you know it; I know it. From the Transit app’s NYC rat detector ↗ to a guest appearance ↗ of BART’s screech in the horror game Dead Space, American mass transit sits squarely in the “needs improvement” category.

In the face of all the doom and gloom, I’m actually here to spread some unreserved optimism: I believe the improvement we so desperately need is real, it’s coming, and much faster than you might think.

To celebrate one of the most exciting years in recent Bay Area transit history, I’d like to highlight some recent developments, and things to look out for in the near future!

table of contents

- why should you (and i) care so much about this?

- the story so far: an indirect, abbreviated attempt at history from a non-historian

- what’s new?

- BART’s fleet of the future

- Caltrain electrification

- L Taraval reconstruction

- what’s next?

- BART’s new fare gates

- Self-driving cars

- Muni signaling upgrades (i.e. no more floppy disks)

- Geary Subway

- SMART expansions

- Second transbay tube

- Caltrain’s Downtown Extension

- Silicon Valley BART extension

- Caltrain grade separations

- Central Subway Extension

- CA High Speed Rail

- Bay Area 2050

- footnote: how we can help

I. why should you (and i) care so much about this?

Growing up, my grandparents would take me and my brother all around the bay on what felt like grand adventures at the time. We’d hop on the Muni, Caltrain, and even (gasp) VTA in rather rowdy accompaniment of their shopping excursions to the various booming shopping malls of the early 2000’s. My memories of being on trains are much more vivid than they have any right to be; since we lived in the suburbs miles from the closest train stop, I’m sure we spent several orders of magnitude more time driving around than commuting by rail.

I’m sure much of my love for the Bay Area’s struggling transit systems is rose-tinted by nostalgia. But even so, and even after visiting a bunch of places with truly world-class transit (Tokyo, Seoul, Hong Kong, Amsterdam, Barcelona, etc etc)

a. the urbanist’s argument

Recently, the concept of urbanism ↗ seems to be in the beginning stages of taking off- especially as internet personalities like Not Just Bikes ↗ grow their following and the YIMBY coalition ↗ continues to gain traction alongside skyrocketing rent prices.

I wouldn’t consider the urbanist movement mainstream; the average American shan’t be bothered by the atrocities of municipal zoning laws. Anecdotally, though, the number of people I meet who casually use urbanist lingo like “stroad” and “mixed use development” when talking about their neighborhoods continues to grow by the day.

While popular urbanism is far from infallible (I fault it for being obscenely idealistic at times), I think the movement is a big positive step towards promoting healthy discourse around our built environment and how we can start making things better.

They also bring a lot of recyclable talking points for those of you who like to sift through facts and/or data:

-

Cars, roads, and parking lots take up a lot of space that could be better utilized by shops, restaurants, and homes. It is very hard to contest the fact that a canal is way nicer than a four-lane highway. ↗

-

Riding transit is significantly safer than driving. For example, BART measured 18 times fewer fatalities ↗ per passenger mile compared to personal vehicles in 2022 (0.03 vs. 0.54).

-

Riding transit is significantly cheaper than driving. Factoring in gas, maintenance, insurance, parking, tolls, and depreciation, I end up paying around $1000/month to own a car. That’s only slightly less than the amount I pay for an entire year of riding transit 3-5 days a week! (I could even throw in an extremely nice e-bike purchase once a year and still be way under.)

-

Every full bus takes up to 30 cars off the road; every full BART or Caltrain dispatch takes off somewhere between 500 and 1,000. If transit gets better, more people will take it instead of driving, and the notorious north-south Bay Area traffic might finally be tamed.

My biggest takeaway from all of this is that transit and driving are not a zero-sum game. If we improve our transit systems, the world becomes better for drivers and pedestrians, too!

b. a tangent on freedom

While all of those things are great, the main reason I care so much is slightly more intangible: I find that I enjoy the kind of freedom offered by mass transit much more than I do the kind of freedom offered by driving a car.

The difference between these kinds of freedom mostly revolves around responsibility, or a lack thereof. On a train, I can zone out, sleep, read a book, stare out the window at the passing scenery; while driving, paying attention to the oncoming road is literally a matter of life or death. An hour in a car very much feels like an hour; an hour on a train produced a few hundred words of the post you’re reading right now.

Relatedly, there’s the concept of the freedom to not drive ↗. Driving is enjoyable in many circumstances- but for every person who wants to be driving, there’s someone who has no choice but to drive, tailgating and dangerously weaving in a frustrated bid to escape their personal hell a few minutes faster.

c. an even bigger tangent on induced demand

In the everlasting battle against soul-crushing traffic, numerous studies support one surprising outcome: adding more lanes to freeways makes traffic move _ slower_ , not faster.

This is the phenomenon of induced demand in action— simply put, if you build it, they will come. (Here’s a nice intro video ↗ if you’re confused, which I was too!)

At a macro scale, induced demand implies a few notable consequences:

-

Traffic cannot be solved with road infrastructure alone.

-

Building more lanes displaces local residents and encourages commuters to live further away from city centers. This further increases sprawl, commute times, and of course traffic.

A reasonable conclusion to make here: if we want to solve traffic, the only sustainable solution is to take cars off the road.

I feel like this is something Hong Kong does particularly well. Despite having a population of 7 million and an expansive network of six-lane highways that would make us Americans proud, there’s hardly any traffic. Over 90% of commutes are done via transit, which makes it easy for the rare driver (and, more importantly, the buses/trams) to zoom along the busiest roads in the city during rush hour. It’s a win-win for everyone, whether for the subway passenger enjoying 3-minute headways or the taxi drivers easily navigating the empty streets.

another tangent on the even bigger tangent on induced demand

“So”, somebody must have said, “if adding lanes is so bad, what if we tried deleting lanes instead?”

In 2018, BART’s Regional Measure 3 passed with 55% of the vote. This allocated $4.5 billion to transit initiatives, part of which was funded by the headlining $1 bridge toll increase.

The fine print included lots of nice goodies like ferry upgrades, new BART cars, and improvements to the Salesforce Transit Center. And, tacked onto that list was an overhaul of the Bay Area’s most crowded HOV lanes into toll lanes.

This was, and still is, highly controversial: at peak hours, the express lane pricing shoots through the roof. I’ve seen 2-mile stretches cost $12.50 to enter, as drivers in the slow lanes enviously eye the cars zooming by.

But the fact is, the toll lanes are working — in 2023, they generated $123 million in revenue ↗ and increased the average speed in the lane by 15-20 miles per hour. Once the construction costs are paid off, this revenue can be put back into transit and road improvements.

d. on community, and prioritization

Here is the closing argument I’ll make in the case for better transit: cities are much nicer when they’re built for people, and not cars.

We’ve seen the firsthand effects of this mindset shift over the past few decades. For example, Hayes Valley used to look like this!

And here’s a before-and-after of the Embarcadero:

What used to be two of the grimiest neighborhoods in the city are now among the nicest, most popular places to be. Walking through the picturesque waterfront alongside the Ferry Building, or browsing the shops near Patricia’s Green makes me (and its residents) happy in a way that a loud, looming concrete tube could never.

