructions.)

- Then, I used the prompt improvement guidelines supplied by each agent, if it exists. (The only agent that I couldn’t find any official guidelines for was Cursor, so I just used Claude’s built-in prompt improver instead.)

Changelog:

- Explicitly specify I want Manrope and Fira Code fonts.

- Specify the exact text for the ‘about’ section.

- Tell the agent to render each font book separately due to performance.

- Specify that the backgrounds for the palettes section should fill up 100% of the screen width.

- Specify “Ensure the first theme color appears again if the user scrolls all the way to the top of the page.”

- Specify that the entire swatch, not just the color square, should get slightly rounded when clicked.

- Direct agents to ensure good performance when rendering color swatches.

I want to create a new website at bencuan.me/colors based on the “color” Figma project (which can be accessed via the Figma MCP integration).

General guidelines:

- The default color for the header is Catppuccin Latte blue, hex 1E66F5.

- The fonts used are Manrope (sans-serif font for most elements) and Fira Code (monospace for codes).

- Links are also in Catppuccin Latte blue and are bolded and underlined.

- The current page (palettes/explorer/about) should be bolded in the header. If a non-current page link is hovered it should also be bolded (with some animation time; the font is variable).

- Every page should have a footer with background hex F7F6F2, a top border color 297638 of 1px width, and a centered link of color 297638 that says “back to bencuan.me” and links to https://bencuan.me. An image of Kevin the Dinosaur (favicon.png) should be displayed on the left side of the link. An example of the footer can be found in the “About” page on Figma: @https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=4-207&m=dev ↗

- This design is optimized for desktop use, but ensure that minimal mobile styling is introduced so the page doesn’t look completely broken on smaller devices.

Code guidelines:

- Keep all styles in a separate color_app.scss. This should be a standalone sass file that only inherits fonts, mixins and spacing, and define all of its own styles, animations, etc. in one big file for all of the colors pages. (It is okay to define new fonts in

_fonts.scss) - Keep all code as separate from existing code as possible. If any new content or components are needed, put them in a

color-appsubfolder. - Use Astro best practices and idiomatics whenever possible. Use the “Astro docs” MCP server to access the Astro documentation.

- Treat Figma design details (like spacing, font sizes, and other formatting) as suggestions but not the ultimate truth, but use the exact text contents of the header, interactive components, and about page. If there are obvious developer errors like grid spacing being a few pixels off, or elements that seem out of place, use your best judgement to balance code conciseness and simplicity with what is presented by Figma. If any decision points arise, make the decision and note it down in a DECISIONS.md file.

- Keep comments and documentation as minimal as possible. I prefer code to be concise and readable on its own.

First, implement the “palettes” page. @https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=1-2&m=dev ↗

- The palettes are read from

color-books/_palettes.json. Help fill this JSON file in with these exact three sample palettes for the time being: Catppuccin Latte (https://catppuccin.com/palette/ ↗), bencuan.me v7 (https://bencuan.me/colophon/), and Dracula (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dracula_(color_scheme) ↗, in that order. Some colors will have a tag, which will appear in the pill next to the color name if exists. Valid tags are “background”, “secondary”, “text”, and “highlight”. Assign exactly one color to each type of tag in each palette based on your best judgement. - When a user scrolls to a certain color palette, update the header to have the highlight color as the background, and the background color as the text color. (This is intentionally inverted to create contrast.)

- The color palette section itself should reflect its own colors. For example, all text should be in the ‘text’ color, the tag pill background should be in the ‘highlight’ color, the hex/rgb code background should be in the ‘secondary’ color, and the background should be in the ‘background’ color.

- When the user hovers over a row in the table, change that row’s background color to the secondary color.

- Use the phosophor icon for ‘copy’, and have that display as a button next to both the hex and RGB codes in the markdown table for each palette. When clicked, copy the respective color code to the clipboard and temporarily change the icon to a check mark.

- Fill in the source links with the links provided above (except for Dracula, whose source link is https://draculatheme.com/ ↗). The source link should be aligned with the end of the Markdown table.

- Bold the first word of each theme name in the title.

- Ensure the final theme in the list is tall enough so the user can experience the header change.

- Ensure the first theme color appears again if the user scrolls all the way to the top of the page.

- the backgrounds for the palettes section should fill up 100% of the screen width.

