Foreword

I’ve been tinkering with keyboards for a while now. A couple weeks ago, I’d decided to take upon the challenge of designing and building one from scratch. ↗

I was supposed to have an update for the construction process this week- but I ran into a big question mark: why does every keyboard look and function exactly the same way? All I wanted to do was make one tiny change- replace the standard microcontroller, the ATMega32u4, with a Raspberry Pi- but not only was this more difficult than anticipated, I realized that nobody had ever done this before.

In search of answers, I bought my first nonstandard keyboard: the Iris CE, a split, ortholinear, low-profile device with 25g Choc switches. I’m typing on it right now!

In a vacuum, keyboards like the Iris make so much sense. The non-staggered matrix of keys looks way cleaner, and the lightweight, split layout promises to not give me carpal tunnel by the age of 25.

But the learning curve is insane. I’m two weeks in and I still mistype all the time, because I have to undo the years of muscle memory I’ve built up for a standard keyboard.

Why is a standard keyboard, well, standard? What came before our familiar QWERTY typing machines, and how did they come to be? The answers, as is typical for inquiries like these, were absolutely fascinating- and also completely useless for actually building a keyboard.

Here is my attempt at understanding how and why we got to this point. I dug myself into the depths of a rabbit hole, and now I must crawl back out.

Table of Contents

I. The Pre-Mechanical Era

- Remington No. 1: the first commercial typewriter

- ENIAC and Z3: the first digital computers

- Datapoint 2200: the first personal computer terminal

- Xerox Alto and the Macintosh 128K: the first graphical user interface

II. The Mechanical Era

- IBM Model M: the first mechanical keyboard

- Cherry MX: the renowned keyboard switch

- Kalih, Gateron, Outemu : the evolution from cheap Chinese clones to powerhouse manufacturer trio

- The Groupbuy: a controversial engine for a thriving creator economy

III. The Future

- Towards Open Source: converging on new and better industry standards

- Nonstandard Keyboards: what-ifs turned into reality

IV. The Legacy of the Keyboard

- Parting thoughts

I. The Pre-Mechanical Era

The First Typewriter

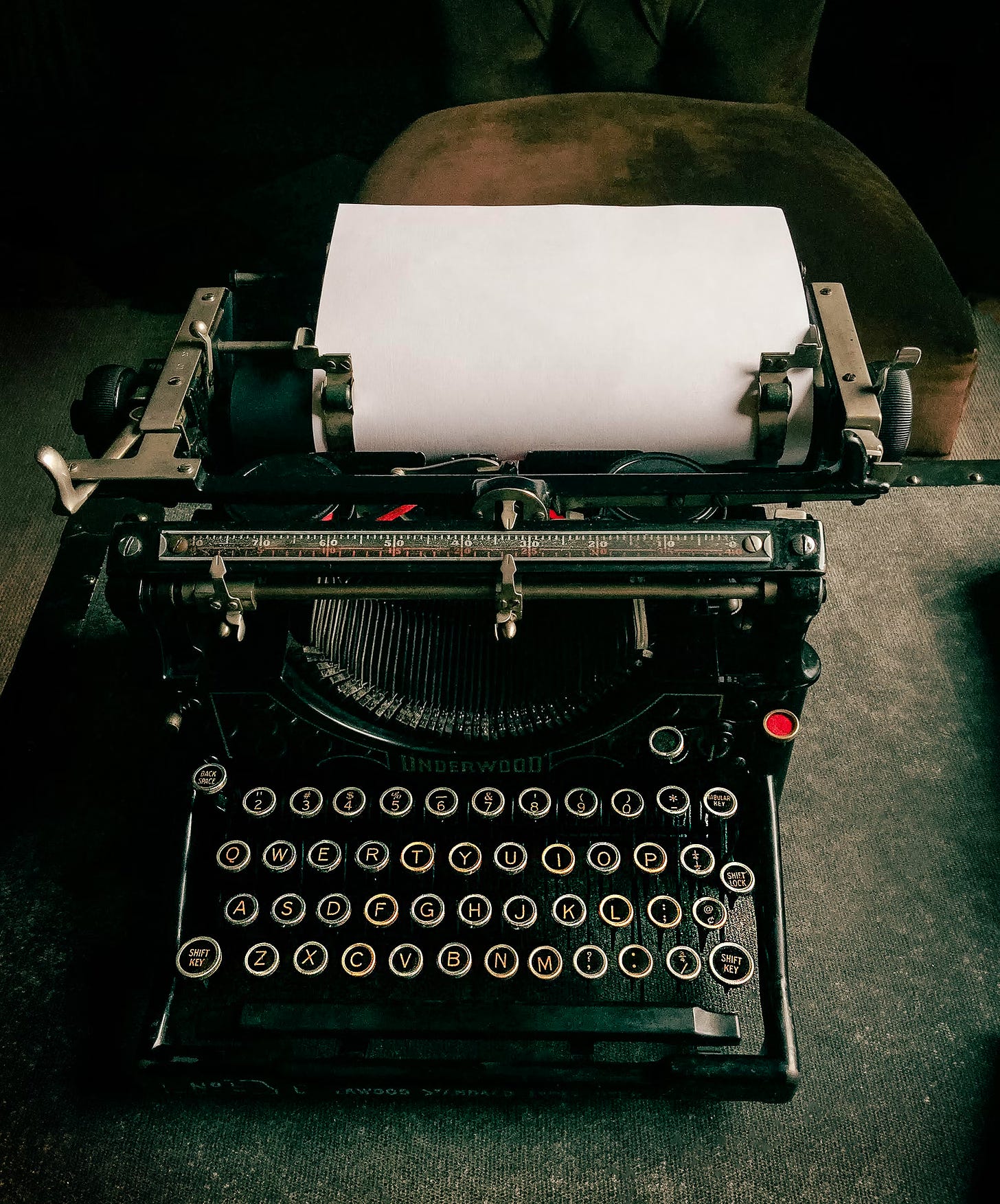

Last week, on July 1, 2024, the world’s first commercially successful typewriter turned 150 years old.

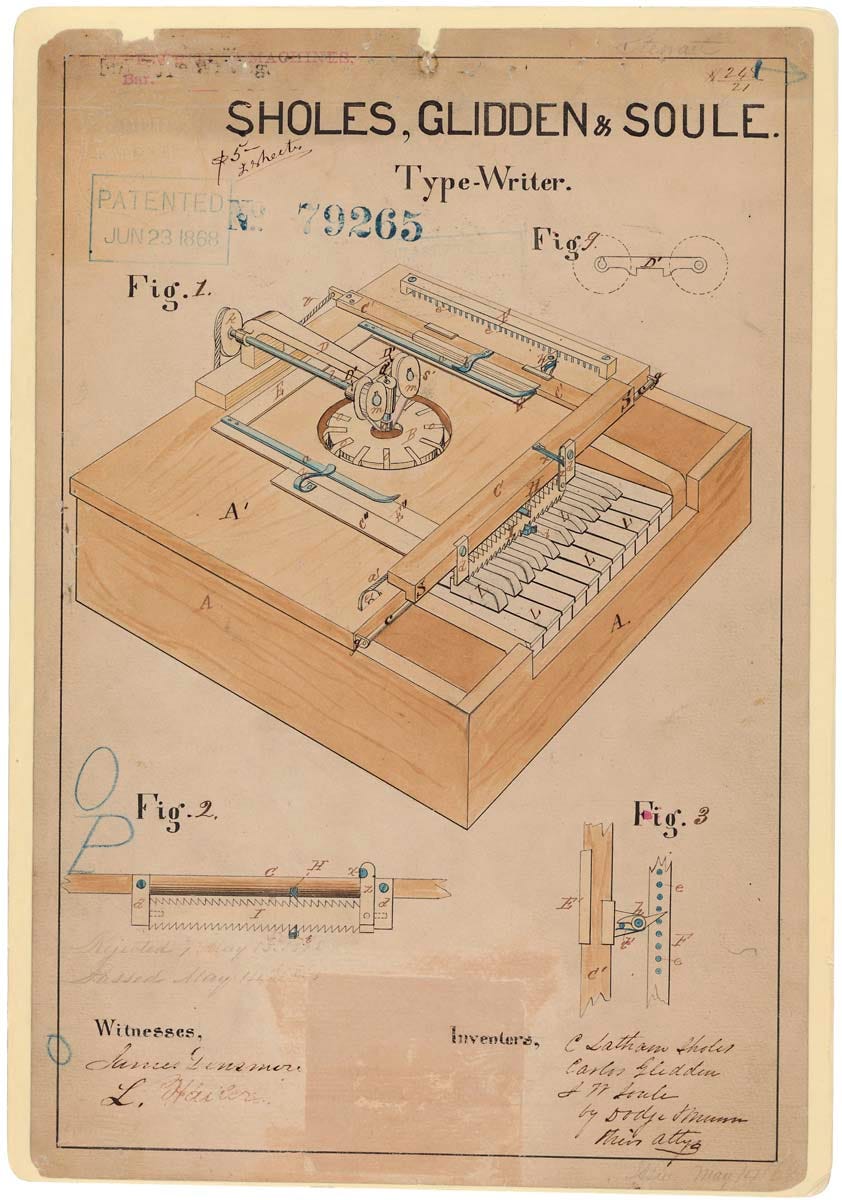

The original patent and early prototypes for the Remington No. 1 looked awfully like a piano. Since a typewriter has to slap a specific letter onto a specific part of the page really hard, this made sense: why not steal a proven, centuries-old mechanism for slapping stuff really hard, but make the hammers output ink instead of sound?