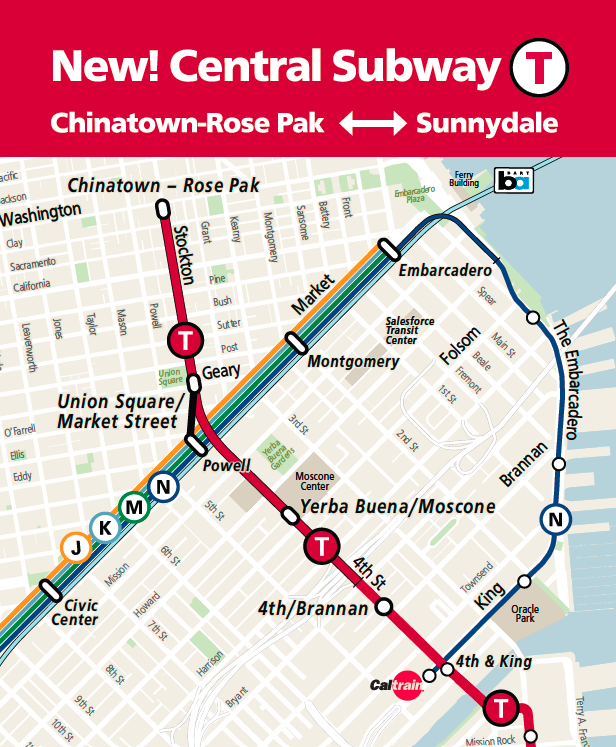

This, however, comes at the cost of the people whose commutes are now longer, and the businesses on the other side who get fewer visitors. One of the neighborhoods hit the hardest by these freeway removals was Chinatown, whose shops struggled to stay open. Today, thanks to years of advocacy by Rose Pak ↗ and other activists, we now have the Central Subway as direct replacement to the freeways.

While it’s still not perfect, it’s inspiring to see an example of how we can, and should, reclaim our city centers for living and thriving.

II. the story so far

I’m not a historian, and attempting to cover the vast history of transportation in the Bay Area would take me far out of my depth.

So here’s a cliffnotes-FAQ-summary-timeline-thing, brought to you by Wikipedia and this video ↗:

-

Throughout the mid-to-late 1800s, transit in San Francisco was privately owned, with a dozen companies running their own routes while jockeying for rider share.

-

In 1863, the Peninsula Commute line began serving riders from San Francisco to San Jose. (This line would become Caltrain nearly a hundred years later.)

-

In 1873, the first cable car line in North America ↗ opened in San Francisco. Cable cars would continue to grow in popularity, replacing traditional streetcars.

-

The first transbay direct rail-to-ferry line, operated by the San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose Railway Company, opens in 1903.

-

Most transit lines were damaged beyond repair in the 1906 earthquake and subsequent fire, but lines quickly bounced back as the city rebuilt.