Second, implement the “explorer” page. @https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=2-33&m=dev ↗

- All color books are available in JSON format under

src/color-books. The “components” are in CIELAB format, so we will need a helper function to convert them into hex and RGB values as needed. - A JSON containing friendly names for certain PANTONE colors is available in

_pantone-color-names.json. These names will need to be formatted in a friendly manner. For example, “PANTONE 13-5305 TCX” should display “Pale Aqua” in the second line of the swatch. If no friendly name can be matched, then the second line of the swatch should be blank. - The default-selected color book should be the Pantone TCX book that has the friendly names specified in pantone-color-names.json.

- Bold the prefix (like “PANTONE” or “HKS”) in both the main header title and in the swatch main name first line. Separate each color book into its own page and ensure that the “standard” selector can be used to jump between pages.

- Ensure good performance and lazy-load color swatches whenever possible, since color books can be thousands of entries long.

- On mobile devices, hide the favorites and size popups. Only display the standard selector.

- When a swatch is selected, play an animation that slightly rounds and unrounds the border radius of the entire swatch, darken the square, display “Copied!” on top of the color square, and copy the hex code to the clipboard. It should also update the header to use that color, inferring light/dark text in the header depending on how light the color is.

- If a swatch is hovered, it should be scaled up a bit, and the Phosphor star outline icon should display on the top right. If the star is clicked, the

- Store favorites to localStorage so if a user refreshes the page the favorites remain.

- The “preset” button in the favorites panel should automatically override the currently selected favorites and load a preset of favorites. This should be read from a

_favorites.jsonin the color-books directory, which contains a list of color names per standard prefix. The “notes” field is unused in code and is only for human readability. - The “filter” button in the favorites panel should hide all colors except for the user-selected favorites, then read “unfilter” where “un” is bolded.

- The “clear” button in the favorites panel should clear all favorites and reset the header colors.

- The “size” slider should be ratcheting and control how many swatches will appear on the grid.

Finally, implement the “about” page. @https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=4-207&m=dev ↗

- The about page is very straightforward, static, and has no interaction other than links. It contains the exact text:

I made this page to keep track of all the color palettes I’ve created or have enjoyed using. I’ve found myself flipping through hundreds of tabs for color matching inspiration; I hope that this site can help me (and maybe you) reduce the clutter a bit!

This page was generated with <INSERT YOUR NAME HERE> for my State of Vibe Coding evaluation in December 2025. If you’re reading this, you’re looking at the winning submission! Congrats to <INSERT YOUR NAME HERE> :)

The Explorer was seeded with color books from this repository. View the source code here if you’d like to access these colors in JSON format.

This page is typeset in Manrope and fira code. Its default accent color is Catppuccin blue.- “This repository” links to https://github.com/jacobbubu/acb ↗

- “here” links to https://github.com/64bitpandas/bencuan.me/tree/main/src/color-books ↗

- “Catppuccin blue” links to https://catppuccin.com/ ↗

- “Click here” links back to bencuan.me root

- “State of Vibe Coding evaluation” links to https://bencuan.me/blog/vibe25

- Replace “INSERT YOUR NAME HERE” with your name

- Bold “Manrope” and “fira code” and typeset them in their respective font.