After years of failed prototypes and a change of ownership, The Remington No. 1 was unceremoniously shoved onto shelves. People didn’t want it. Even ignoring the frequent breakdowns and required maintenance, it was 125 whole dollars - a half-year’s worth of income for most! According to this chart ↗ you could get half a two-bedroom house, a horse, or 2500 pounds of cheese for that money.

But as publishers, accountants, and lawyers slowly realized its potential, businesses flocked to the newfangled device. A new industry was born, and the reigning champs got the chance to define the standards that are still in use a century and a half later: the familiar staggered QWERTY layout of uniform, floating keys continues to greet nearly every computer today.

Even though most of the design decisions are vestiges from a past we’ve long left behind, the only thing more powerful than a perfect design is a standard one.

Which came first, the digital computer or the digital keyboard?

Let’s jump ahead a little bit. The year is now 1946; two world wars, Einstein, Turing, and a Great Depression later, typewriters looked almost exactly the same as they did a half century ago. (still no backspace key- that was invented in 1961!). The classic Remington design had prevailed over all others, and something really drastic would have to come to dethrone it.

Sparks of that something were looming across the horizon, as the Digital Age quickly transitioned from a couple loony engineers into a full blown revolution.

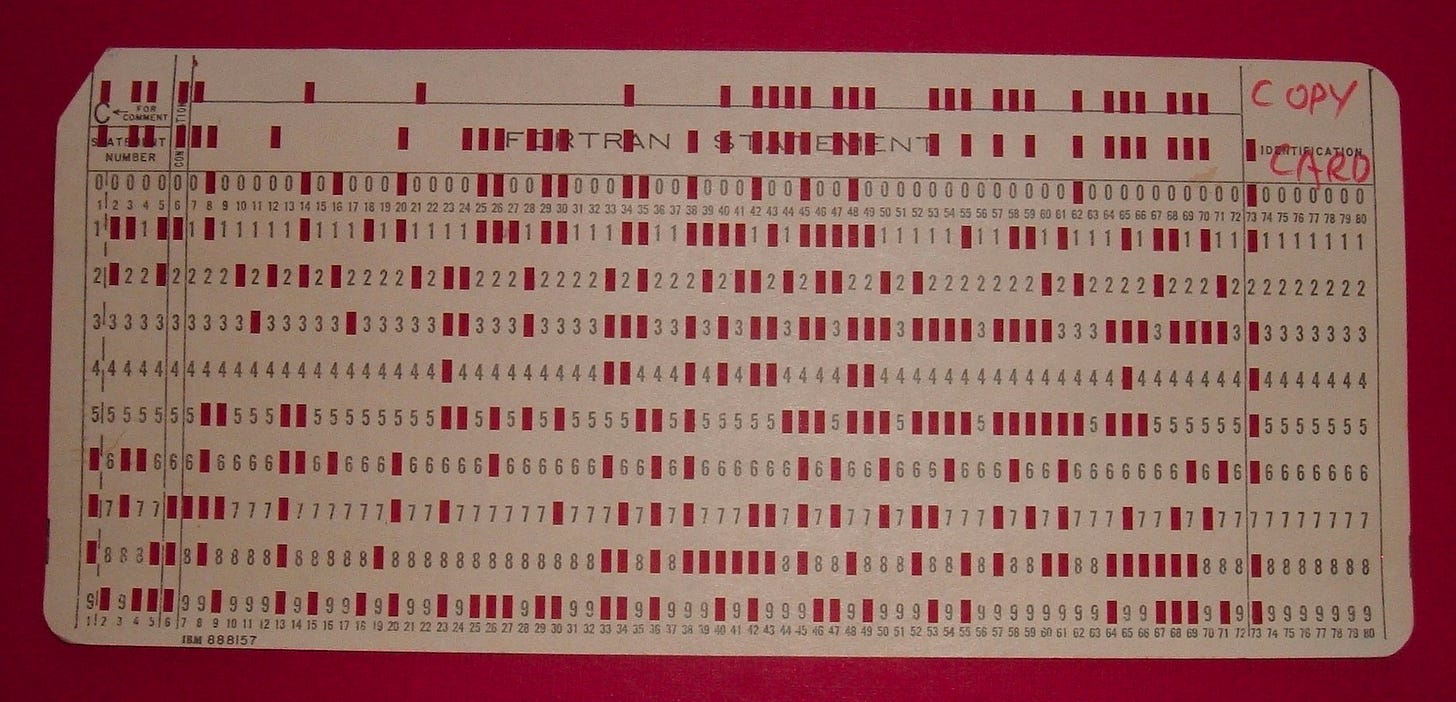

Many historians consider the ENIAC ↗ to be the first modern, programmable digital computer. It didn’t have a keyboard (since it couldn’t understand human text, why bother?). Instead, programmers would create punchcards (like the one below) to feed into the engine for processing.

For now, computers and typewriters were on completely separate branches of the tech tree- but signs of a convergence started to show.

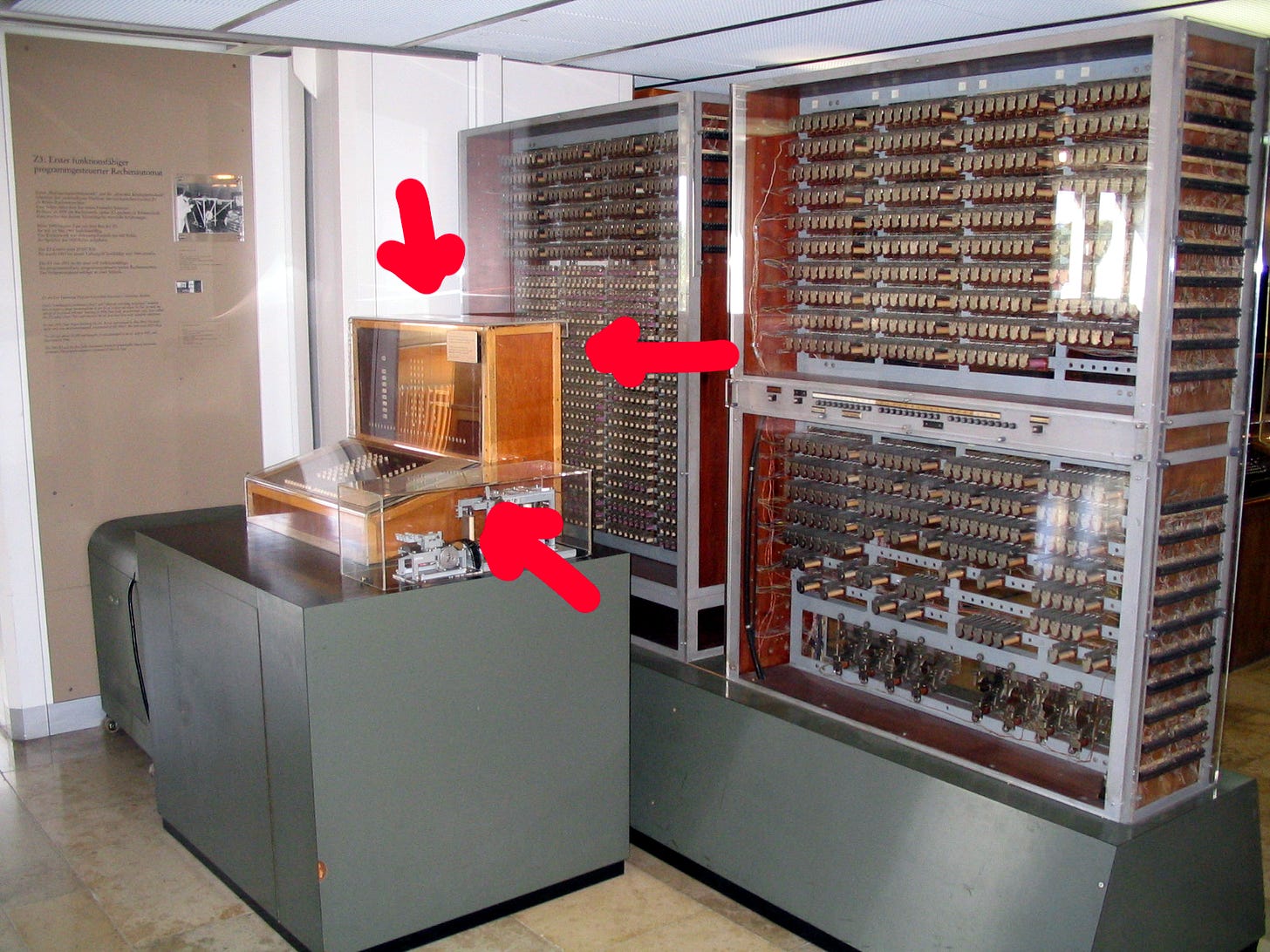

For example, the ENIAC wasn’t really the world’s first digital computer. That would be (with some contention 1) the Z3, which was designed by German engineer Konrad Zuse from 1938 to 1941, four years before the Americans could get to it. And it did have a keyboard!