-

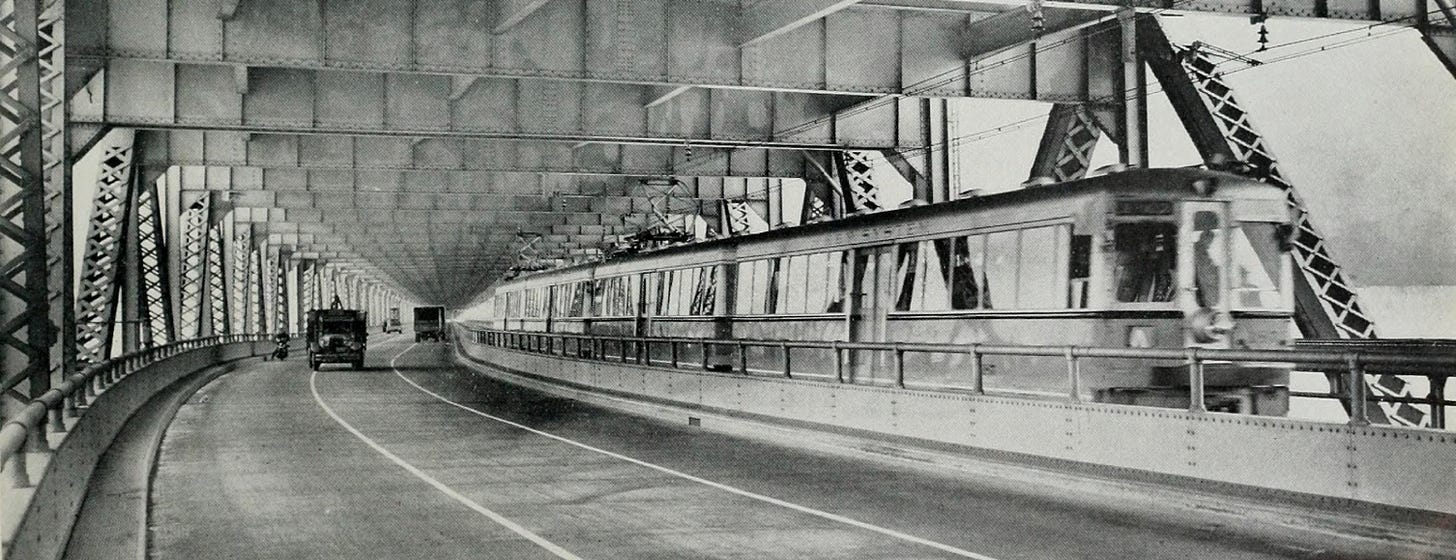

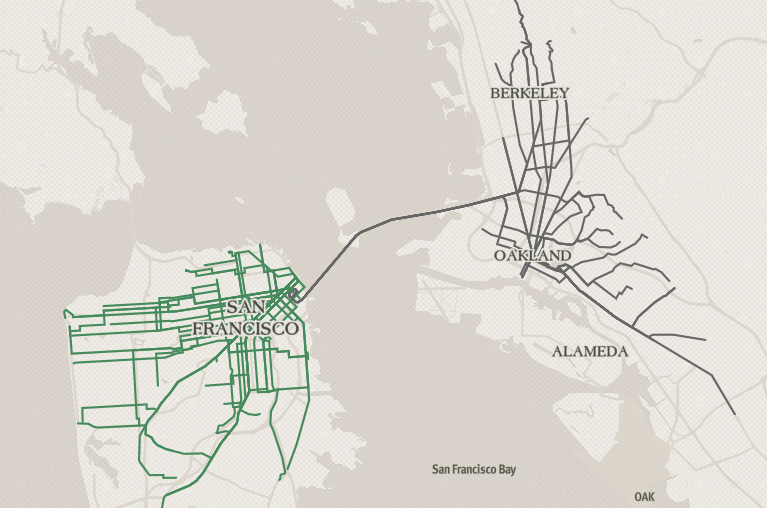

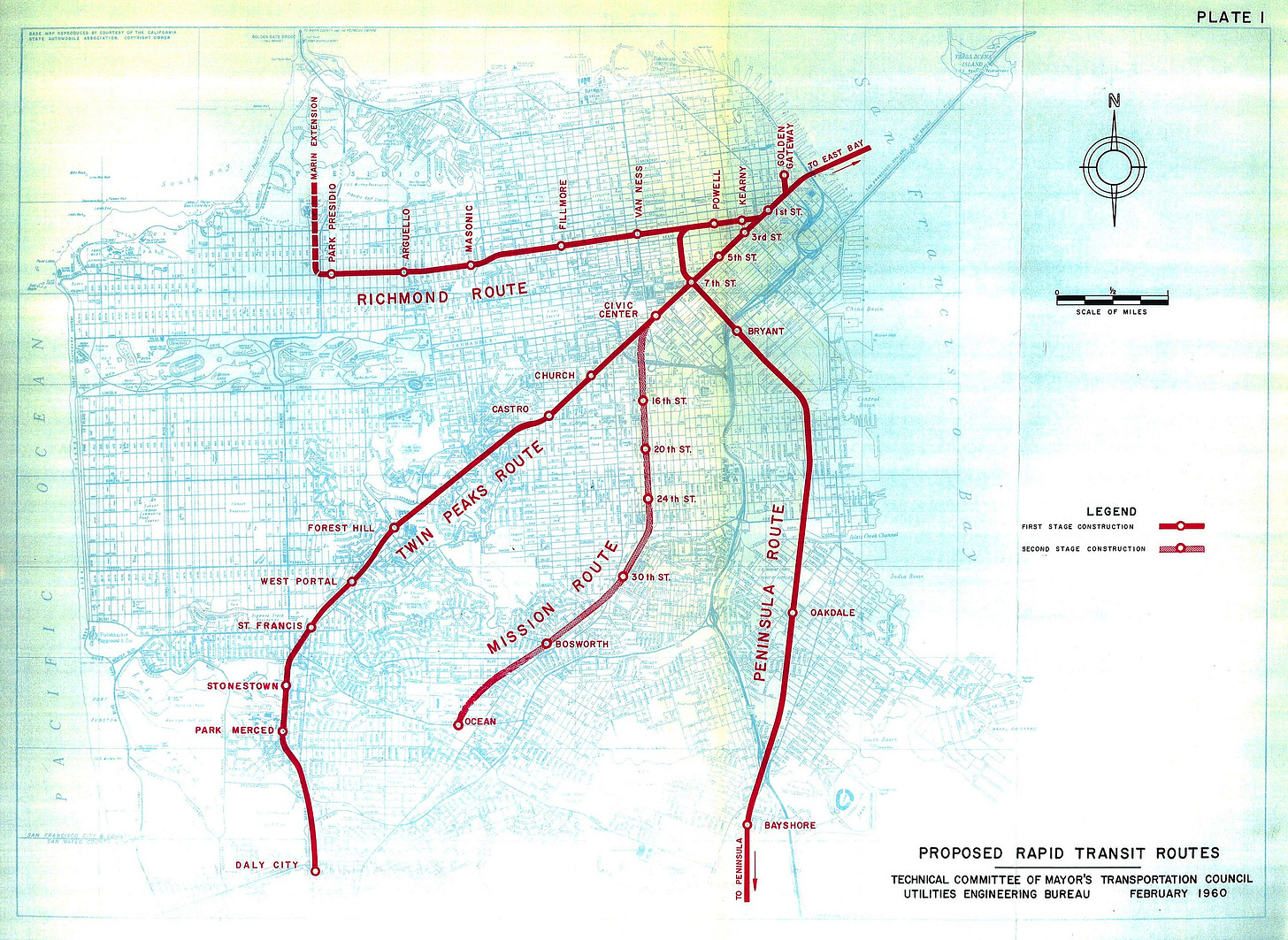

After more consolidation, the SF railways were largely controlled by the Union Railroads Company, and the East Bay railways were controlled by the Key System. This period of time, from the 1920s to 1950s, would mark the peak of transit in SF, as illustrated by this map:

-

The Bay Bridge opened in 1936, with the Golden Gate Bridge following shortly in 1937. The Key System ran a rail line across the Bay Bridge for a time, but the bridges marked the beginning of the shift towards cars and buses, away from rail-based transit.

-

Today’s Muni system, which is publicly owned and operated by the city of San Francisco, took control of nearly all of the city’s rail lines by 1952. Due to lobbying from car/oil companies and pressure from increased demands from car owners, Muni would dismantle all of its rail lines by 1956 except for the ones which survive today (J, K, L, M, and N lines).

-

BART opened its first line on September 11, 1972 between Fremont and MacArthur stations. The Transbay Tube opened in 1974, finally restoring rail service between SF and the East Bay.

-

Caltrain begins operations in 1985, as Caltrans assumes control after Southern Pacific threatens to discontinue the Peninsula Commute amid declining ridership.

-

BART opens its long-awaited connection to the San Francisco International Airport in 2003. The Oakland Airport connector would follow ten years later, in 2014.

-

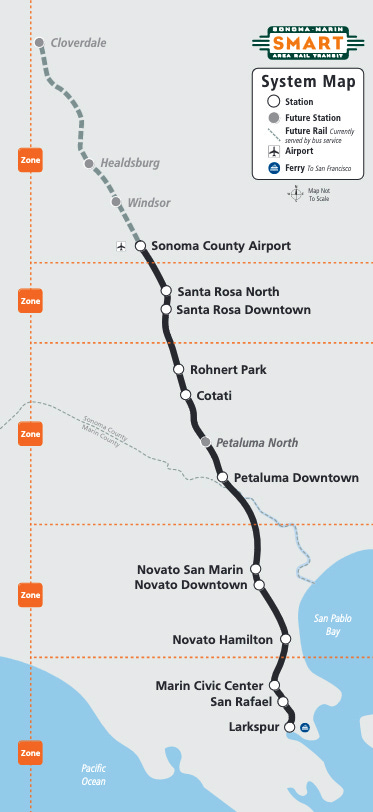

The Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit line (SMART) opens on August 25, 2017, marking the beginning of modern passenger rail service in the North Bay.

-

In 2023, the Central Subway opens as Muni’s first new underground metro line in nearly a hundred years. This reroutes the T line to follow 4th Street through downtown, terminating in Chinatown.

And, here’s a big list of resources vaguely ordered by level of enjoyment, that I would recommend if you’re a transit nerd and/or just want to learn more :)

-

The Bay Area’s Lost Streetcars ↗ : interactive maps and photo archives documenting the devolution of the streetcar networks of SF and the East Bay.

-

Tunnel Vision: An Unauthorized BART Ride ↗ : it’s hard to describe this film in a way that can truly express my appreciation for it. Go watch it! “*BART isn’t perfect, but in a way it’s better than perfect: it’s the only thing that could have worked, executed with the slimmest of margins in the narrowest window of history… we did not have the technology to build BART any sooner, nor did we have the money to afford BART any later. The trains were exactly on time.”

-

Portal ↗ : a pretty well-written, engaging history about the history of San Francisco’s urban fabric, centered around the story behind the Ferry Building. One-star-worthy on my bookshelf!

-

Fog City History ↗ : A small YouTube channel that only has two videos as of writing, but they’re both incredible.

-

The evolution of San Francisco public transit ↗ : A chronological video walkthrough from 1847 to 2020.

-

A History of BART ↗ : a succinct summary, with lots of fun archival photos/videos, from the official BART website.

-

BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System ↗ : if the BART website was too short and you want the full book version of it.

III. what’s new?

The past year has been super exciting! Lots of long-anticipated, major changes. Here are three of the big ones:

September 11, 2023: BART replaces the entire legacy fleet

Only OGs remember: the old screech; the faux-vinyl seats; the robotic sound of “8 car 2 door Richmond train now approaching platform 1” echoing throughout the station.

For fifty years, the legacy fleet dutifully served the Bay Area— but now, covered in decades of grime and far older than their expected lifespan, it was time for them to retire.

Although the first of the new cars (also known as the Fleet of the Future) started carrying passengers in 2018, technical difficulties and production delays meant it would be years before the entire fleet could be replaced. And finally, just last year, they did it— $394 million below budget ↗, too!

The new cars are brighter, roomier, cleaner, and quieter. As of today, all 775 ordered by the project are fully in service, with a few hundred more on the way to get trains back up to their full 10-car length (these days, they’re usually 6 or 8 cars long, and can get super crowded during rush hour).

September 21, 2024: Caltrain goes electric

If the new BART cars were a night-and-day difference, the arrival of Caltrain’s new electric fleet was like a resident of Longyearbyen seeing a sunrise for the first time in six months.

Here’s a fun comparison video ↗. The new trains smoke the old ones!

The new trains are incredible - if stacked against European networks in terms of frequency, speed, and quality, I have no doubt they’d hold their own. What was once a 35-minute commute for me got cut to a 25-minute one overnight, with headways going from 30 minutes to 15. We are finally in the 21st century :)

Getting this up was no easy task: unlike BART, which already had nearly all the power delivery facilities needed for the new trains, Caltrain was going from 0 to 1 with their electrification. Retrofitting overhead lines and power stations onto an extremely busy active corridor is a monumental feat!