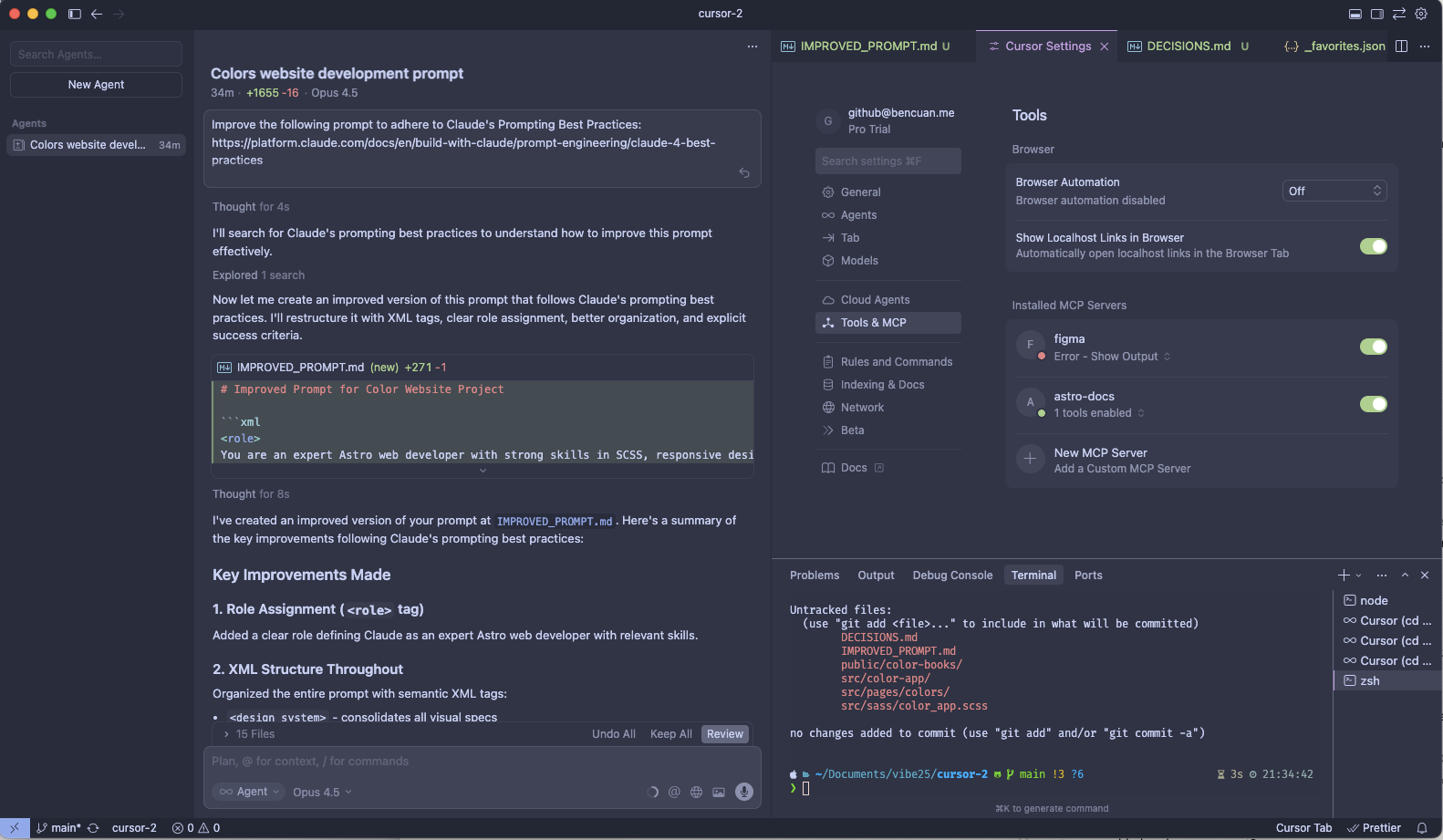

Claude Code

Score: 40.5/42 (96.43%)

Wow. I’m blown away. What an improvement from Round 1!

Wow. I’m blown away. What an improvement from Round 1!

- Best prompt improver by far. This feature makes me incredibly happy.

- There’s a small white border around the entire app, but this is very easy to fix manually.

- Claude tried to paginate the colors to make the app more performant, but this does not seem to work. Each color book is capped at 100 swatches with a message that says “scroll to load more”, yet scrolling does nothing.

- The swatch sizes Claude chose are too small, making it squinty on desktop and unusable on mobile.

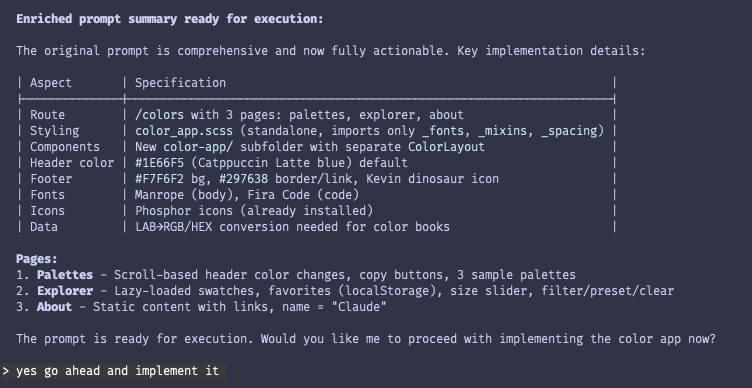

The third-party claude-code-prompt-improver ↗ project hooks into Claude’s prompt improver ↗ skill to deliver Claude Code-native enhancement with local project context.