The Z3’s keyboard may very well be the world’s first digital keyboard. But since the Z3 wasn’t Turing-complete in practice, many argue the ENIAC should get the ‘first’ badge instead.

Was the computer first, or the keyboard first, then? I guess you get to decide :)

Computing for the masses

There was still a ways to go, but these two pioneering designs laid the groundwork for the next big problem: bringing computers to the masses.

After the ENIAC’s pivotal role in Cold War-era military research (like solving thermonuclear equations for the hydrogen bomb), people realized just how powerful digital computers could be, even for normal people.

The invention of the personal computer needed to solve three big technological hurdles:

-

making it cheap

-

making it portable

-

making it easy to use

Moore’s Law meant the first two were a mere matter of time: chip innovation was so rapid that the number of transistors in a CPU doubled every two-ish years, while the price per transistor halved.

The third problem was much more difficult, and called for some truly out-of-the-box thinking.

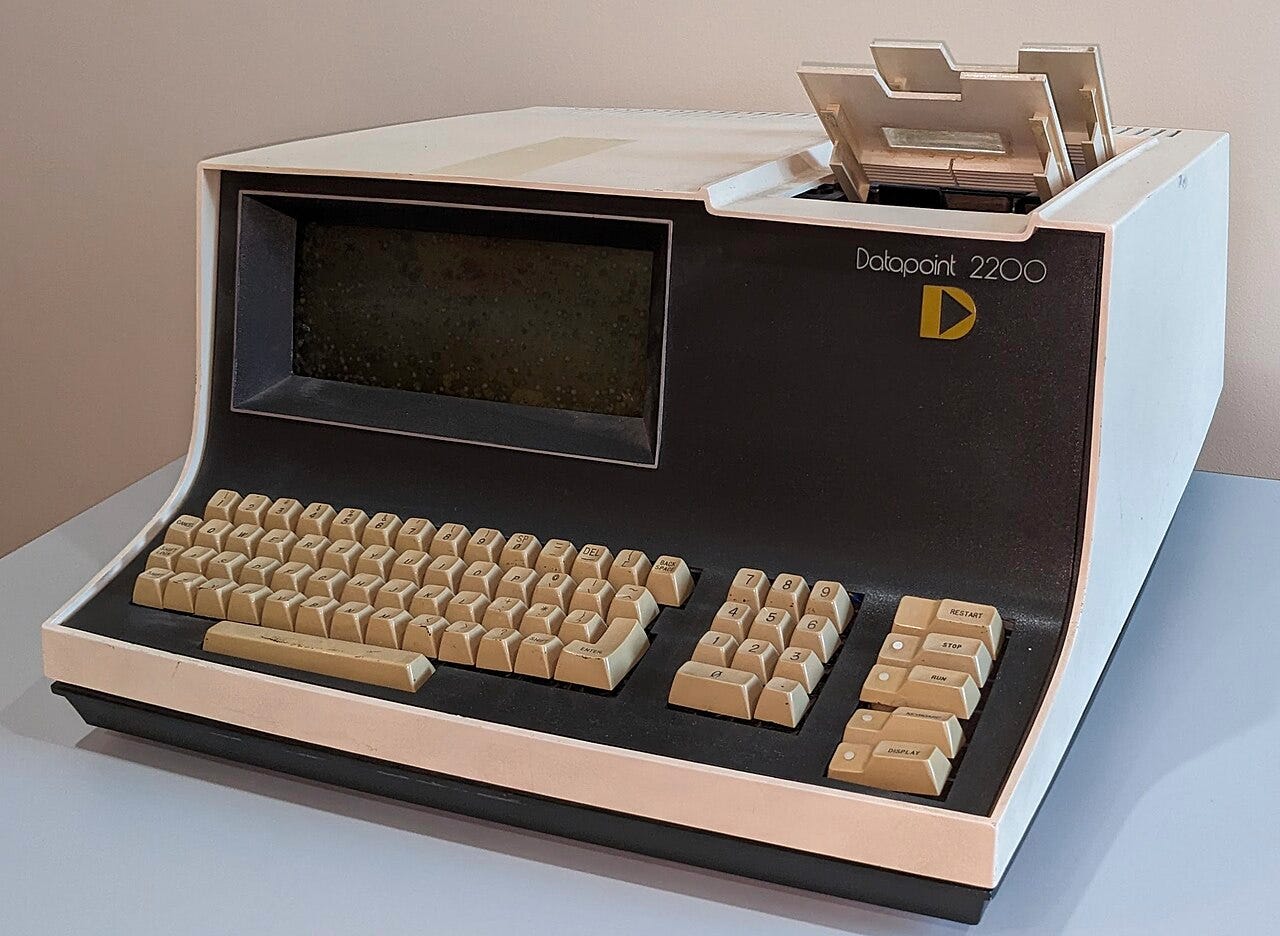

The Datapoint 2200 was the first attempt at a modern desktop PC. It looked like this:

A tiny monocolor terminal, a built-in keyboard, and a tape reader: that was the whole thing. I wouldn’t call it exactly easy to use , but it was a start!

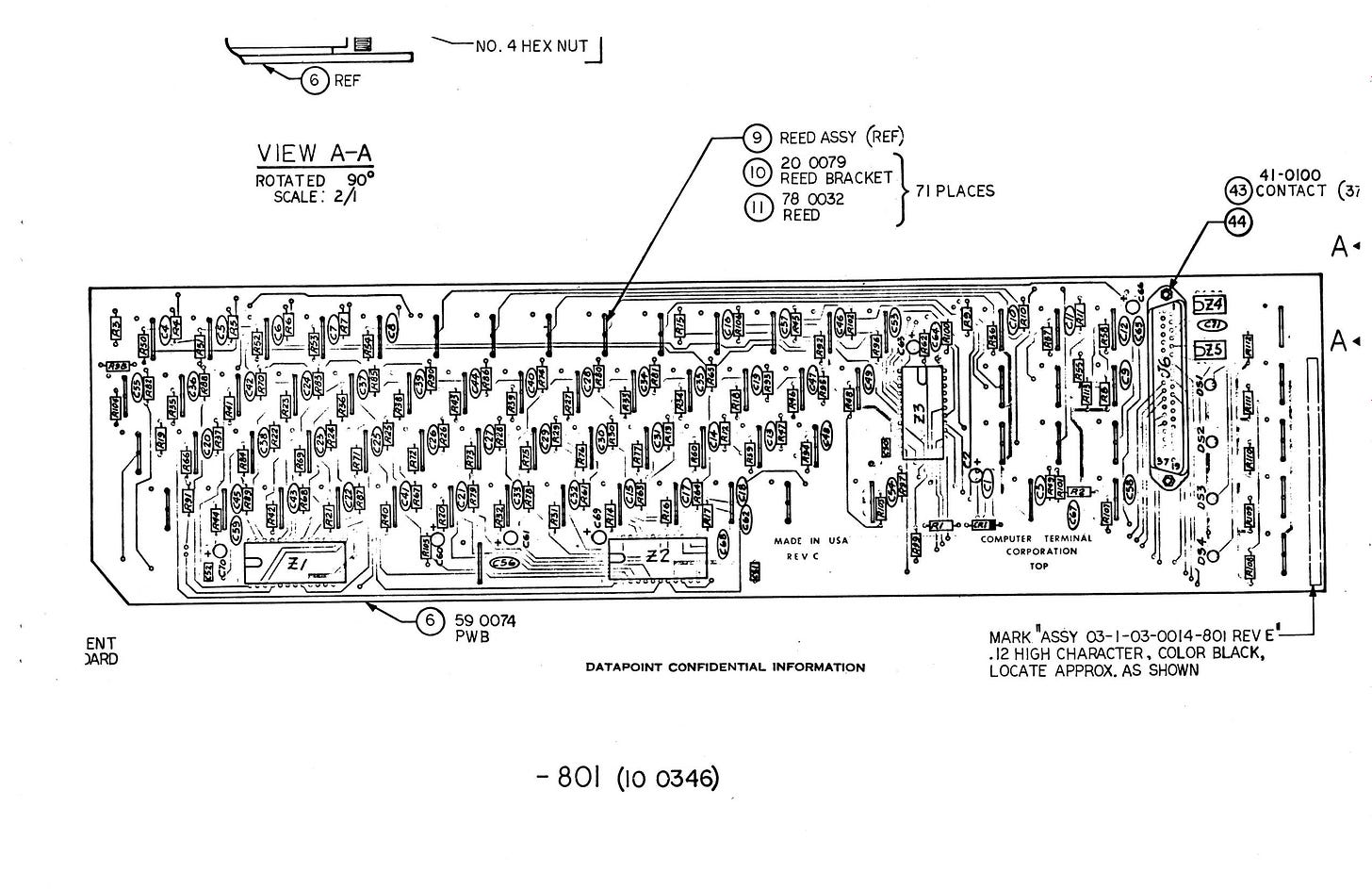

Side note: something that really caught my eye was the schematic for the Datapoint 2200 keyboard:

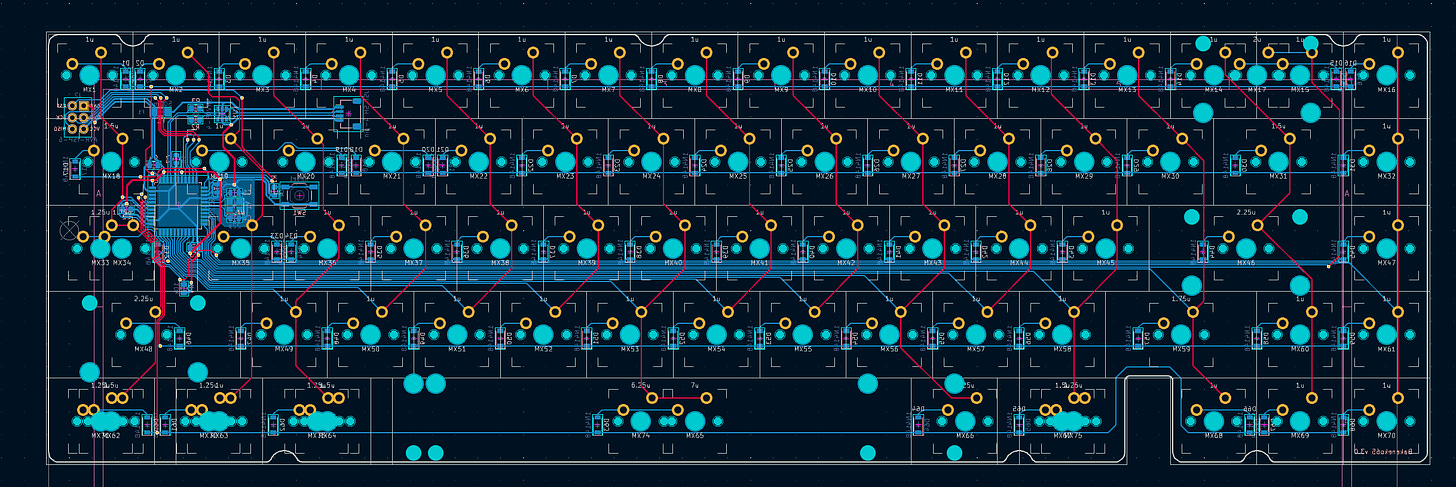

It’s remarkable how similar this looks to a modern keyboard PCB! Below is the schematic for the Bakeneko65 ↗, a popular keyboard kit made by Cannonkeys:

Ever since computers started becoming mainstream, people dreamed of a techno-utopia; the digital world suddenly made what used to be pure fantasy- like holograms and self-driving cars- seem not only possible, but inevitable.

The first step towards bridging the present to our dreams was a better way for humans to interact with computers. The text-only interface of the Datapoint machines was revolutionary in itself, but equally limiting. Shouldn’t we be able to experience computers through images, sounds, and touch, and not just read cryptic text?

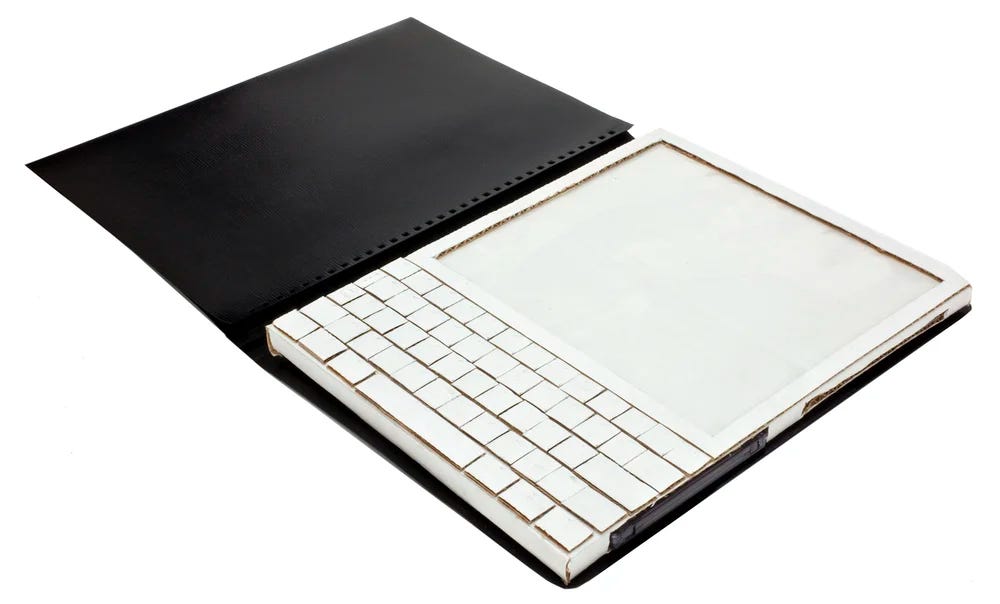

In 1968, Alan Kay did some research on what this step would look like. He made a cardboard mockup of a computer small and thin enough to be held, which would include a video screen and the ability to communicate with other devices through a virtual network. (hey, that sounds familiar!) And it still had a keyboard!

Kay, along with the Palo Alto Research Center, Xerox’s famous R&D lab, set out to actually turn this dream into reality.

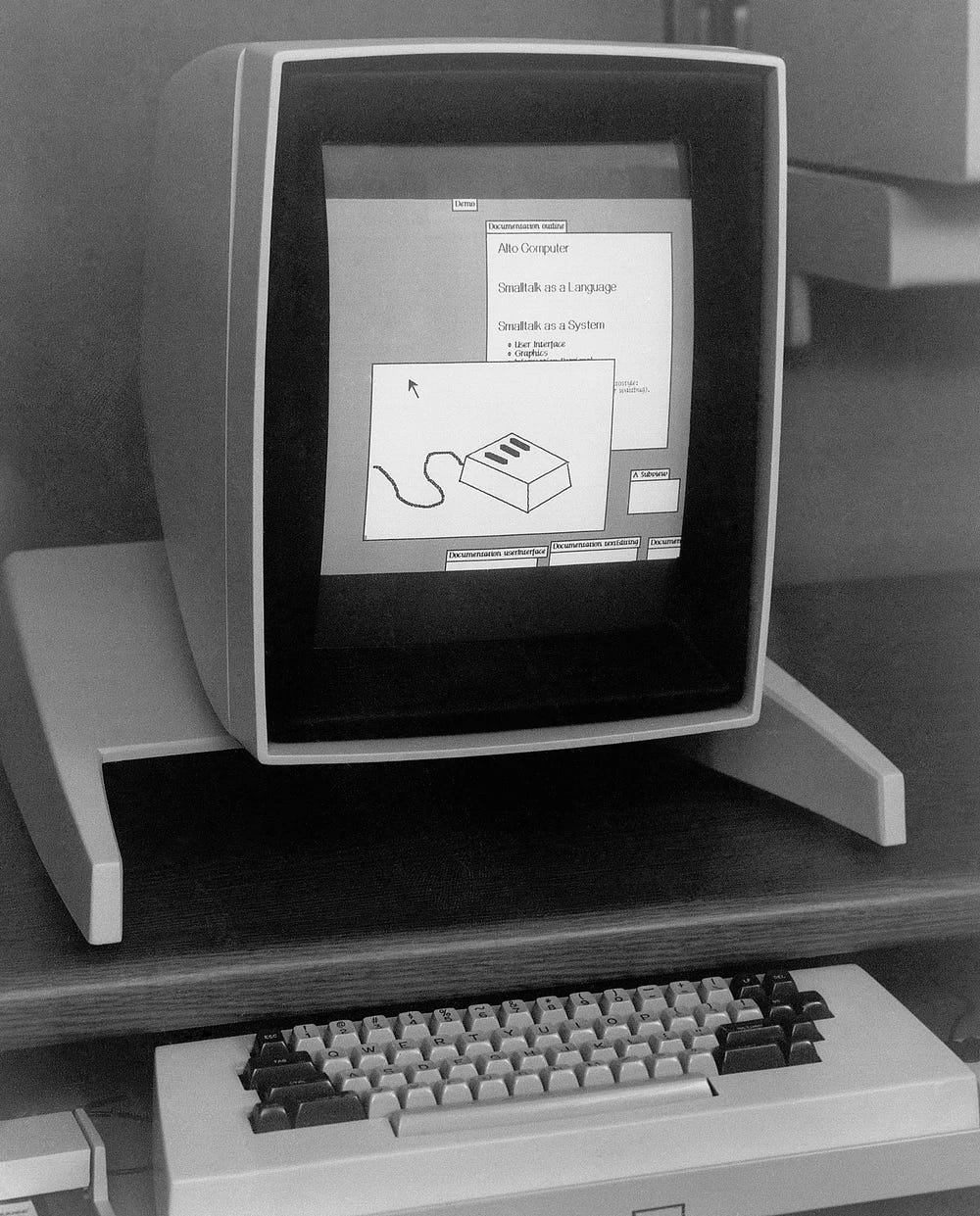

What the PARC team came up with was a “graphical user interface”, in which humans could move a pointer around the screen with a mouse and interact with windows. It came with simple applications like a word processor (which would later become Microsoft Word), a printing application (which would later become the Adobe suite), and an editor for the Smalltalk programming language (which would inspire nearly all modern object-oriented languages, like Java).