September 28, 2024: L Taraval reopens

As one of the original streetcar lines in San Francisco, the L line is one of the most important corridors for residents of the Sunset District. For five years, Taraval Street has been a tangled mess of construction, and woefully inadequate buses subbed in for the trams as Muni completely redid the entire street from the beach to West Portal.

Since the trams run in the center of the road, passengers had to cross two lanes of busy car traffic to board at stops, some of which didn’t even have platforms! Given these safety concerns, the new Taraval Street is a huge step up for pedestrians and transit riders. The street is now two lanes instead of four in most places, with proper waiting platforms, signaling, and crosswalks.

IV. what’s next?

BART’s new fare gates

Optimism level: super high!

It’s no secret: BART has a safety problem. Or rather, it’s actually super safe- many multiples safer than driving- but the general perception of BART trains used to fall somewhere in between public toilet and drug den. NBC Bay Area did a fantastic investigation called Derailed ↗ a few years back and found some pretty horrifying shenanigans going on both en-route and behind the scenes of BART’s police force.

One of the many causes of this symptom is fare evasion: the old fare gates were notoriously easy to jump, and BART seemed to have some unspoken policy of ignoring the jumpers in fear of retaliation. It’s fair to assume most of the drug addicts and unhinged knife-brandishers didn’t tap their Clipper cards to get on the train.

The new gates aren’t perfect ↗, and it’s still possible to force your way through them without paying— but it’s significantly harder than before. We shall have to wait for the initial reports to see how much they’re improving safety (and whether or not the increased fares will make up for their installation cost)- but I’m extremely optimistic about considering this a huge improvement for BART.

Self-driving cars?!

Optimism level: ???

Self-driving cars have been a staple of sci-fi/futurist literature for almost as long as cars themselves existed in the public mind. They really started taking off as a “wow, this might actually happen” reality in the 2010’s as Waymo, Tesla, BMW, and lot of other car manufacturers hopped on the R&D hype train.

And since 2022, you and I can hop in one for approximately the same price as a regular rideshare (assuming you’re in SF, Phoenix, or LA at time of writing)!

Generally, I’ve found the them to make people go ‘whoa’ the first time they ride one- but it’s surprising how quickly it wears off. I recall it taking 10 or so minutes my first ride before it felt just like any other taxi service and I started checking the map to see how much longer it was before we arrived.

As of writing, Waymo’s San Francisco fleet contains 300 cars. This isn’t quite enough to satisfy the demand; wait times tend to be consistently longer than those of a comparable Uber or Lyft ride (typically 10-15 minutes). Once they figure out their distribution problem, Waymo hopes to expand their service area to most of the Peninsula— with the notable exception of SFO ↗, whose spokespeople are communicating a cautious “let’s wait and see” message with no clear plan ahead.

Cool factor aside, self-driving car services bring a lot to the table.

-

Autonomous vehicles are already safer than human drivers ↗ in most circumstances, and will continue to improve rapidly.

-

Some optimists (the most famous being Tesla ↗) imagine a future where robotaxis supersede the need for private vehicle ownership. While this is certainly in moonshot territory, the possibility of an extreme reduction in the number of cars and parking spaces shouldn’t be discounted.

-

Sitting in the passenger seat is usually way less stressful than driving— and will take a whole lot of reluctant drivers off the road. In other words, people who shouldn’t be driving (drunk drivers, road ragers) or shouldn’t need to drive (elders, people with disabilities) can now get around with the same convenience, but without all of their assumed risk, of driving.

On the other hand, self-driving cars have garnered a lot of deserved criticism; staunch opponents posit that they will actually make our transit problems worse. Transit consultant Jarrett Walker points out that transportation is primarily a geometry problem ↗, not an engineering problem: it’s physically impossible to replace trains and buses with private vehicles due to the amount of space they occupy on the streets.

So a bus with 40 people on it today is blown apart into, what, little driverless vans with an average of two each, a 20-fold increase in the number of vehicles? It doesn’t matter if they’re electric or driverless. Where will they all fit in the urban street? And when they take over, what room will be left for wider sidewalks, bike lanes, pocket parks, or indeed anything but a vast river of vehicles?

Not Just Bikes released a video ↗ a couple weeks ago about this topic, which falls squarely into the “staunch opposition” category. While he raises some very good points, this comment struck me in particular:

What was most surprising to me was that when I began researching this video (two years ago!) it was going to be about some of the technical challenges that would need to be overcome in order to make self-driving cars a reality, but the conclusion was going to be that ultimately, AVs would be a good thing. By the time I was done researching this topic I was absolutely horrified of our future self-driving dystopia. 😱

Personally, I’m garnering some reserved, and cautious, enthusiasm for the future of autonomous driving. I see it as a tool: neutral in itself, but could be either fantastic or disastrous depending on how we choose to harness the technology. It’s very possible that they create a second wave of car-dominated dystopia, but I think it’s just as possible that they’ll serve us well in a transitional period, making our roads safer and providing a new mobility option for non-drivers while the current shift towards transit-oriented urban thinking continues.

Muni gets better signalling

Optimism level: high

Muni gets memed on a lot for still relying on floppy disks for their central signaling control servers, which have been in service since the late 1990’s.

I’m happy to hear that this will soon no longer be the case ↗. For us riders, the benefits should be abundant— trains will be faster, more reliable, and come at a higher frequency once trains can be automatically controlled rather than manually driven. This will also (hopefully) mean that the Muni light rail cars will no longer get stuck in traffic, since their patterns can be automated to always sync up with traffic lights.

Muni currently predicts that the project will wrap up around 2034 ↗; given how unrealistic their past deadlines have been, I’d hope for them to come online sometime in the late 2030’s. But it’s happening, it’s fully funded, and it’s likely the highest-impact sections (like the street-level T and N sections near Oracle Park) will be completed first. For that, I’m highly optimistic about this project.

The Geary Subway

Optimism level: cautious

Since the 1930s, Geary Street has remained the most well-traveled, congested east-to-west corridor through San Francisco. Today, over 50,000 people ride one of the several bus lines spanning the street daily— which, by comparison, is a quarter of BART’s peak-weekday ridership!

Talks of a Geary Street subway date back as far as 1935 ↗, and have spilled over to its own Wikipedia page ↗. However, the closest we’ve ever gotten in recent times is the 2018 construction of a dedicated bus corridor ↗ through the busiest parts of the city, which while nice, is still woefully inadequate for the sheer volume of people moving back and forth.

As much as I would love to see it, a whole lot of friction remains between now and a better Geary Street. Connie Chan, the recently re-elected Richmond supervisor (and by extension, a majority of the Richmond District), is notoriously pro-car ↗and unlikely to advocate for new transit lines through the neighborhood that would disrupt the flow of traffic. At the same time, both BART and Muni will likely be preoccupied by their current enormous expansion projects for decades to come (the Silicon Valley Extension and the Central Subway— I’ll get to them soon!).

Will transit ever make it across the Golden Gate? It’s possible— though I’m skeptical it will happen within my lifetime. And while it’s much more likely for Muni to resurrect the old B line, it’s still not likely enough to consider myself anything more than cautiously optimistic that I’ll be able to see anything more than a bus route on Geary Street.

SMART to Healdsburg

Optimism level: high

As the Bay Area’s newest transit agency, SMART has everything to prove and nothing to lose. They’re doing pretty great, actually, closing in on a million yearly riders ↗ and improving regional mobility by building a 30-mile bike path ↗ along its corridor.

Their biggest win of the year, announced last month, was that they’d secured funding for an expansion to Healdsburg ↗. While still falling short of the original vision of a full 70-mile railway to Cloverdale, we’re getting really close!

SMART hasn’t come without criticism: train frequency is quite bad (30-minute peak headways!!!), and the brand new ferry connection at Larkspur requires a miserable 20-minute walk ↗ to catch. But given that the agency is still in its infancy, and that they’re enjoying rapid improvements while ironing out their current issues, I’m quite optimistic about SMART’s future.