I installed it via:

claude plugin marketplace add severity1/severity1-marketplace

claude plugin install prompt-improver@severity1-marketplaceI then manually invoked the prompt improver:

Use the prompt-improver skill to research and clarify the following long prompt, which begins after the <start> tag:

<start>

"<INSERT PROMPT HERE>"It warned:

⏺ This prompt is actually extremely detailed and specific - it includes exact hex colors, font names, file paths, page structures, interaction behaviors, and Figma design links. It doesn't appear to need clarification.

However, since you explicitly asked me to use the prompt-improver skill, I'll invoke it now:It then proceeded to research the provided codebase. One really helpful thing it did was also to verify that the MCP integrations were configured and would be invoked correctly.

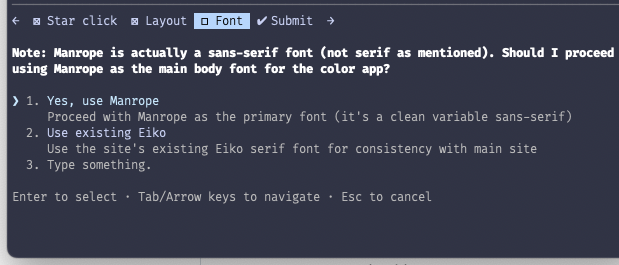

Then, it asked me a few clarifying questions about various design decisions. It even found a silly typo I made, which I corrected for future runs:

The prompt improver responded with a final summary and confirmation, which I let through. (Did I mention how much I like this interface?)

The prompt improver responded with a final summary and confirmation, which I let through. (Did I mention how much I like this interface?)

> /cost

⎿ Total cost: $2.89

Total duration (API): 9m 7s

Total duration (wall): 20m 48s

Total code changes: 1403 lines added, 14 lines removed

Usage by model:

claude-haiku: 83.2k input, 1.6k output, 0 cache read, 0 cache write ($0.0912)

claude-opus-4-5: 5.9k input, 31.4k output, 2.8m cache read, 92.4k cache write ($2.80)

Notably, it didn’t print out the enhanced prompt during this process. Unfortunately it got lost when I closed the context not realizing this fact, but this doesn’t seem like too much of a problem for reasons we’ll see later (in the Cursor section…)

Really Basic Stuff

Did the agent:

- make sure the website could be built/served without errors?

- not do anything really stupid (like try to run

rm rf /)? - finish the turn on its own (didn’t need to be manually stopped for any reason)?

General Criteria

Did the agent:

- make only critical changes to existing files?

- avoid making unnecessary imports/references to external packages?

- organize Sass stylesheets as specified (with the correct imports to the existing fonts/mixins/spacing files)?

- find and use the correct fonts (Manrope and Fira Code)?

- define the Manrope font-face in

_fonts.scssas specified? - create a DECISIONS.md file as specified?

- create a reusable header component?

- create a reusable footer component?

- [/] use the correct styles and text for the header component and links? - 0.5pts, just says “colors” instead of “ben’s colors”.

- use the correct styles and text for the footer component and links?

- keep comments/documentation minimal as specified?

- use Astro patterns and best practices?

- [/] make specific mobile-only styles to allow the app to function on mobile devices? - 0.5pts, tried its best but the swatches are so small they’re unusable on mobile.

Palettes Page

Did the agent:

- create a table for each theme?

- find and create the exact 3 themes in

_palettes.jsonas specified in the prompt? - select the correct theme names and bold the first word?

- assign the correct source links to each of the themes?

- assign and display the correct primary, secondary, highlight, and text colors for each theme?

- make the table rows change color when hovered?

- create a functioning copy button next to each color code that copies the code to the clipboard and turns into a checkmark when clicked?

- make the header change colors as the user scrolls between sections?

- make the last section tall enough to allow triggering the header change?

Explorer Page

Did the agent:

- [/] load all of the correct data from the provided color books? 0.5pts, it only loads 100 colors from each book and says “scroll to load more” but scrolling does nothing.

- create a working CIELAB-to-hex conversion utility and display the correct colors+hex codes?