The proof-of-concept Xerox Alto was so ahead of its time that nobody knew what to do with it. Nobody, that is, until Steve Jobs entered the scene.

It only took a few years for Apple to release the Lisa (in 1983), and then the Macintosh (in 1984).

From this point on, the keyboard no longer represented the computer itself; rather, it became just one of many plug-in accessories, standing alongside mouses, speakers, and microphones as a necessary part of the whole to drive the newly-popularized graphical interface.

And with that shift, a new hobby was born: one of infinite customizability, built around the promise of ultimate utility.

II. The Mechanical Era

The IBM Model M

While Apple was busy inventing their new GUI, IBM strode on with confidence. As the leading PC manufacturer, they hardly cared about the scrappy startups around them (like Microsoft, another small company who’d just come out with the MS-DOS and was cooking up their own GUI, called Windows).

Facing massive consumer demand for durable, premium keyboards for their popular terminals, they set out to design the ultimate typing experience.

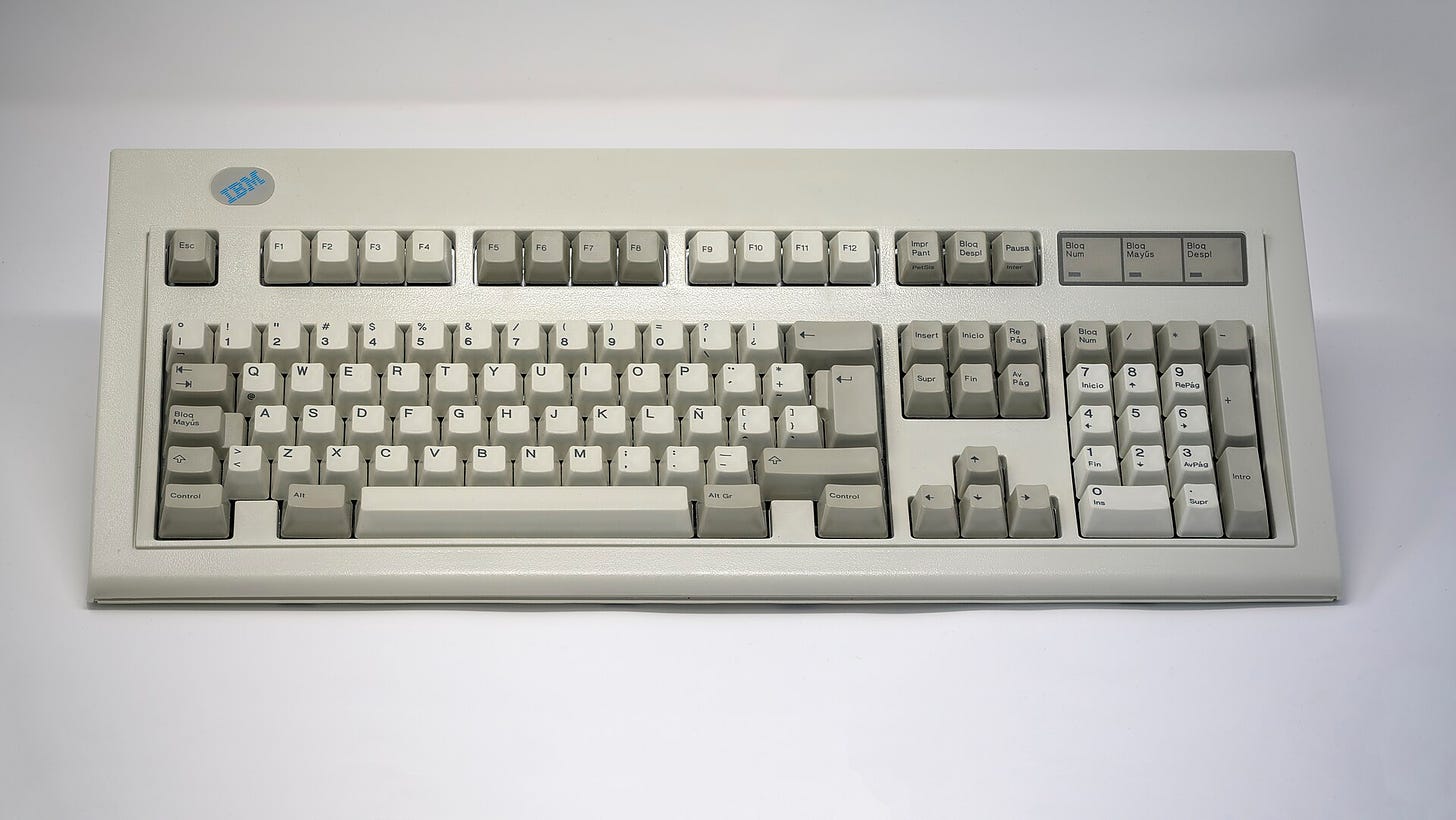

In 1985, IBM came out with the most legendary keyboard in history: the Model M.

The Model M was immediately noticed for several reasons.

First, people loved its layout so much that it became the de-facto standard. Today, that standard is officially known as the ISO and ANSI layouts, which almost all modern keyboards use.

Second, its unique buckling spring switches were fun to type on and basically indestructible. You can go on eBay right now and find hundreds of fully functioning original Model M’s from the 1980s. (I cannot emphasize enough how impossible it is to make an electrical component last 40+ years with no sign of decay.)

Many people consider the Model M to be the first mainstream mechanical keyboard , meaning that each switch had individual, moving parts that sent a signal when they made contact. This marked a departure from the prevailing membrane design (how nearly every keyboard is still made today), which was a lot simpler and cheaper to produce.

Although the Model M wasn’t the very first mechanical keyboard it represented a massive turning point: it got people to start caring about the keyboard they were using. What was seen before as a standard, boring computer part was now exciting, innovative, and noteworthy.

Cherry MX rises to the top

Computer users weren’t the only ones who paid attention to the success of Model M; other companies also stepped in to try and captivate the fledgling market.

One of these companies was the German manufacturer Cherry, which had been making keyboard switches and other various mechanical parts for decades to moderate success.

(here’s someone clicking a Cherry switch from 1959.)