A second transbay tube?

Optimism level: cautious

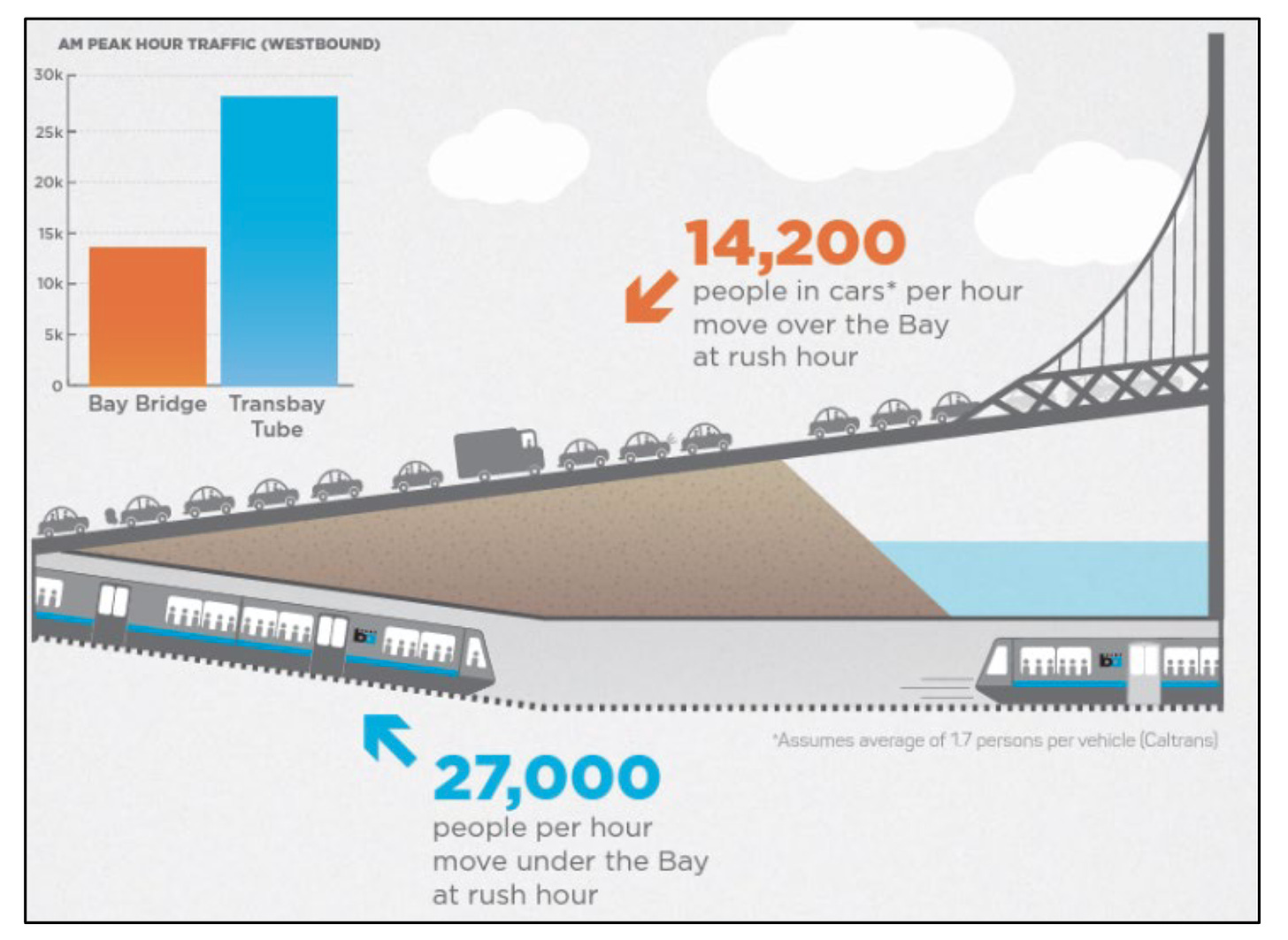

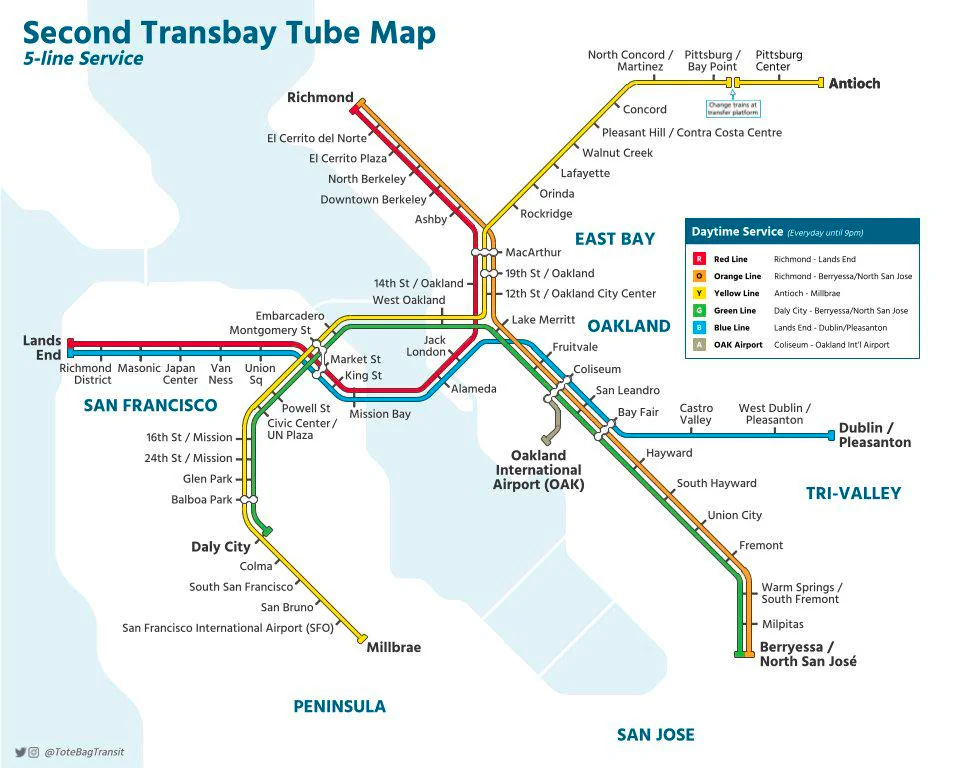

Right now, the biggest transit bottleneck in the Bay Area is the Transbay Tube. Spanning 3.6 miles, the submerged tunnel whisks over 25,000 people per hour between SF and Oakland at peak times.`

