In my second semester of college, I took a class on the philosophy of science. ↗ The premise of this class sounds contradictory on first glance: aren’t philosophy and science two opposing forces, for very different types of questions?

Science strives to be objective and value-free. ↗ Regardless of who’s conducting experiments or making observations, a scientific truth should always be consistent, measurable, and statistically significant.

While also built atop logic and rationality, philosophy is neither objective nor value-free. Many philosophers even argue that it’s impossible to reach this ideal, since we’re unavoidably influenced by our biases and past experiences. Unlike with science, it’s possible for many conflicting answers to arise from a single problem and be equally valid.

There are a lot of philosophical questions that are impossible for current scientific methods to even scratch, like:

- Why do we exist?

- What is consciousness?

- What is the meaning of life?

As science grows ever more capable and nuanced, the line between philosophy and science starts to blur. We’ve unlocked pretty compelling answers to things we once thought were unsolvable:

- Why are there seasons?

- What are we (physically) made of?

- Why do we remember some things, but forget other more important things?

This brings us to one such question stuck in the middle of that blurry line:

What makes humans unique?

intelligence?

NEW YORK — The big trouble, in Kurt Vonnegut’s view, is our big brains.

“Our brains are much too large,” Vonnegut said. “We are much too busy. Our brains have proved to be terribly destructive.”

Big brains, Vonnegut said, invent nuclear weapons. Big brains terrify the planet into worrying about when those weapons will be used. Big brains are restless. Big brains demand constant amusement.

—Los Angeles Times, October 23, 1985 ↗

It’s the beginning of March 2020. At the same time I’ve been struggling to wrap my head around the Philosophy of Science, I’m also taking a class on anthropology, and I’m tasked with writing a paper relating the themes of Kurt Vonnegut’s Galapagos to evolutionary biology.

I’m very glad I finished it early, on March 12— four days before the COVID-19 lockdown ↗ and the chaotic upheaval of society— or else the existence of Galapagos would have been erased entirely from my memory.

Vonnegut’s main argument in Galapagos is that our big brains are no longer sustainable from an evolutionary perspective. If only we didn’t have the urge to be different and special , and just took the cue from literally every other species on the planet to thrive in blissful ignorance…

Galapagos is satire, like many of Vonnegut’s other great classics. He does raise a good point though- intelligence is relative, and by a lot of measures we’re not even that good at it.

When facing existential questions about human nature, an anthropologist will point out that we’re really not that different from our hominid ancestors or chimpanzee cousins. Most of our behaviors are vestiges of an evolutionary past that we’re getting close to reconstructing- and once we do, maybe we have a shot at understanding ourselves.

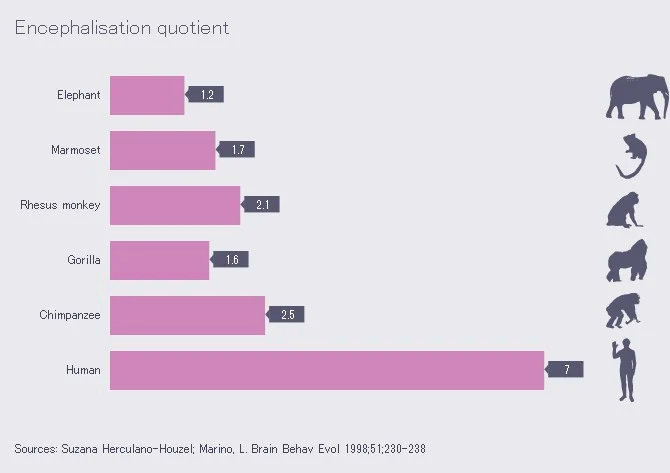

One measure that anthropologists use as a heuristic for intelligence is encephalization , or the presence of an abnormally high ratio of brain mass to body mass. Humans are the most encephalized of all known species, with a brain-to-body-mass ratio 6-7 times greater than the typical mammal.

From a scientific perspective, Vonnegut is actually right. Studies ↗ show ↗ that more encephalized species are more at risk of extinction. Researchers hypothesize that the extra energy needed to fuel complex, hungry brains often outweigh the benefits they provide. Humans, of course, are the clear exception to this trend.