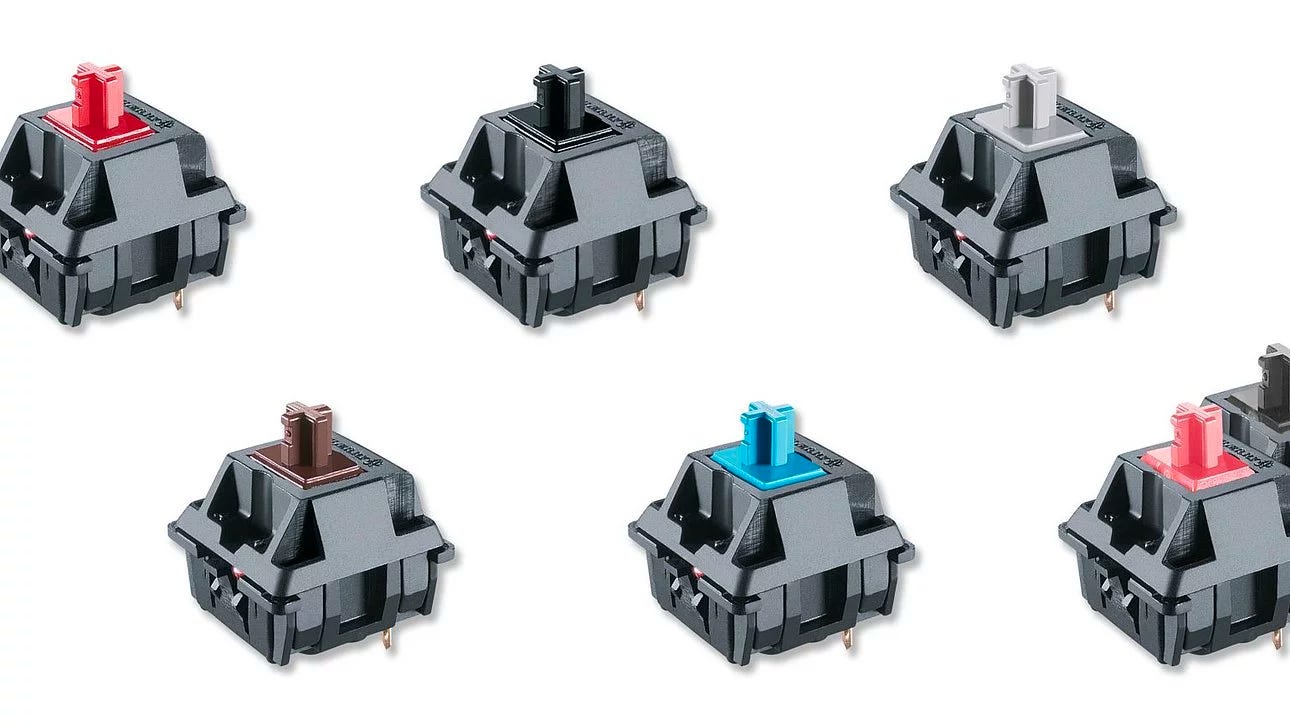

In 1983, Cherry’s latest experiment was a series of standardized, modular switches. They coined it “Cherry Mechanical X-Point Technology”- Cherry MX for short.

The Cherry MX lineup quickly gained traction: they felt just as good as the Model M’s, and were just as durable, with each switch rigorously tested and certified for a lifetime of 100 million actuations.

A big selling point of MX switches was their customizability. They offered three main types, which each had a different color switch:

-

Linear switches (Black, Red) are smooth, with a similar amount of resistance throughout the entire press.

-

Tactile switches (Brown) are bumpy: it’s very clear when the key gets actuated, since you feel a noticeable amount of resistance about halfway down.

-

Clicky switches (Blue, Green) are like tactile switches, but have an extra moving piece that makes a crispy, loud click sound when you go past the bump.

Cherry MX is yet another keyboard standard that got so popular that it persists to this day. Many people still consider Cherry switches to be the ultimate gold standard, with every other switch manufacturer producing “Cherry MX-compatible” switches.

Nearly every mechanical keyboard today supports any MX-type switch, and some even let you hotswap between switches by simply pulling them out and plopping in new ones.

Together with the Model M, Cherry defined an entire industry. When someone says “mechanical keyboard” today, there’s a 90 percent chance you can automatically assume it’s MX-compatible, with an ANSI or ISO layout.

Kalih, Gateron, and Outemu: the resurgence of enthusiast keyboards

As computers became increasingly popular over the 90’s and early 2000’s, mechanical keyboards slowly faded away from the mainstream. Even though there was always a devoted group of keyboard enthusiasts, more and more new computer users just wanted something that worked.

But one phenomenon almost singlehandedly brought back the mechanical keyboard into the popular tech space: PC gaming.

Going into the new millennium, computers were more powerful than ever and could finally keep up with the technological prowess of gaming consoles like the Nintendo 64 and Sega Genesis. Smash hit titles like Doom, Halo, and Starcraft had gamers flocking back to their PC’s. And just like the typing enthusiasts of the 80’s, they once again demanded durable, satisfying keyboards that could keep up with their fanatic button mashing.

Now that the standards had all been agreed upon, manufacturers around the world scrambled to innovate around Cherry, undercutting them with cheaper alternatives.

During this time, three big players popped up: Kalih in 1990, Gateron in 2000, then Outemu in 2004- all based in China. With their much lower production costs compared to Cherry’s German factories, they pumped out billions of Cherry clone switches for a fraction of the price.

Most of the earlier clone switches were absolutely terrible. Users complained about the poor quality control and low durability; some weren’t even mechanical at all- just a cheap membrane dome disguised within a plastic Cherry MX case! (I was the not-so-proud owner of one for a while…)

But over the years, they found their stride, partnering with well-known designers from companies like Razer as well as knowledgeable keyboard hobbyists to create hundreds of high-quality, unique switches.

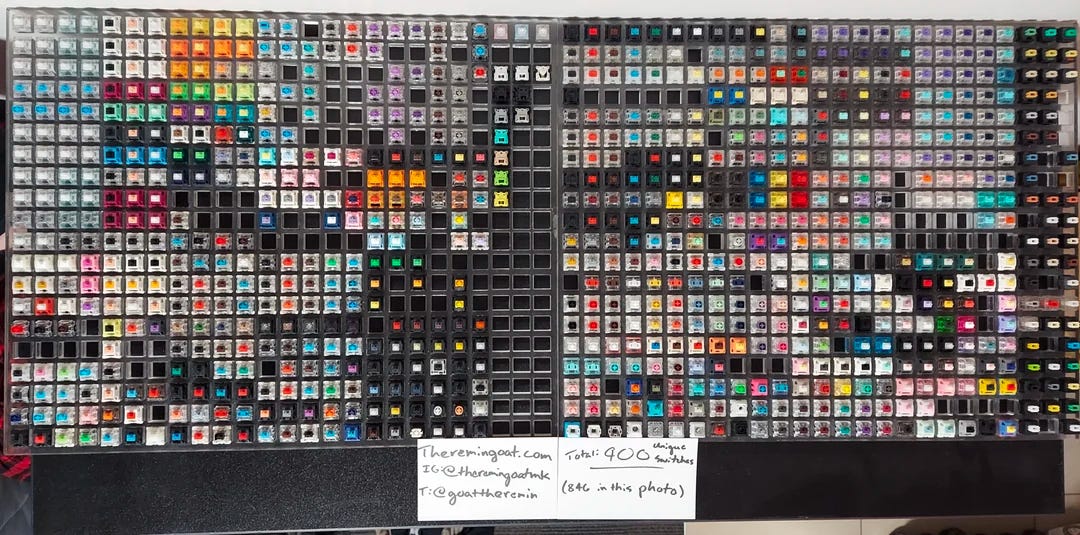

Today, nearly every mechanical switch on the market is manufactured by one of these three companies. Some of the most famous ones include:

-

The Boba U4 and U4T, widely regarded as the best tactile switches ever produced due to their tight tolerances and distinctive bump. Designed by Gazzew, manufactured by Outemu.

-

The Holy Panda series, first debuted as a “frankenswitch” of a Halo switch stem with a Invyr Panda case, now designed by Drop and manufactured by Kalih.

-

The Zealio and other ZealPC switches, which are the most expensive mass-produced switches available, ranging from $1 to $1.50 each. (For reference, an original Cherry MX costs around 25 cents, and the Boba U4 costs 65 cents.) Designed by ZealPC, manufactured by Gateron.

The Groupbuy

Keyboard people are very particular about their keyboards.

With the explosion of choice comes decision paralysis: what’s your favorite switch? how many keys do you want? do you like something light and portable, or something with satisfying heft?

For the wealthy (or the enjoyers of crippling credit card debt), the answer is usually “yes, I want all of it.” And so they shall:

Another enterprising crowd of enthusiasts noticed two things:

-

Their perfect keyboard doesn’t exist yet (and they want it really badly).

-

A lot of people (see above) are willing and able to pay a lot of money to buy yet another cool keyboard for their collection.

Slowly, a thriving creator economy sprouted up to facilitate a symbiotic relationship between buyers and sellers. Today, this economy sprawls over a vast network of vaguely connected internet forums, Discord server, and Shopify storefronts.

To explore further, let’s look at the journey of a real keyboard in the wild: the Alpine65.