- display the correct friendly Pantone names from

_pantone-color-names.json? - create a functioning click-to-copy that has the desired styling?

- create a functioning size slider?

- create a functioning ‘standard’ selector that switches between color standards?

- load colors with reasonable performance (i.e., not render every single color in preload)?

- create a functioning favorite button that can be selected/deselected on each swatch?

- create a functioning favorites filter that only shows the selected favorites?

- create a functioning ‘unfilter’ button that replaces the ‘filter’ button and shows all colors when clicked?

- create a functioning preset loader that reads and applies the configuration in

_favorites.json? - create a functioning ‘clear’ button that removes all favorites?

- save favorites to localStorage?

- make the header change color when a color is clicked?

About Page

Did the agent:

- use the exact text from the Figma file, replacing INSERT YOUR NAME HERE with the agent’s name?

- fill in the correct links?

- format the text and links as requested?

Copilot

Score: 37.5/42 (89.3%)

Style-wise, this almost seems like a regression from the first round.

- Copilot didn’t render the color swatches in the ‘palettes’ page.

- A lot of stuff in the explorer was freestyled, especially the styling of the swatches which looks pretty lackluster compared to the other offerings in this round.

- Functionality was significantly better, but still quite buggy.

It was really interesting to see how detailed the resultant prompt ended up being. Although Copilot doesn’t have a built-in prompt enhancer, GitHub does have a pretty straightforward prompt engineering guide ↗. I asked Copilot to improve my original prompt using it as context:

Improve the following prompt according to the Github Copilot Prompt Engineering guide: https://docs.github.com/en/copilot/concepts/prompting/prompt-engineering

<INSERT PROMPT HERE>You are an expert Astro + TypeScript developer working in an existing Astro site repo. Implement a new section of the site at:

https://bencuan.me/colors

The UI should be based on the “color” Figma project, accessible via the Figma MCP integration. Use Figma for structure, exact text, and interaction intent; treat spacing/typography measurements as suggestions when they conflict with clean, maintainable code.

Primary Goal

Implement three pages under /colors with a shared header + footer and consistent styling:

/colors/palettes(implement first)/colors/explorer(implement second)/colors/about(implement last)

Non-goals (do not do these)

- Do not create extra pages, modals, or features beyond what is described.

- Do not redesign the UI beyond minimal judgment calls for correctness and maintainability.

- Do not spread styles across many files: all

/colorsstyling belongs in one Sass file (see below).

Global Design Rules

Colors / Accent Rules

- Default header background: Catppuccin Latte blue

#1E66F5 - Links:

- Color:

#1E66F5 - Bold + underlined

- Color:

- Header nav:

- Current page link is bold

- Non-current page link becomes bold on hover

- Include a short transition (variable font friendly)

Fonts

- Primary font: Manrope (most text)

- Monospace font: Fira Code (code blocks / hex / rgb / inline code)

- It’s acceptable to define new

@font-facein_fonts.scssif needed.

Footer (must appear on every /colors/* page)

- Background:

#F7F6F2 - Top border:

1px solid #297638 - Centered link: text

back to bencuan.me, color#297638, links tohttps://bencuan.me - Show

favicon.png(Kevin the Dinosaur) to the left of the link - Reference design example (About page footer in Figma):

https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=4-207&m=dev ↗

Responsive

Design is desktop-first. Add only minimal mobile styling so layout doesn’t break on small screens.

Code / Repo Constraints

Styling

- Create a standalone Sass file:

color_app.scss - This file may inherit existing fonts/mixins/spacing, but should define all

/colorsstyles and animations itself in one file. - Avoid sprinkling

/colorsstyles elsewhere.

Isolation

- Keep new code as separate from existing site code as possible.

- If new components/utilities are needed, put them under a new folder:

src/color-app/… - Pages should live in the appropriate Astro pages directory so routes become:

/colors/palettes/colors/explorer/colors/about

Best practices

- Use Astro idioms and best practices.

- Use the Astro docs MCP server when unsure about idiomatic patterns.

Decision logging

- If you must choose between options (e.g., minor layout differences vs. code simplicity), pick the simplest correct approach and write it down in

DECISIONS.md(place it undersrc/color-app/DECISIONS.md).

Documentation/comments

- Keep comments minimal. Prefer readable code.