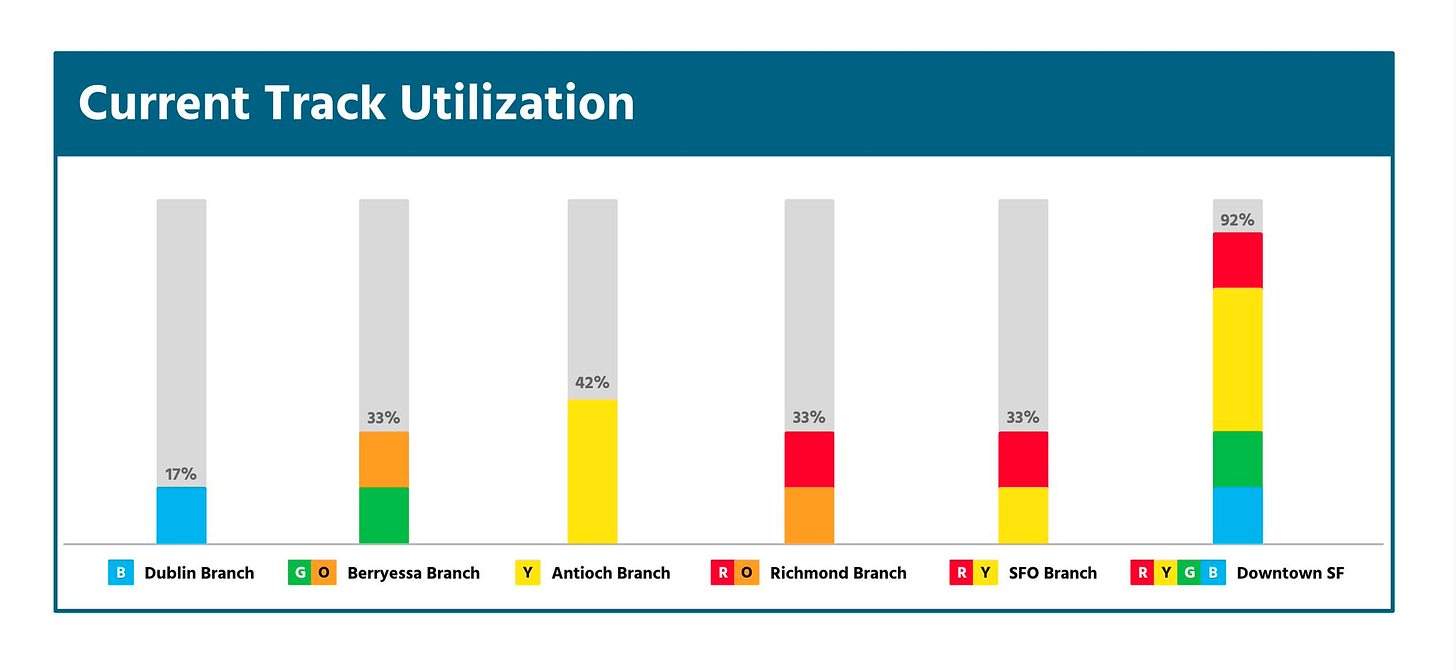

Since four of the five BART lines pass through the tube, it pretty much operates at 100% capacity, with trains coming once every few minutes per direction on average! This means the system as a whole is maxed out at 10- or 20-minute headways per line- and if we ever want to get more frequent trains, they’ll need to go somewhere.

The Bay Area’s various transit agencies seem determined to build a second underground connection between San Francisco and Oakland, but where it’ll go— and which agency it’ll belong to— are wildly open questions right now. I believe BART has the strongest bid at the moment, given they’ve already proven they can operate a transbay link productively and efficiently. Caltrain and Amtrak are also possible contenders for extending their existing commuter rail lines to the recently-constructed Salesforce Transit Center.

Given the lack of a plan, lack of funding, and lack of conviction at the present moment, I’m putting the Second Transbay Tube squarely in the ‘cautiously optimistic’ category. I personally think it’s slightly more likely to happen within my lifetime than a Geary Subway, but not by much.

Caltrain to Downtown SF

Optimism level: mid

Now that Caltrain is electrified (again, HUGE!!) its next biggest problem is that it dumps its SF-bound passengers in the middle of nowhere.

The current terminus at 4th and King is a good 25-minute bus/rail journey away from downtown (assuming you can catch a transfer!). Anecdotally, most people I know who commute up use a bike or scooter to get to their homes or offices in the city, which is suboptimal.

Today, the final Caltrain terminus lies partially constructed below the floors of the Salesforce Transit Center, patiently waiting for its fated connection to the rest of the system. Despite being less than 2 miles away from 4th and King, the stakes behind tunneling through SF’s busiest, densest business neighborhood are astronomical. The project’s current price tag, which includes a new underground station to replace the existing terminus, sits at around $5 billion ↗.

This is a project driven by sheer force of necessity, rather than practicality or economic viability. It’s going to be an uphill battle to build this thing, and as much as I’m all for it there’s a very real chance the end result isn’t going to be what we want or need. With that in mind, I’m moderately optimistic about the Caltrain Downtown Extension.