Step 1: The Interest Check

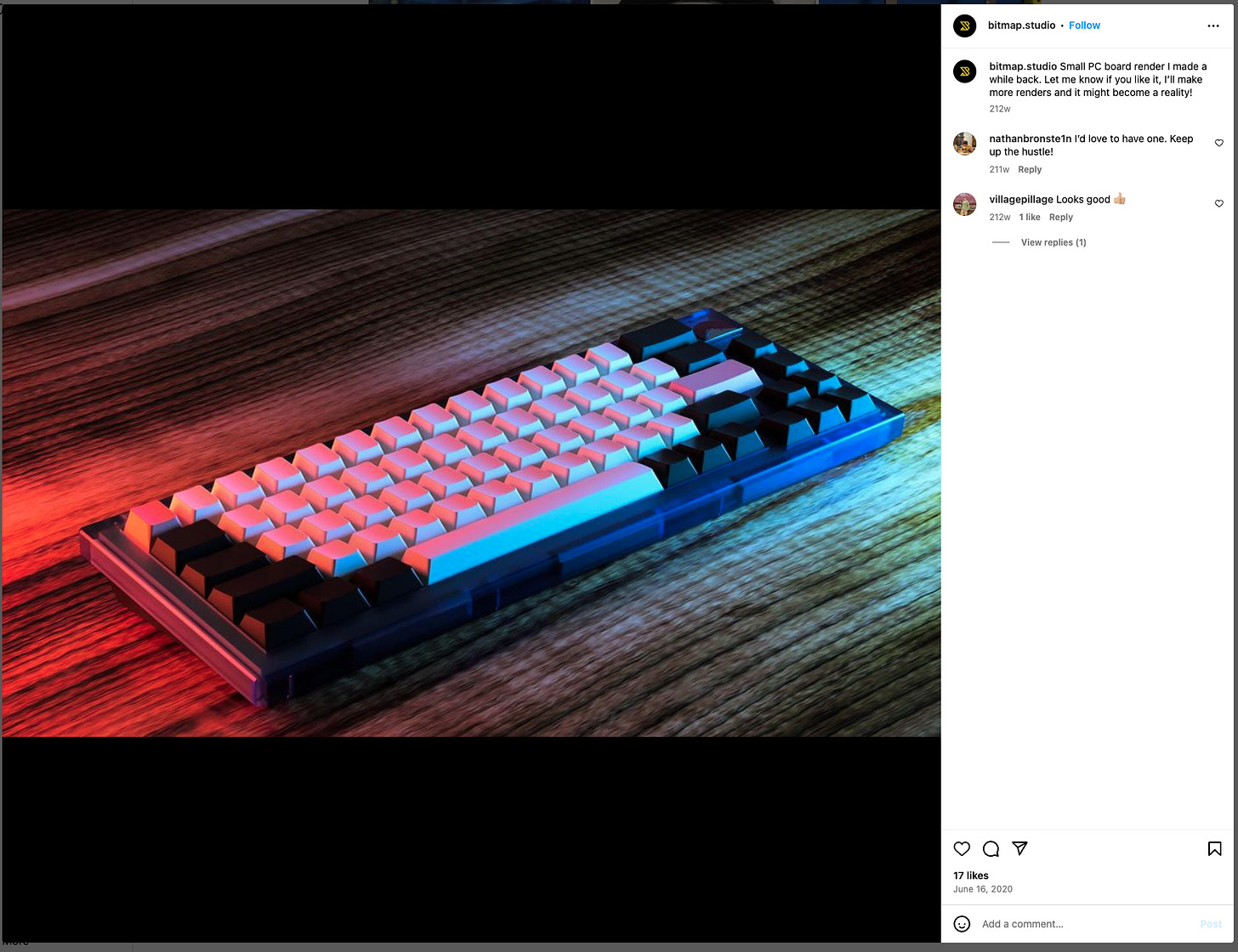

In 2020, Alex wanted to make a keyboard. Alex founds Bitmap Studio, and makes an aspirational Instagram post with a 3D render of their dream keyboard:

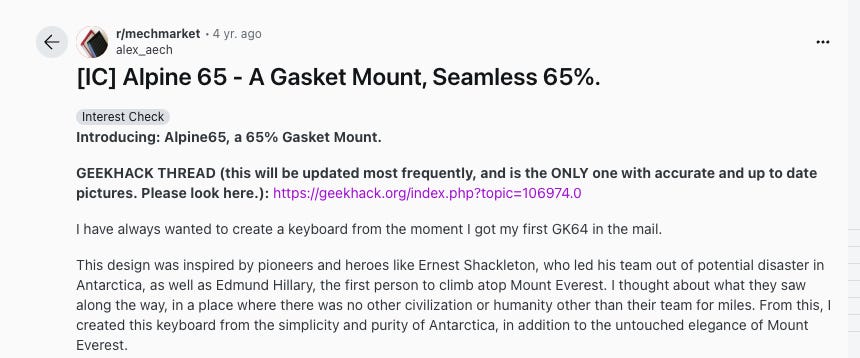

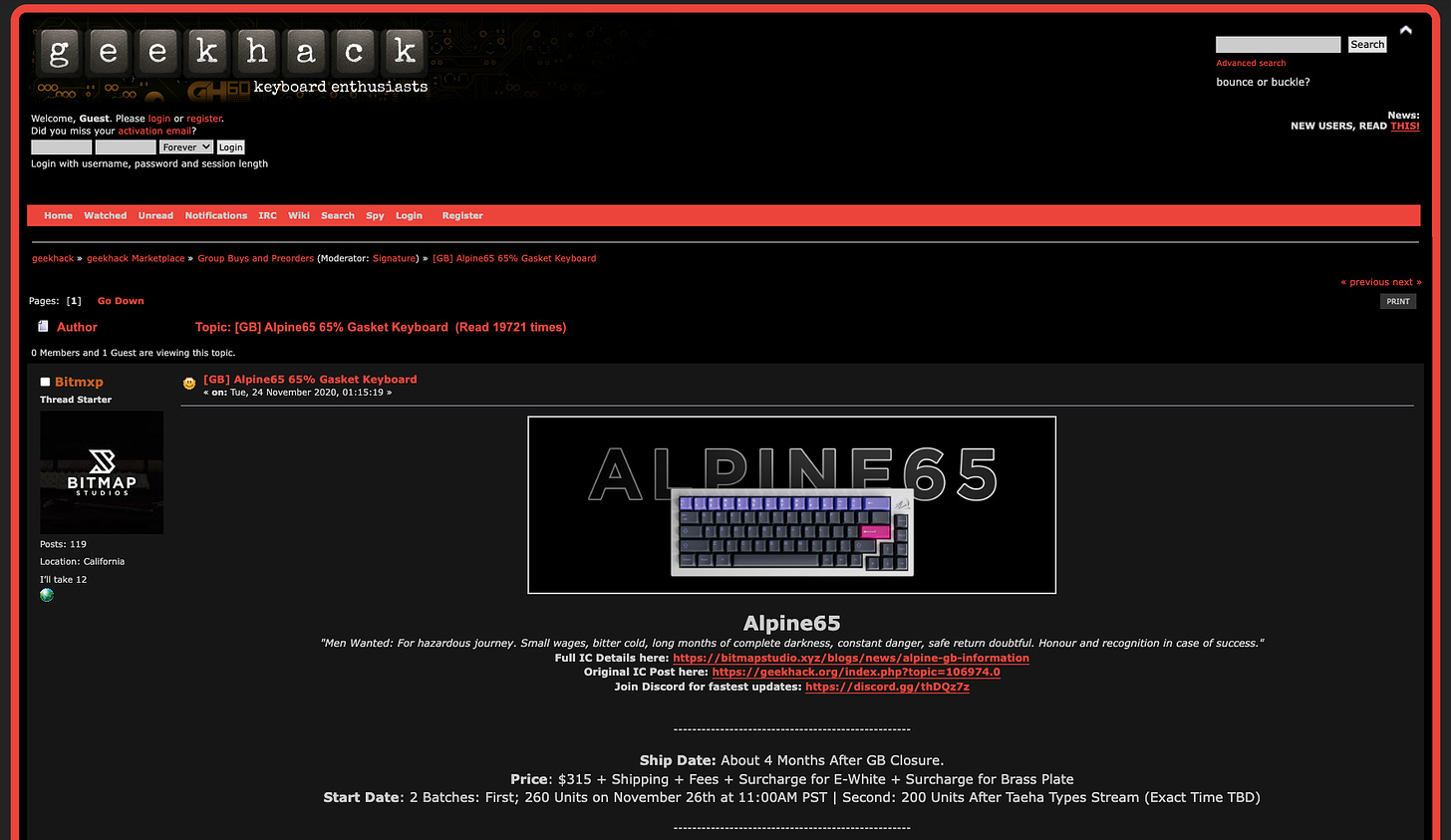

Alex posts the keyboard onto Reddit and Geekhack (the most popular forum for keyboard things).

In the keyboard community, these types of posts are officially known as Interest Checks, or IC’s. The main purpose of IC’s is to gauge how excited the community is for a particular project, so the creator knows if there’s enough buy-in to move onto prototyping.

In the Alpine65’s case, a lot of people were interested. To date, over 160,000 people viewed the Geekhack post ↗!

The virtual buy-in was more than enough for the newly formed Bitmap Studio to scrape some prototypes together.

Step 2: The Group Buy

As nontrivial as designing and building a prototype from scratch is, it’s small potatoes compared to the real challenge: going to mass production.

Manufacturing several hundred keyboards takes an enormous amount of upfront cost: building them to order would be far too inefficient, so factories will take the design, set up the assembly line, and make them all together.

The keyboard community devised another trick to get around this: the Group Buy (GB).

In Group Buys, hungry enthusiasts will happily drop hundreds or even thousands of dollars on a nonexistent keyboard, in exchange for an “IOU” from the creator to ship one over in a few months to years, when (or if) the keyboard is finally produced. Some more limited-run group buys even run lotteries, where the winners have the chance to buy said nonexistent keyboard! Sounds fantastic, doesn’t it?