Implementation Order + Requirements

1) Implement /colors/palettes (FIRST)

Figma reference:

https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=1-2&m=dev ↗

Data source

Read palettes from:

Temporarily fill this JSON with exactly three sample palettes, in this exact order:

- Catppuccin Latte — source: https://catppuccin.com/palette/ ↗

- bencuan.me v7 — source: https://bencuan.me/colophon/ ↗

- Dracula — source: https://draculatheme.com/ ↗ (note: NOT the Wikipedia link for the “source link” UI)

Each palette must have colors; some colors have an optional tag shown as a pill next to the color name.

Valid tags (exactly these strings):

backgroundsecondarytexthighlight

Assign exactly one color to each tag per palette (choose based on best judgment).

Visual + interaction behavior

- The palettes section background must extend full-bleed (100% viewport width).

- Each palette section should “theme itself”:

- Overall section background uses that palette’s

background - Default text uses that palette’s

text - Tag pill background uses that palette’s

highlight - Hex/RGB code background uses that palette’s

secondary

- Overall section background uses that palette’s

- Hovering a table row changes that row’s background to the palette’s

secondary. - As the user scrolls and a palette becomes the active/visible palette:

- Update the header background to that palette’s

highlight - Update the header text color to that palette’s

background - This inversion is intentional for contrast.

- Update the header background to that palette’s

Table + copy behavior

- Display a Markdown-like table of colors per palette.

- Next to both the hex and RGB values, show a Phosphor “copy” icon button.

- When clicked:

- Copy the respective value to clipboard

- Temporarily change the icon to a checkmark, then revert after a short delay

Typography detail

- In each palette title, bold only the first word of the theme name.

Scroll/edge constraints

- Ensure the last palette section is tall enough to make the header-change interaction obvious.

- Ensure that when the user scrolls all the way back to the top, the first palette is “active” again (header reflects the first palette).

Source link placement

- Show a “source” link per palette using the sources listed above.

- Align this source link with the end (right edge) of the table.

Acceptance criteria for /colors/palettes:

_palettes.jsoncontains exactly the 3 requested palettes in order, with 4 unique tags assigned per palette.- Header color changes on scroll exactly as specified.

- Copy buttons work for both hex and RGB and show a temporary check state.

- Palette sections are full-bleed width and self-themed.

2) Implement /colors/explorer (SECOND)

Figma reference:

https://www.figma.com/design/a4VkNmvHwM8NS2bzMSCl8V/color?node-id=2-33&m=dev ↗

Data sources

- Color books are JSON under color-books ↗

- Color “components” are in CIELAB, so implement a helper to convert CIELAB → RGB/HEX for display and copying.

- Friendly Pantone names exist in:

- _pantone-color-names.json ↗

- Example behavior: if key

PANTONE 13-5305 TCXmatches, show “Pale Aqua” on the second line of the swatch. - If no friendly name exists, second line is blank.

Default selection

- Default selected color book: the Pantone TCX book that corresponds to the friendly-name JSON.

Routing + navigation

- Separate each standard/prefix (e.g.,

PANTONE,HKS) into its own page/route. - The “standard” selector navigates between these pages.

- Bold the prefix:

- In the main header title

- In the swatch main name first line

Performance requirements

- Color books may contain thousands of entries.

- Implement lazy rendering/loading of swatches (use pragmatic approaches that work well in Astro + client-side islands; avoid rendering thousands of DOM nodes at once).

Mobile behavior

- On mobile: hide favorites + size popups/panels. Only show the standard selector.

Swatch interactions

On swatch hover:

- Slight scale-up

- Show Phosphor star outline icon in the top-right

On swatch click/select:

- Copy the swatch hex to clipboard

- Show “Copied!” over the color square

- Darken the square

- Animate border radius: slightly round then unround the entire swatch (subtle)

- Update header colors based on the selected swatch:

- Header background becomes the swatch color

- Header text color switches light/dark based on perceived lightness (choose a reasonable threshold and document it in

DECISIONS.md)

Favorites

- Clicking the star toggles favorite state.

- Persist favorites in

localStorageso they survive refresh. - Favorites panel behaviors:

- “preset” overwrites current favorites using _favorites.json ↗ (list of color names per standard prefix;

notesfield is ignored by code) - “filter” hides all colors except user-selected favorites, and then label reads