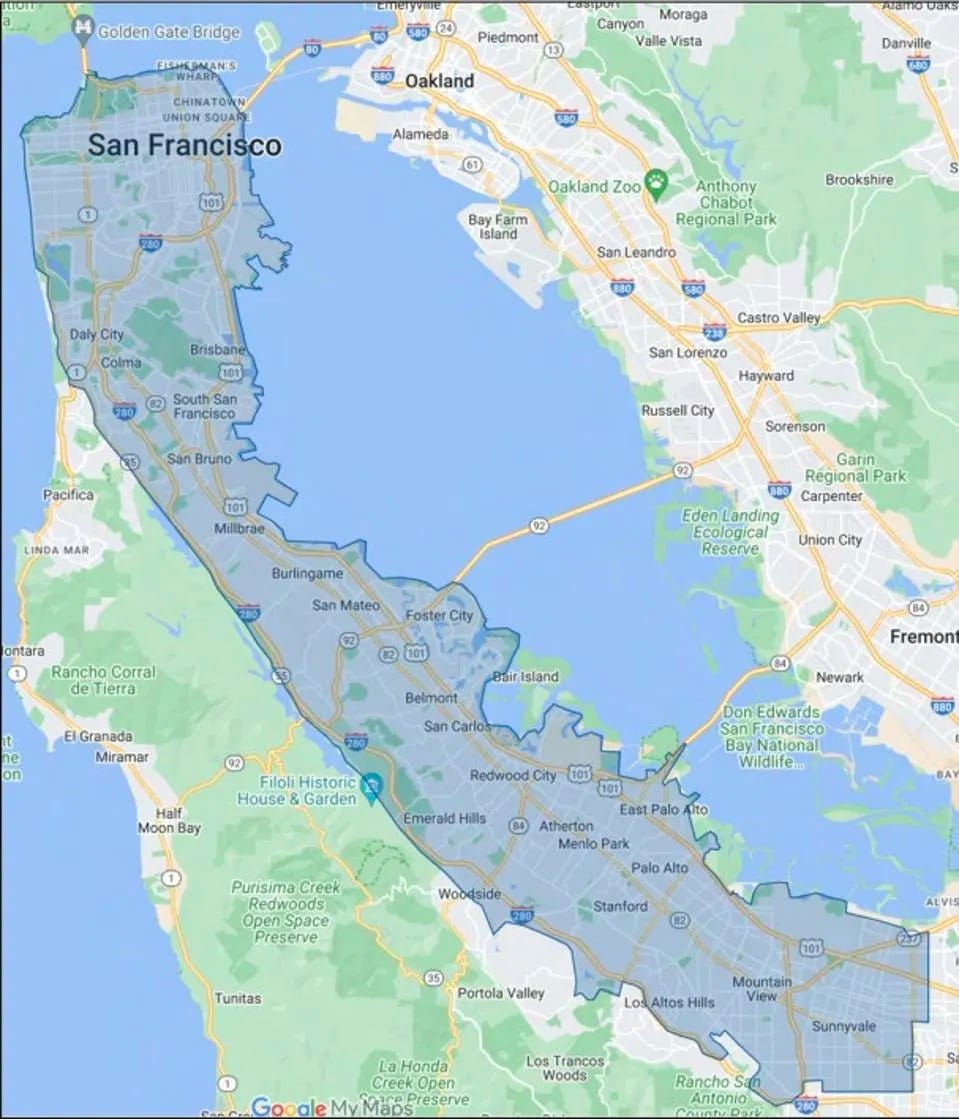

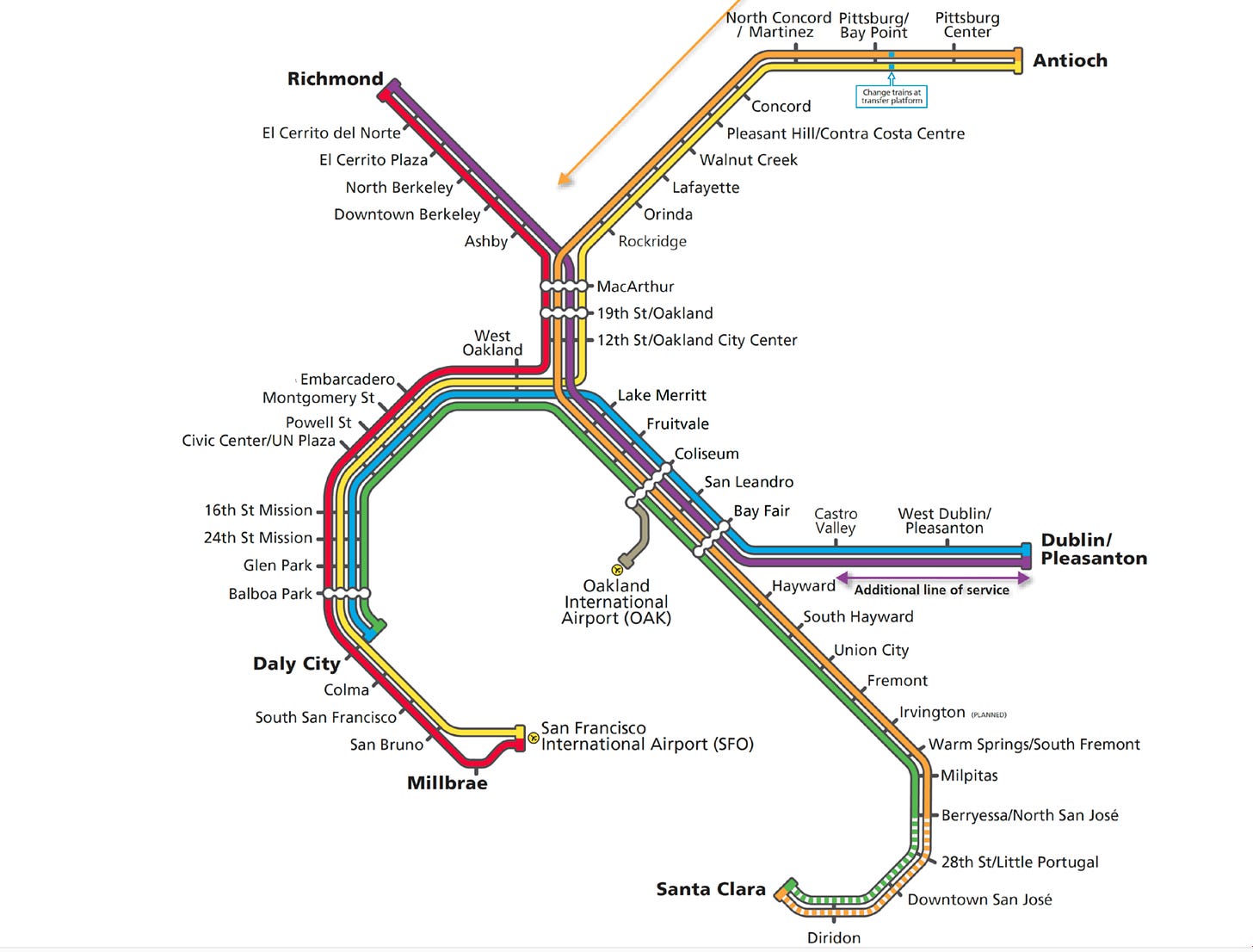

BART to Silicon Valley

Optimism level: mid

The second phase of BART’s Silicon Valley Extension was the most recent major project to break ground ↗ this June. When completed, BART will finally be able to take riders directly between the downtowns of the Bay Area’s three largest cities.

On paper, things are looking great: the federal government just committed $5 billion ↗ to the project (out of a $12.7 billion total budget), designs are finalized, and construction is under way!

I do, however, have a few reservations:

-

VTA is managing this section. VTA also manages one of the least effective light rail systems in the US as found by a civil grand jury ↗. As an example of a recent VTA initiative, a $453 million project to extend the Orange line was estimated to attract 611 new riders to the system. As a baseline I have absolutely no faith in the VTA to deliver, and am desperately hoping they’ll prove me wrong.

-

For some reason, the project design calls for a single-bore, horizontally-stacked tunnel section that looks like this:

There’s only one other single-bore subway system I can think of, which is Barcelona’s Line 9. Although it is a technological marvel and one of my favorite subway lines of all time, it is still not done, being nearly 20 years behind schedule and €5 billion behind budget. This does not bode well for BART, and I wonder what kind of analysis would have favored this unvalidated design over traditional twin-bore methods with well-established precedent.

So as much as I’d love to see BART reach downtown San Jose and think it’d be a massive bonus to the city, there’s so much room for this project to be better-managed. I hope other future projects- like Caltrain’s Downtown Extension- don’t get unduly punished by funding reallocations to the very-likely-to-go-over-budget Silicon Valley Extension.

Caltrain Grade Separations

Optimism level: high

Every year, collisions with Caltrain cause 10 or more fatalities ↗. A non-insignificant number of these occur at one of the corridor’s 71 at-grade crossings, where (often major) roads intersect with rail lines.

In addition to the human cost, these crossings are a major cause of delays both for the trains (whenever someone’s car gets stuck on the tracks) and the cars trying to cross (since they often need to wait several minutes for trains to pass). If Caltrain wants to maintain any guise of reliability, and eventually welcome high-speed trains, most of these crossings need to be grade-separated.

The most recent and notable grade-separation project was Hillsdale Station ↗, which eliminated three at-grade crossings in San Mateo and made one of the system’s busiest stations much safer for pedestrians.

At the time of writing, 30 at-grade crossings ↗ are under consideration for grade separation work. The most notable of the bunch, and the most likely to see construction the soonest, are:

-

The Broadway Grade Separation ↗ in Burlingame, which will re-introduce the currently-underserved Broadway Station, hopefully before the end of the decade;

-

The Rengstorff Grade Separation ↗ in Mountain View, which lies at one of the busiest cross-intersections in the city (Rengstorff Avenue x Central Expressway);

-

The Castro Street Grade Separation ↗ at the Mountain View station, which sees a huge amount of pedestrian and bicycle traffic of people trying to cross a currently dangerous intersection.

Given the very positive impacts from these relatively short, low-risk projects (especially compared to major rail line extensions), I’m super optimistic that we’ll see some shiny new grade separations pop up in the decade to come.