So, maybe our big brains do make us unique, but not in a way that would immediately spell out the success of our species.

theory of mind?

< Maybe we’re the fools, for thinking we know things. Maybe humans are the only ones who can deal with the fact that nothing can ever be known at all.>

—Orson Scott Card, Xenocide

A common trope in science fiction is one where aliens possess a collective mind, shared by all beings of a species. They struggle to understand human individualism and all of the irrationality that comes with it: why shroud oneself with secrets, or lies, or mystery when everyone can know everything all the time?

Despite all the war and conflict it brings, our individuality is an undeniable part of what makes us human. If we all shared one mind, there would be no need to write; to express ourselves through art and music; or to share our stories around campfires and bars. There would be no competition; no cultural distinctions; no concept of personality.

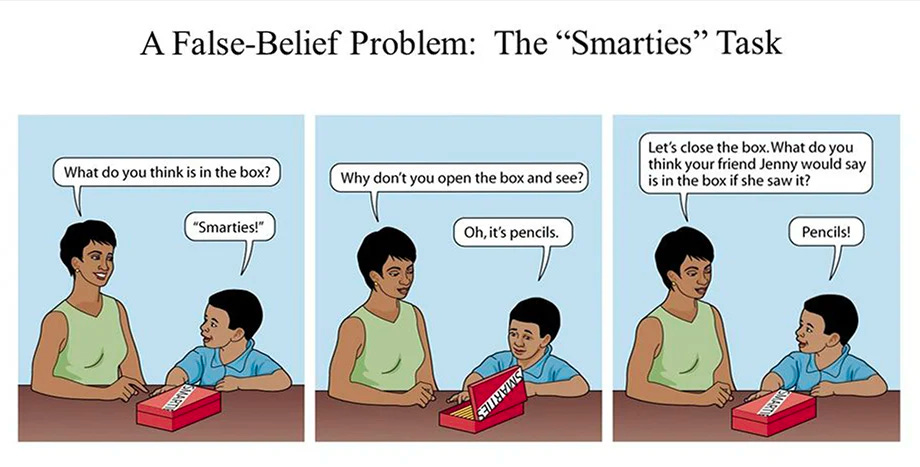

The key that makes all of this work is what psychologists call theory of mind: our ability to respect other humans as intelligent beings with their own agency and unique mental representation of the world.

Put succinctly, I know you know things I don’t know. I also know you know I know things you don’t know. Makes sense? Great!

We weren’t sure if other animals also understood theory of mind, so some researchers went over to Africa and found a couple monkeys to interview in exchange for bananas.

It turns out, monkeys are a lot harder to interview than humans. For one, they can’t speak to us; and even if they could, they usually don’t care enough to give us the answers we want.

As such, we’re still not completely sure about the extent to which other species possess theory of mind, and it’ll be exciting to see what research comes out in the next few years. We do know at least, though, that they can definitely express abilities similar to a 2 to 3-year-old human ↗. We might still be better at it, but our theory of mind ability does not make us unique.

the answer? (thus far)

man had always assumed that he was more intelligent than dolphins because he had achieved so much—the wheel, New York, wars and so on—whilst all the dolphins had ever done was muck about in the water having a good time. But conversely, the dolphins had always believed that they were far more intelligent than man—for precisely the same reasons.”

—Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Hitchhiker’s Guide is most well known for asserting that the Answer to the Great Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything is the number forty-two.

The appeal of this claim is its sheer absurdity. Surely a question that complex can’t have such a simple answer!

Very rarely does a book come along and completely change my view of the world. Hitchhiker’s Guide did this for me, albeit within the confines of its fictional universe and classic British humour.

And then there’s Joseph Henrich’s The Secret to Our Success , which does this in real life.

Henrich offers a two-word answer on why humans are so uniquely successful as a species—

cumulative culture

The Secret to Our Success is not a novel. It’s denser than a protein bar, dryer than a dressing-less salad and as close as you can get to being a textbook without actually being one. I took a class ↗ where an entire semester’s worth of lectures were solely devoted to deconstructing this book and its supporting studies. It is among my favorite classes of all time.