But group buys are a necessary evil: they’re the Kickstarter of the keyboard world, injecting the much-needed capital for creators to be able to create the keyboard and place the order in the first place. Some projects fail, leaving buyers with nothing to show for their investment; most make it out of development hell (eventually).

Step 3: In Stock

Oftentimes, creators will order a bunch of extra keyboards and sell them to vendors who run online keyboard stores (like CannonKeys ↗ in the US, CandyKeys ↗ in the EU, PantheonKeys ↗ in Singapore, etc). It’s a great chance to make a great keyboard available to a much wider (and possibly international) market.

When this happens, a keyboard becomes “in stock”, meaning it’s already produced, sitting in the warehouse, and ready to ship the moment you click on the ‘buy’ button.

Sometimes, the creators themselves will open up a store of their own- here’s bitmapstudio.xyz ↗ for example. Now that Shopify exists, this is surprisingly easy to do!

Step 4: mechmarket

When almost every purchase is a preorder, not everyone can be a happy customer. Many people, after waiting years on a forgotten groupbuy, no longer want it when it arrives; some others look to trade their now-super-exclusive collectibles for much higher than the asking price (though this practice is highly contentious).

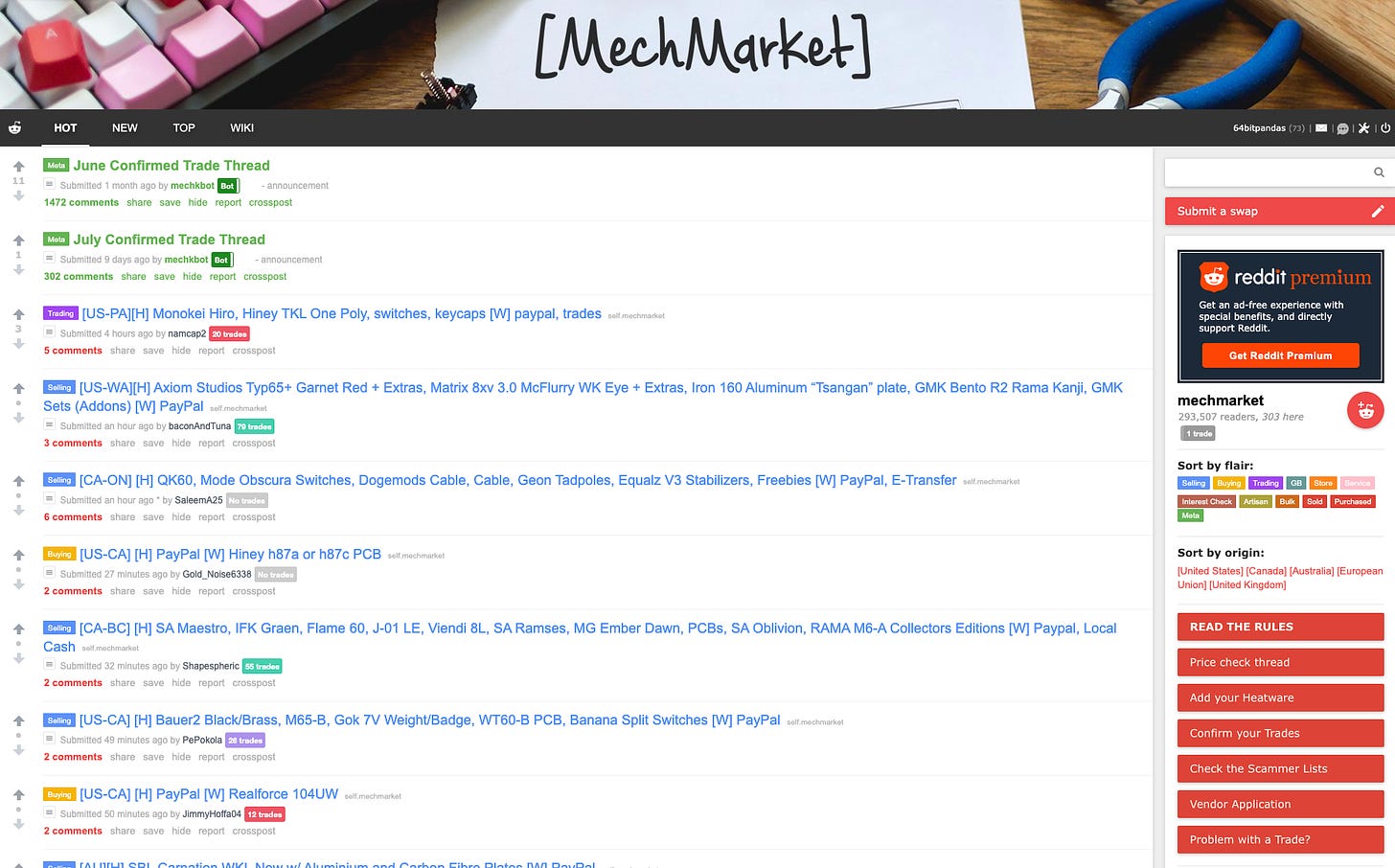

In the Reddit forum r/mechmarket ↗ you can find anything and everything to do with keyboards, from handmade artisan keycaps to flea market grab bags of unwanted switches. This is the eBay of keyboards: a marketplace to sell whatever you don’t need, and impulse buy at your heart’s desire.

III. The Future

As people are spending more and more time on their computers, the demand for enthusiast-grade keyboards is at an all-time high. That means innovation is at an all time high, too! Here are some exciting developments that I’m looking forward to experiencing in the near future.

Towards Open Source

Many creators are less concerned about money or profit, and more about simply sharing their love and knowledge of the craft to as many people as possible.

They’ve released all of their designs to the public, often with instructions on how someone might be able to recreate them with basic tools and a few spare dollars. Here’s one compilation of open source keyboard designs. ↗

Keyboards aren’t only a pure hardware creation; they need firmware to convert key presses into something your computer can understand, either through USB or Bluetooth.

Nearly every modern keyboard comes with a built-in microcontroller, which is a very low powered processor that runs basic software to perform this conversion.

For most of keyboard history, manufacturers would make this firmware in-house, which makes it hard to do things like customize key bindings, create macros, or manage the keyboard’s backlight.

Recently, though, the open source QMK firmware ↗ is taking over the world. Nearly every keyboard kit today is QMK-compatible, which allows users to use a single, familiar interface (like VIA ↗) to customize all their keyboards.

Nonstandard Keyboards

Now that there’s no longer a physical limitation on keyboard layout, creators are branching out to wacky experimentation. Some of it is practical (like ergonomic keyboards); most of it is purely for fun (like knobs and LED screens).

Ultra-compact keyboards

Some crazy people want their keyboards to be as small as possible for some reason. This led to the 40% keyboard standard, which has 40 keys as the name suggests. This means no function keys, no numpad, no number row, and no arrow keys!

In order to make up for the missing keys, such keyboards come with mappable function layers, so you can press one or more function keys to access an alternate set of key bindings.

Split keyboards

It’s no secret that typing on a keyboard all day can be pretty terrible for your wrists.

In order to resolve this, some people tout the power of split keyboards, in which the two halves of the keyboard can come apart and be typed on at whatever position is most comfortable.

Low profile keyboards

One problem with the Cherry MX standard is that MX switches are quite tall- much taller than the laptop keyboards many people are used to.

New standards, like the Kalih Choc switch, are coalescing around a subgroup of people who like mechanical keyboards, but appreciate the sleekness of non-mechanical keyboards.

Ortholinear keyboards

Since keys can be arranged however we want now, there’s really no requirement to keep the stagger. Ortholinear keyboards are shaped in a simple grid pattern, kind of like how 8-year-old me would draw computer keyboards for a school assignment. They’re very elegant, but come with a learning curve since the keys are all in different positions from how we’re used to.

Macropads

Some keyboards aren’t even meant to be typed on! For those who need extra keys (for streaming, or Photoshop, or video games), macropads come with a small collection of customizable keys. Alongside scripting languages like AutoHotkey ↗, these switches can be made to do pretty much anything.

IV. The Legacy of the Keyboard

We’re currently living the legacy of the computer keyboard: will the gold standard continue for another 150 years, or will something change tomorrow? I’m betting on the former.

When the iPhone was first revealed in 2007, we thought keyboards would go digital. When Siri came out, we thought we’d never have to type again.

But even now, the keyboard is still vital for everything we do. We use keyboards to converse with ChatGPT; we still have staggered QWERTY on smartphones; even in VR, we have to mess around with a floating keyboard. Despite the game changing innovations in human-computer interaction over the last decade, we can’t seem to erase the century-and-a-half of design precedent, however arbitrary it is now.

I wonder what Sholes & Co. would think if they saw a modern keyboard. Would they be surprised? proud? disappointed?

As for me, I’m just here to see how far this niche can go. I’m on a keyboard for 8+ hours a day, so why not make it a fun experience?