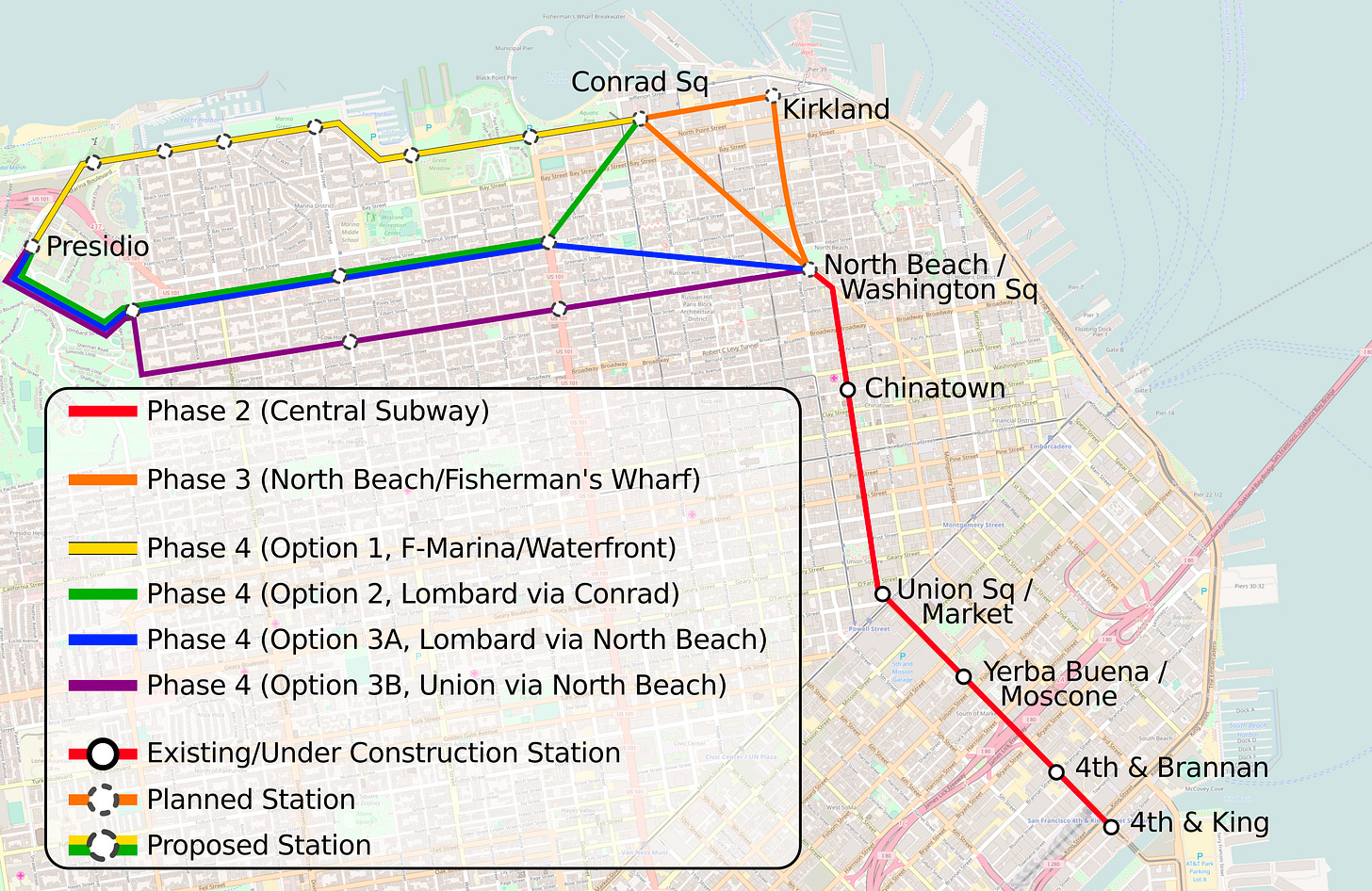

The Central Subway continues

Optimism level: mid

You may be aware that the T line currently looks like this:

But not-so-secretly, the tunnel actually extends half a mile further, since the closest place to dig the boring machines out was at Washington Square, at the intersection of Columbus Avenue and Union Street. This station, which would extend the T line to North Beach, unfortunately doesn’t look like it’ll be completed anytime soon given that it’s being lumped in with a much more ambitious extension project ↗.

Extending the Central Subway is much like Caltrain’s Downtown Extension in that it feels simultaneously inevitable and impossibly difficult. Easy, fast access between the main downtown corridors and the cultural hotspots in the Marina, North Beach, and Fisherman’s Wharf would completely transform San Francisco for the better.

Currently, the Central Subway Extension is still in its early planning phases, with several possible alignments under investigation:

I’m personally rooting for this project to roll forwards. There’s still a lot that needs to go right, but I’m hoping that the half-mile of already existing tunnel will give it the kickstart it so desperately needs.

California High Speed Rail

Optimism level: existential dread

sigh, I guess this post wouldn’t be complete without CAHSR…

This project is so controversial. Just go search for it anywhere on the internet— YouTube, Reddit, traditional news sites etc. etc. You’ll see thousands of people from across the political spectrum blasting California for setting $100 billion ablaze for a nowhere-to-nowhere railroad that could be most generously described as a “complete shitshow”; you’ll see just as many people arguing that this will singlehandedly save the Central Valley, and that the Shinkansen was 100% over budget but everyone adores it anyways and CAHSR will be exactly the same!

Out of all the squabbling going on out there, I think this Alan Fisher video ↗ is a must-watch if you want to figure out how you want to feel about this project. His main argument goes something like this:

-

CAHSR is doing alright, actually, and it’s getting way more negative press than it deserves.

-

The negative press mostly comes from two things: people and politicians not understanding trains (because they don’t really exist in the American zeitgeist), along with lobbying from car and plane companies.

-

Yes, a public works project as big as this is going to have lots of budget inefficiencies and probably some political corruption. But compared to the shenanigans in for-profit companies, our concern about this is blown wildly out of proportion.

-

Larger and more mismanaged infrastructure projects involving cars/freeways are currently ongoing and have no issue with bad press or funding shortfalls. We definitely have the ability to build this thing, yet we’re choosing not to believe in it.

I really, really, really want to see high-speed rail not only exist, but succeed and thrive, within my lifetime. But whether or not this dream is realistic is, unfortunately, still up for debate. Out of the 500 miles of a complete SF-to-LA route, the easiest, straightest, flattest 199 of them are currently under construction— and even that won’t be complete until the mid-2030s! The difficult parts of the route (namely, Pacheco Pass connecting Gilroy to the Central Valley and Tehachapi Pass connecting Bakersfield to LA) call for some insane tunneling and viaduct work and currently has zero funding. And given the recent political climate in the United States, it’s highly unlikely they’ll get anything for the next four years at the minimum.

I will continue to watch this project, hopefully with growing excitement rather than dread.

Bay Area 2050

Optimism level: too early to tell

Every good planning commission has a long-range plan; this one is the Metropolitan Transportation Commission’s attempt. ↗

As with most long-range plans, this one is very high-level and optimistic about what the Bay Area will look like in 30 years. This means it’s probably not too useful to use as a measure of what will actually happen.

Regardless, there were some interesting tidbits I thought would be worth sharing!

-

The MTC estimates that 20% of vehicles in the Bay Area will be autonomous by 2050. Self-driving technology also has a possibility of appearing in mass transit offerings, like for local shuttles and buses.

-

I was super surprised to see per-mile tolling being floated for nearly all major Bay Area freeways. From a policy perspective this would solve a lot of problems (reducing traffic, reducing emissions, producing $25-50 billion in revenue for transit) but sounds incredibly unrealistic from a public-approval perspective.

-

Maintaining our existing infrastructure is expected to cost $389 billion through 2050, whereas all of the proposed improvements combined are expected to cost less than $200 billion!

footnote: how we can help

Whew, so much stuff is happening! Given how slow transit development moves in the US, I’m pretty sure I won’t need to write another one of these anytime soon 🥲 It’ll be fun to make little follow-up update posts every now and then though.

While it might feel like huge, slow-moving stuff like transit has too much inertia for us to make a difference in, it’s still possible to have a positive impact! Here are some ideas:

-

Go vote!!!! Many transit-friendly measures get brought up for evaluation during elections. But perhaps even more importantly, you can have a direct say in your local officials (like the BART Board of Supervisors) and an indirect say in who appoints transportation-friendly officials (like mayoral positions).

-

Actually use transit! Everyone has a different calculus for how they prefer to go places; try challenging yours— maybe you’ve been making inaccurate assumptions about how fast/convenient/affordable your backup routes are. (For example, after the Caltrain electrification, I’ve found that taking the train is consistently faster and more reliable than driving to work during rush hour— which 100% wasn’t true a few months ago.)

-

If you really want something to be done, chat with your local representatives— or even become one! Here’s a post ↗ about someone in Boston getting a new bus lane. I also recommend Charles Yang’s substack posts ↗ about becoming an organizer for local advocacy.