Henrich’s argument on collective culture ultimately boils down into the claim that humanity has invented Evolution 2.0. If left to the whims of biological evolution, we’d all be dead— so we enlisted the help of cultural evolution to supercharge our propensity for change.

To be clear, we’re not the only species to have evolved culture. We’ve observed extensively ↗ the evolution of birdsong over time, location, and subpopulations. Birds pass their unique songs from generation to generation; New York birds sing different songs from California birds.

Cultural evolution and genetic evolution are deeply intertwined in our species’ history. As we grew our technologies like fire and shelter-building, we had enough energy to evolve bigger brains. And as our brains grew bigger, we could more easily develop even more complex technology like medicine.

We are the only known species to succumb to this endless cycle of evolution, in becoming wholly dependent on our culture. It’s so pervasive that basically no modern human in an industrialized economy would be able to survive on their own if society were to collapse.

essential prosociality

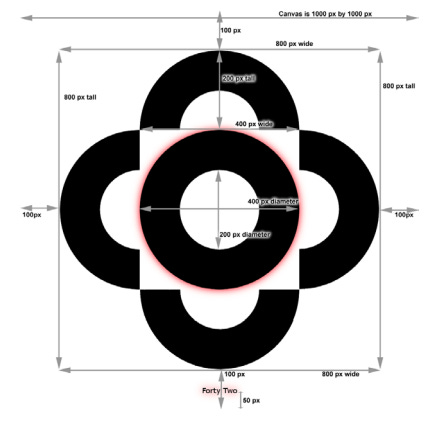

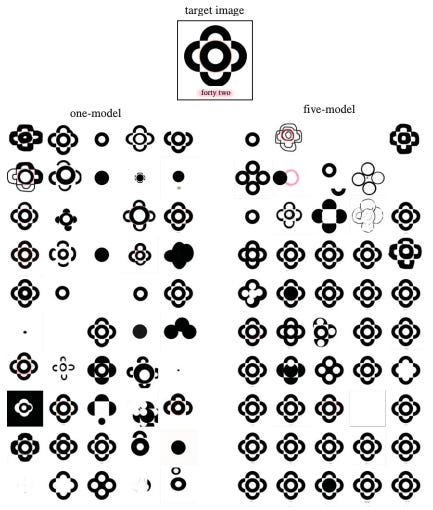

In one experiment (Muthukrishna et al. 2013) ↗, participants learned how to use a complex image editing tool to reproduce the pattern above. They were split into 2 groups of 10 generations.

In one group, each generation had access only to one person’s written instructions from the previous generation. In the other group, everyone had access to instructions from all five participants from the previous generation.

The results were profound.

We’ve created an environment where we have to be as prosocial as possible to survive. We steal as much knowledge from as many people as possible because our greatest skill is to learn together. From generation to generation, our knowledge base grows exponentially while other species stagnate.

Humanity is unique in a lot of ways: we have written language, we’re highly intelligent, we can build fires and computers and space shuttles.

None of this would be possible without cumulative culture, so let’s keep the knowledge flowing. The humans of the future will thank us!

afterword

I’ve always enjoyed the process of synthesis. Gathering a whole bunch of seemingly unrelated things to all come together at once, even if only for a moment, is serendipitous in the truest sense of the word.

College classes often feel siloed, with each professor making a self-contained curriculum based on their own research and perspectives on the world. Sometimes, they stay that way forever and then we have people complaining about how useless their humanities classes are. But when I start mapping the constellations, I can see they’ve changed my life.

I’d like to acknowledge the professors and courses that made this piece possible:

- Philosophy 5: Science and Human Understanding, Shamik Dasgupta

- Anthropology 1: Introduction to Biological Anthropology, Sabrina Agrawal

- Psychology 140: Developmental Psychology, Jan Engelmann

- Psychology 124: The Evolution of Human Behavior, Lucia Jacobs